Incidentally, though no one can be certain about what Elizabethan English sounded like, specialists tend to believe it was rather like the speech of a modern stage Irishman (time apparently was pronounced toime, old pronounced awld, day pronounced die, andjoin pronounced jine) and not at all like the Oxford speech that most of us think it was.

An awareness of the difference between our pronunciation and Shakespeare’s is crucial in three areas—in accent, or number of syllables (many metrically regular lines may look irregular to us); in rhymes (which may not look like rhymes); and in puns (which may not look like puns). Examples will be useful. Some words that were at least on occasion stressed differently from today are aspect, complete, forlorn, revenue, and sepùlcher. Words that sometimes had an additional syllable are emp[e]ress, Hen[e]ry, mon[e]th, and villain (three syllables, vil-lay-in). An additional syllable is often found in possessives, like moon’s (pronounced moones) and in words ending in -tion or -sion. Words that had one less syllable than they now have are needle (pronounced neel) and violet (pronounced vilet). Among rhymes now lost are one with loan, love with prove, beast with jest, eat with great. (In reading, trust your sense of metrics and your ear, more than your eye.) An example of a pun that has become obliterated by a change in pronunciation is Falstaff’s reply to Prince Hal’s “Come, tell us your reason” in I Henry IV. “Give you a reason on compulsion? If reasons were as plentiful as blackberries, I would give no man a reason upon compulsion, I” (2.4.237-40). The ea in reason was pronounced rather like a long a, like the ai in raisin,.hence the comparison with blackberries.

Puns are not merely attempts to be funny; like metaphors they often involve bringing into a meaningful relationship areas of experience normally seen as remote. In 2 Henry IV, when Feeble is conscripted, he stoically says, “I care not. A man can die but once. We owe God a death” (3.2.242-43), punning on debt, which was the way death was pronounced. Here an enormously significant fact of life is put into simple commercial imagery, suggesting its commonplace quality. Shakespeare used the same pun earlier in 1 Henry IV, when Prince Hal says to Falstaff, “Why, thou owest God a death,” and Falstaff replies, “‘Tis not due yet: I would be loath to pay him before his day. What need I be so forward with him that calls not on me?” (5.1.126-29).

Sometimes the puns reveal a delightful playfulness; sometimes they reveal aggressiveness, as when, replying to Claudius’s “But now, my cousin Hamlet, and my son,” Hamlet says, “A little more than kin, and less than kind!” ( 1.2.64-65). These are Hamlet’s first words in the play, and we already hear him warring verbally against Claudius. Hamlet’s “less than kind” probably means (1) Hamlet is not of Claudius’s family or nature, kind having the sense it still has in our word mankind; (2) Hamlet-is not kindly (affectionately) disposed toward Claudius; (3) Claudius is not naturally (but rather unnaturally, in a legal sense incestuously) Hamlet’s father. The puns evidently were not put in as sops to the groundlings; they are an important way of communicating a complex meaning.

2. Vocabulary. A conspicuous difficulty in reading Shakespeare is rooted in the fact that some of his words are no longer in common use—for example, words concerned with armor, astrology, clothing, coinage, hawking, horsemanship, law, medicine, sailing, and war. Shakespeare had a large vocabulary—something near thirty thousand words—but it was not so much a vocabulary of big words as a vocabulary drawn from a wide range of life, and it is partly his ability to call upon a great body of concrete language that gives his plays the sense of being in close contact with life. When the right word did not already exist, he made it up. Among words thought to be his coinages are accommodation, all-knowing, amazement, bare-faced, countless, dexterously, dislocate, dwindle, fancy-free, frugal, indistinguishable, lackluster, laughable, overawe, premeditated, sea change, star-crossed. Among those that have not survived are the verb convive, meaning to feast together, and smilet, a little smile.

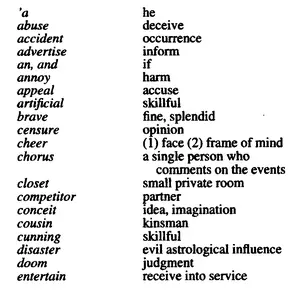

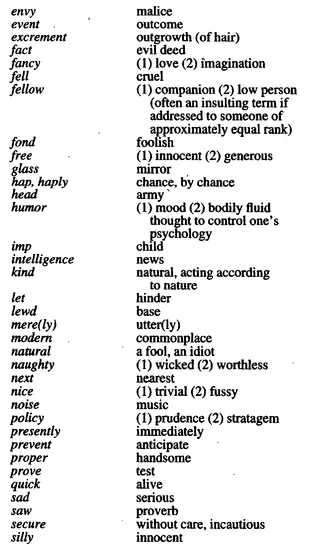

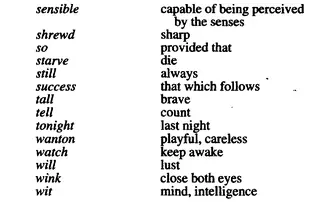

Less overtly troublesome than the technical words but more treacherous are the words that seem readily intelligible to us but whose Elizabethan meanings differ from their modern ones. When Horatio describes the Ghost as an “erring spirit,” he is saying not that the ghost has sinned or made an error but that it is wandering. Here is a short list of some of the most common words in Shakespeare’s plays that often (but not always) have a meaning other than their most usual modern meaning:

All glosses, of course, are mere approximations; sometimes one of Shakespeare’s words may hover between an older meaning and a modem one, and as we have seen, his words often have multiple meanings.

3. Grammar. A few matters of grammar may be surveyed, though it should be noted at the outset that Shakespeare sometimes made up his own grammar. As E.A. Abbott says in A Shakespearian Grammar, “Almost any part of speech can be used as any other part of speech”: a noun as a verb (“he childed as I fathered”); a verb as a noun (“She hath made compare”); or an adverb as an adjective (“a seldom pleasure”). There are hundreds, perhaps thousands, of such instances in the plays, many of which at first glance would not seem at all irregular and would trouble only a pedant. Here are a few broad matters.

Nouns: The Elizabethans thought the -s genitive ending for nouns (as in man’s) derived from his; thus the line “ ‘gainst the count his galleys I did some service,” for “the count’s galleys.”

Adjectives: By Shakespeare’s time adjectives had lost the endings that once indicated gender, number, and case. About the only difference between Shakespeare’s adjectives and ours is the use of the now redundant more or most with the comparative (“some more fitter place”) or superlative (“This was the most unkindest cut of all”). Like double comparatives and double superlatives, double negatives were acceptable; Mercutio “will not budge for no man’s pleasure.”

Pronouns: The greatest change was in pronouns. In Middle English thou, thy, and thee were used among familiars and in speaking to children and inferiors; ye, your, and you were used in speaking to superiors (servants to masters, nobles to the king) or to equals with whom the speaker was not familiar. Increasingly the “polite” forms were used in all direct address, regardless of rank, and the accusative you displaced the nominative ye. Shakespeare sometimes uses ye instead of you, but even in Shakespeare’s day ye was archaic, and it occurs mostly in rhetorical appeals.

Thou, thy, and thee were not completely displaced, however, and Shakespeare occasionally makes significant use of them, sometimes to connote familiarity or intimacy and sometimes to connote contempt. In Twelfth Night Sir Toby advises Sir Andrew to insult Cesario by addressing him as thou: “If thou thou‘st him some thrice, it shall not be amiss” (3.2.46-47).

1 comment