But then the Court Conductor would give a little speech with big words and say that it was as good as before, and so it was as good as before.

Five years went by and the whole country was greatly saddened because it was said that the emperor was sick and wouldn’t live much longer. The people had been very fond of him, but a new emperor had already been selected. His subjects stood out on the street and asked the chamberlain how the old emperor was doing.

“P!” he said and shook his head.

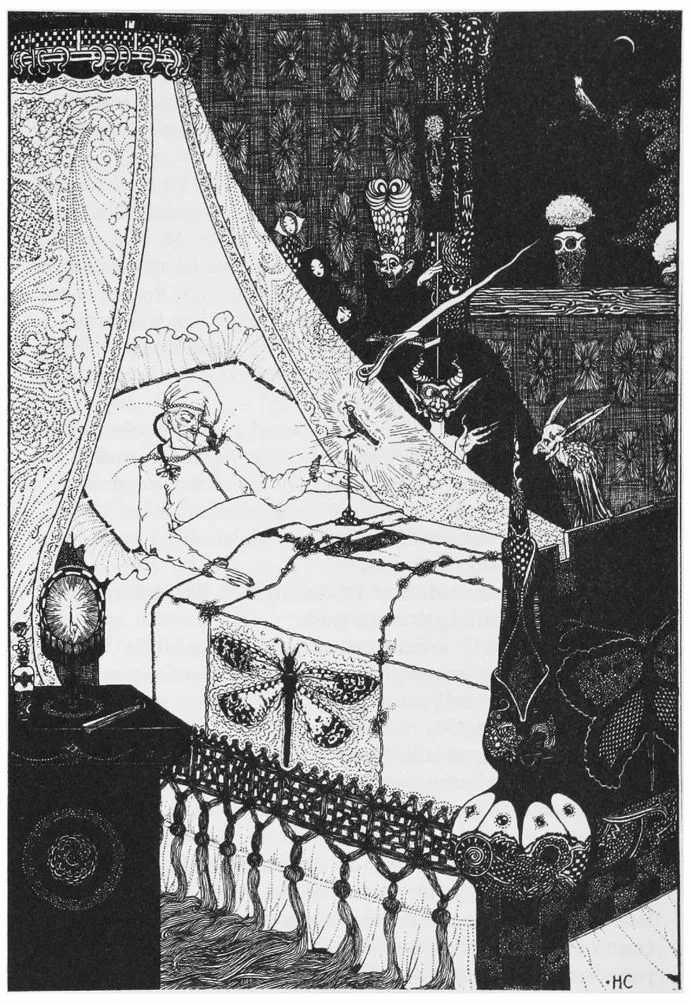

Cold and pale, the emperor lay in his big magnificent bed. The whole court thought he was dead, and all of them ran to greet the new emperor. The chamber attendants ran about to talk about it, and the palace maids had their usual gossip. There were cloth runners spread in all the rooms and hallways so that you couldn’t hear anyone walk, and therefore it was very quiet—so quiet. But the emperor wasn’t dead yet. Stiff and pale, he lay in the magnificent bed with the long velvet curtains and the heavy gold tassels. High on the wall a window was open, and the moonlight shone on the emperor and the artificial bird.

The poor emperor was barely able to draw a breath; it was as if something was sitting on his chest. He opened his eyes, and then he saw that it was Death sitting there. He had put on the emperor’s golden crown and held in one hand his golden sword, and in the other his magnificent banner. Round about in the folds of the velvet bed curtains strange heads were peeping out, some quite terrible and others blessedly mild. They were the emperor’s good and evil deeds looking at him, now that Death was sitting on his heart.

“Do you remember that?” whispered one after the other. “Do you remember that?” and then they spoke to him of so many things that the sweat sprang out on his forehead.

“I knew nothing about that!” said the emperor. “Music, music, the big Chinese drum!” he called, “so that I won’t hear everything that they’re saying.”

But they continued, and Death nodded like a Chinaman along with everything that was said.

“Music, music!” cried the emperor. “You little blessed golden bird. Sing, just sing! I have given you gold and precious things. I have myself hung my golden slipper around your neck. Sing, oh sing!”

But the bird stood still. There was no one to wind it up, and otherwise it didn’t sing, but Death with his big empty eye sockets continued to look at the emperor, and it was quiet, so terribly quiet.

Suddenly outside the window came a beautiful song. It was the little, live nightingale, sitting on the branch outside. It had heard about the emperor’s sorrows and had come to sing with comfort and hope for him, and as it sang, the figures became paler and paler, the blood flowed quicker and quicker in the emperor’s weak limbs, and Death itself listened and said: “Sing on, little nightingale, sing on.”

“Music, music!” cried the emperor.

“You little blessed golden bird. Sing, just sing!”

“Will you give me the magnificent golden sword? Will you give me the precious banner? Will you give me the emperor’s crown?”

And Death gave each treasure for a song, and the nightingale continued to sing. It sang about the quiet churchyard, where the white roses grow, where the elder trees emit their scent, and where the fresh grass is watered by tears of the survivors. Then Death felt a longing for his garden and glided, like a cold, white fog, out the window.

“Thank you, thank you,” said the emperor. “You heavenly little bird, I know you well. I chased you away from my country and my empire, and yet your song has cast away the evil sights from my bed and taken Death from my heart! How shall I reward you?”

“You have rewarded me,” said the nightingale. “I received tears from your eyes the first time I sang for you, and I’ll never forget that. Those are the jewels that enrich a singer’s heart. But rest now and become healthy and strong.

1 comment