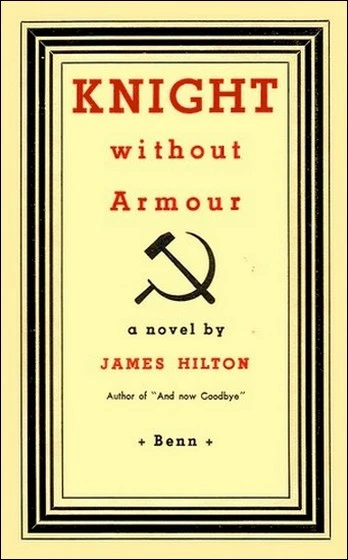

Knight Without Armour

JAMES HILTON

KNIGHT WITHOUT ARMOUR

First published by Ernest Benn Ltd., London, 1933

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

Part V

PROLOGUE

“There died on the 13th inst. at Roone’s Hotel,

Carrigole, Co. Cork, where he had been staying for some time, Mr. Ainsley

Jergwin Fothergill, in his forty-ninth year. Mr. Fothergill was the youngest

son of the Reverend Wilson Fothergill, of Timperleigh, Leicestershire.

Educated at Barrowhurst and at St. John’s College, Cambridge, he was

for a time a journalist in London before seeking his fortune abroad. Since

1920 he had been closely associated with the plantation rubber industry, and

was the author of a standard work upon that subject.”

So proclaimed the obituary column of The Times on the morning of

October 19th, 1929. But The Times gets to Roone’s a day and a

half late, and Fothergill was already beneath the soil of Carrigole

churchyard by then. There had been some slight commotion over the burial; an

English priest had wired at the last moment that the man was a Catholic. This

seemed strange, for he had never been noticed to go to Mass; but still, there

was the telegram, and since most Carrigole folk were buried as Catholics

anyway, the matter was not difficult to arrange.

There was also an inquest. Fothergill had apparently died in his sleep;

one of the maids took up his cup of tea in the morning and actually left it

on his bedside table without knowing he was dead. She told the district

coroner she had said—“Here’s your tea, sir,” and that

she thought he had smiled in answer. Nobody found out the truth till nearly

noon. Then a doctor who happened to be staying at the hotel saw the body and

said it must have been lifeless for at least ten hours.

Just in time for the inquest a London doctor arrived to testify that

Fothergill had consulted him some weeks before about a heart complaint. It

was the sort of thing that might finish off anyone quite suddenly, so of

course all was clear, on the evidence, and the verdict ’Death from

natural causes’ came in with record speed.

The whole affair provided an acute though temporary sensation at

Roone’s Hotel, which, though the season was almost over, chanced to be

fairly full at the time owing to a cruiser in harbour. Roone himself was

rather peeved; he was just beginning to work up his place after the many

years of ‘trouble,’ and it certainly did him no good to have

guests dying on him in such a way. He was especially annoyed because it had

all got into the Dublin and London papers—that, of course, being due to

Halloran, Carrigole’s too ambitious journalist, who would (Roone said)

sell his best friend’s reputation for half a guinea.

As for the dead man, Roone could only shrug his shoulders. Rather crossly

he told the occupants of his crowded private bar how little he knew about the

fellow. Never set eyes on him till the September, when he had arrived from

Killarney one evening with a small suitcase. Evidently hadn’t meant to

stop long, and at the end of a week had sent to London for more luggage. Very

quiet sort, civil and all that, but somehow not the kind of chap a fellow

would naturally take to…Yes, practically teetotal, too—nearly as bad

for business as the Cook’s people who came loaded with coupons for all

they took and drank nothing but water. “Although, by the way,”

Roone added, “he did come in here for a nightcap the evening

before—I remember serving him.”

“Yes, I remember too,” put in a plus-foured youth. “I

made some casual remark to him about something or other just to be polite,

that was all—but he hardly answered me. Rather surly, I thought at the

time.”

At which Mrs. Roone intervened, tartly: “Of course it was easy to

see what he was stopping on here for, and more shame to him, I

say.”

Everyone in the bar nodded, for everyone had been waiting for that matter

to be mentioned. There had been an American girl staying at the hotel with

her mother; the two had been the only guests with whom the dead man had

struck up any sort of acquaintance. He had gone for drives and picnics with

them; he had taken his meals at their table; he had sometimes danced with the

girl in the evenings. He was after her, Mrs.

1 comment