Peter’s in Rome, Notre-Dame de Paris—but St. Jude’s on Glenavon Road was the most pragmatic people’s church anywhere in the First World. Built in the post–World War II years, St. Jude’s was intended as a temporary structure, not meant to last more than a few years. It’s coming up on twenty now and yawning with cold air and aching joints. Single story, with windows every six feet along its length, and a roof of corrugated iron.

Its crude purity enhanced the idea the St. Jude’s faithful had about being the chosen ones. Why else would we gather together in this cold, ugly place unless it was an absolute certainty that we would benefit from it?

Father Cassidy’s great fund-raising scheme of the seventies eventually resulted in a new St. Jude’s church. This was no small achievement. None of the congregants could be considered rich or even well-off. Everyone had to count their pennies. Getting the money to build a new church from his parishioners took a great deal of persuading.

Fortunately, he had God on his side.

A communal sense of readiness sends us through the small lobby where, on raw wooden tables, literature is offered; some for sale, some for free. Textbooks, Bibles, songbooks, and other merchandise, including rosaries, crucifixes, and pendants of St. Jude (the patron saint of hopeless cases, really).

On into the nave, where there is a smell of sweat and yesterday’s incense. It’s usually cool in here, sometimes warm but never hot. A tall redheaded man plays a rickety-looking organ, quietly piping sweet music that is barely there. Eno would call it ambient. Candles burn lazily with a holy scent.

On the strike of eleven the service begins. The priest enters smartly, followed by a pair of young men in white robes—the priest’s team, his posse—one of whom swings a silver chalice from which more incense issues. The air in the church needs a good cleansing before the good father can breathe it.

He wears elaborate clothing, a robe of green-and-gold silk with a red cross on his back. Beneath the cloak, ankle-length turned-up trousers reveal the black socks and black brogues of any other working man.

The music surges in volume and we all stand. The red-haired man leads us in a song we know well, “The Lord Is My Shepherd.” I open the hymnal to read the words. I like this one but, like Mom, I’m too embarrassed to sing out loud. I wish I could; I just don’t, but I like the feeling of togetherness that comes from everyone in the room singing the same words.

Once the song is over, the priest walks to the dais. He glances down at his Bible, opens his hands wide, and says, “Let us pray.”

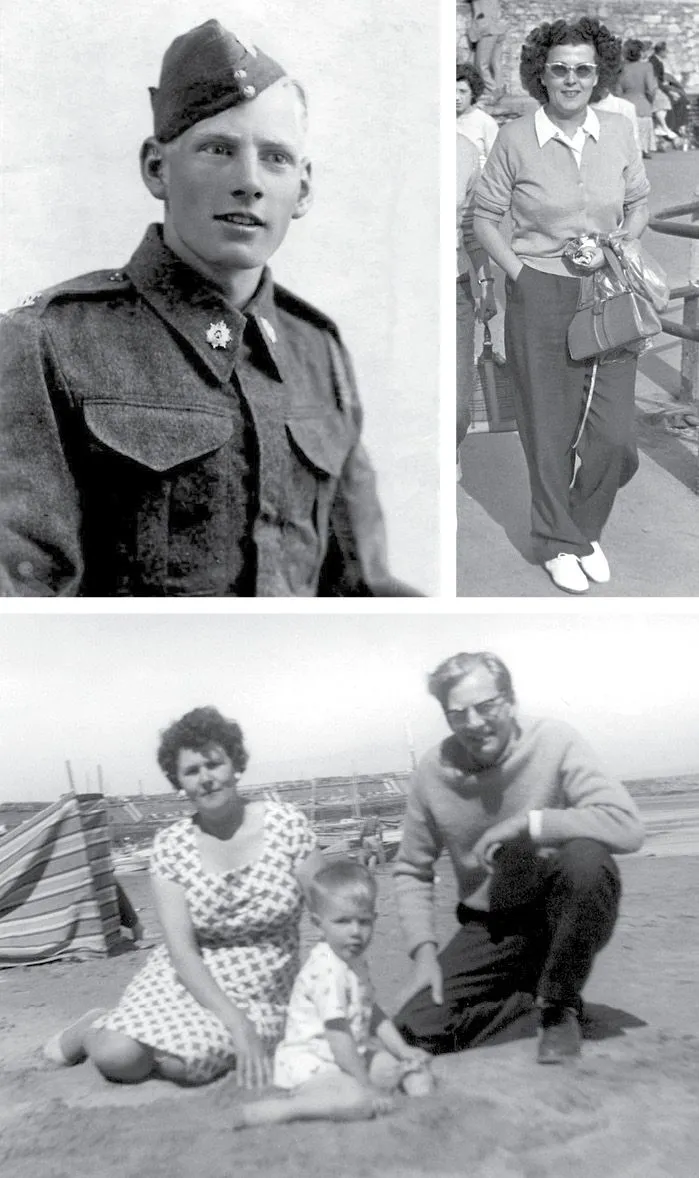

2 Jack, Jean, and Nigel

Church just was. Like electricity, heat, or black-and-white TV—something that just existed. I assumed everyone went five times a week. I didn’t know I was one of a subset, a species. A Roman Catholic.

You don’t question things like that when you’re little.

1 comment