It is a scene out of Bosch. Every female teenager in Britain is having her own teenage crisis, simultaneously as one, right now, vaguely in time to our music. The frenzy is contagious. We are the catalyst for their explosions, one by one, by the thousands.

We have become idols, icons. Subjects of worship.

PART 1

ANALOG YOUTH

1 Hey Jude

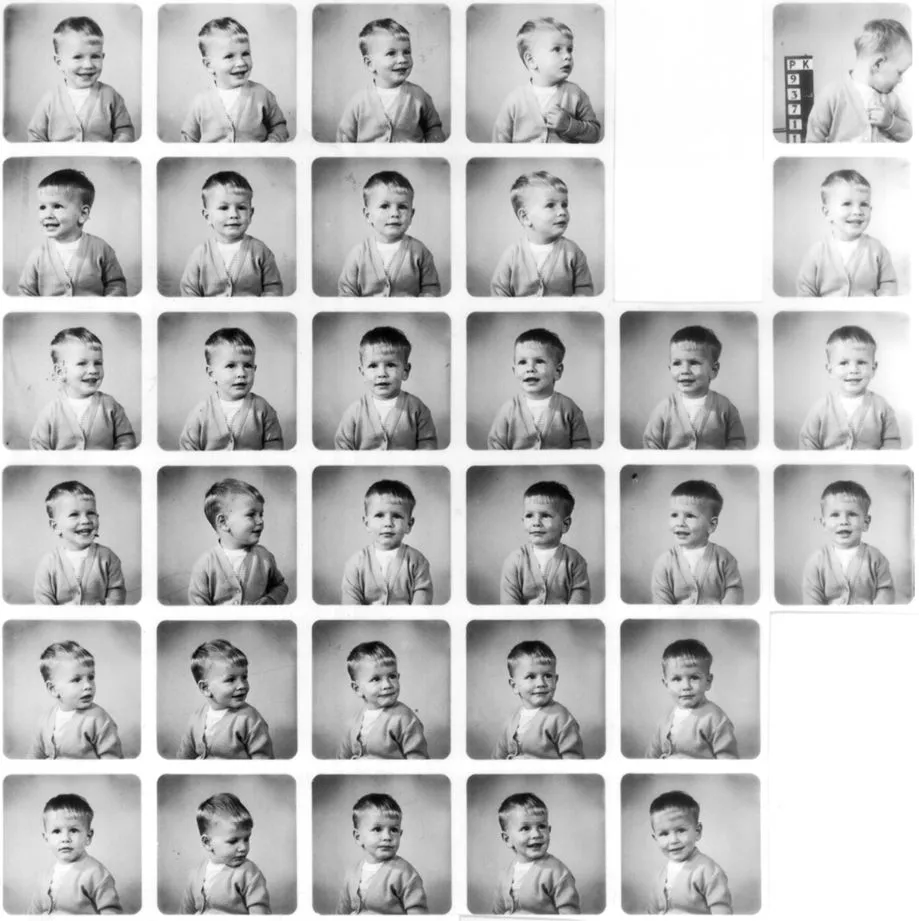

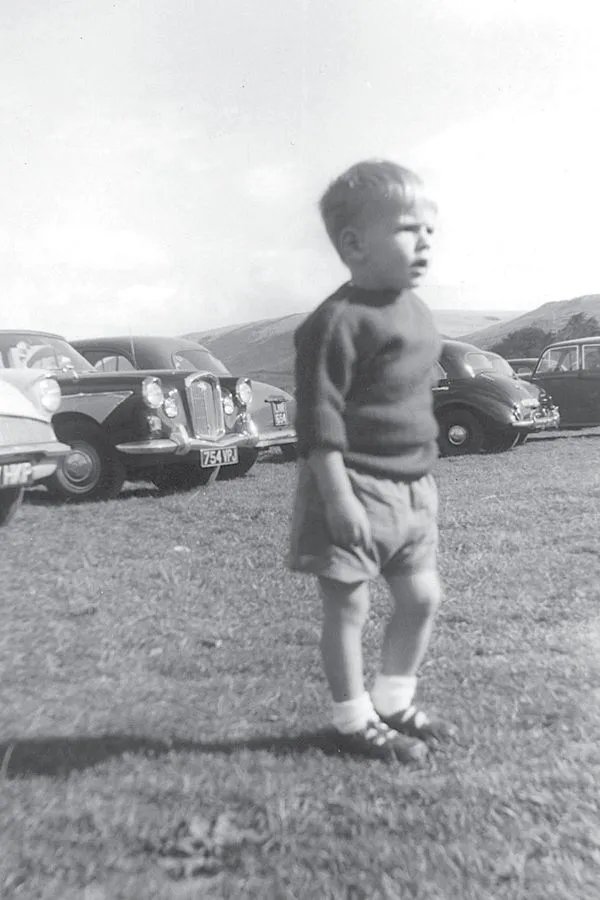

I am four years old. Confident and shy. Hair blonder than it would be in my teen years. In shorts and sandals, a young prince of the neighborhood, the south Birmingham suburb of Hollywood. How perfect.

Ten o’clock in the morning on any given weekday in 1964, and I have stepped down off the porch and wait, kicking at the grooved concrete driveway, watching as Mom pulls the front door closed, locks it up, and puts the key in her handbag; she puts the handbag in the shopping bag, and off we go. Left off the drive and up the hill that is the street on which we live, Simon Road. Our house is number 34, one up from where the road ends.

We walk together along the pavement, counting down: 32, 30, 28. On the left side of the street are all the even-numbered semidetached houses, single buildings designed to function as two separate homes (ours is twinned with number 36). Across the street, the odd-numbered houses are detached, each building a single dwelling, all much larger than ours, and so are the back gardens, which are long and tree-filled and bordered at the bottom by a stream. The driveways are slicker too, with space for more than one car.

Later on, when I started to become a little status-aware, I would ask my parents, “Why didn’t you pay the extra six hundred quid that would have got us a stream at the back?”

I hold Mom’s hand, remembering the Beatles song that is so often on the radio, as the incline gets steeper. We reach the crest of the hill, where Simon Road meets Douglas Road, and turn right.

We pass a twelve-foot-high holly bush, the only evidence I have found that suggests where the estate got its name. We march on, crossing Hollywood Lane in front of Gay Hill Golf Club, an establishment that will assume mythical proportions in my imagination as a venue for wife-swapping parties, not that anyone in my family ever set foot in the place. There was no truth in the rumor.

Cars flash by, at twenty or even thirty miles an hour. We make it to Highter’s Heath Lane, another main artery of the neighborhood, which must be taken if you’re visiting the old Birmingham of grans and aunts and uncles, recreational parks and bowling greens. It gets traversed a lot by the Taylor family at weekends. It must also be used by mother and son if we are to reach our destination today—St. Jude’s parish church.

All this walking. We’ve been doing it together for as long as I can remember. Mom doesn’t drive and never will. At first, I’d be in my pushchair, but now that I’m old enough, we walk side by side, which must have come as a relief to Mom. There’s no complaining from me, it just is and ever shall be. Amen.

She’s sweating now in her woolen skirt and raincoat, keen to get there. We walk past the Esso filling station where, in 1970, I will complete my set of commemorative soccer World Cup coins. One last left turn and we are on the paved forecourt, upon which sits, in breeze-block splendor, St. Jude’s parish church.

I would go to many beautiful, awe-inspiring churches when I was older—St. Patrick’s on Fifth Avenue, St.

1 comment