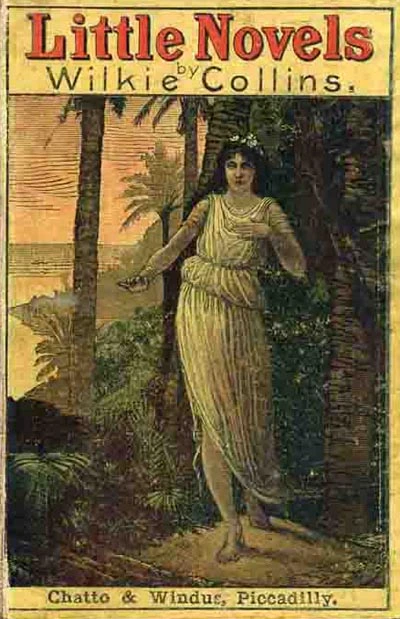

Little Novels

LITTLE NOVELS

by Wilkie Collins

MRS. ZANT AND THE GHOST.

I.

THE course of this narrative describes the return of a

disembodied spirit to earth, and leads the reader on new and

strange ground.

Not in the obscurity of midnight, but in the searching light of

day, did the supernatural influence assert itself. Neither revealed

by a vision, nor announced by a voice, it reached mortal knowledge

through the sense which is least easily self-deceived: the sense

that feels.

The record of this event will of necessity produce conflicting

impressions. It will raise, in some minds, the doubt which reason

asserts; it will invigorate, in other minds, the hope which faith

justifies; and it will leave the terrible question of the destinies

of man, where centuries of vain investigation have left it--in the

dark.

Having only undertaken in the present narrative to lead the way

along a succession of events, the writer declines to follow modern

examples by thrusting himself and his opinions on the public view.

He returns to the shadow from which he has emerged, and leaves the

opposing forces of incredulity and belief to fight the old battle

over again, on the old ground.

II.

THE events happened soon after the first thirty years of the

present century had come to an end.

On a fine morning, early in the month of April, a gentleman of

middle age (named Rayburn) took his little daughter Lucy out for a

walk in the woodland pleasure-ground of Western London, called

Kensington Gardens.

The few friends whom he possessed reported of Mr. Rayburn (not

unkindly) that he was a reserved and solitary man. He might have

been more accurately described as a widower devoted to his only

surviving child. Although he was not more than forty years of age,

the one pleasure which made life enjoyable to Lucy's father was

offered by Lucy herself.

Playing with her ball, the child ran on to the southern limit of

the Gardens, at that part of it which still remains nearest to the

old Palace of Kensington. Observing close at hand one of those

spacious covered seats, called in England "alcoves," Mr.

Rayburn was reminded that he had the morning's newspaper in his

pocket, and that he might do well to rest and read. At that early

hour the place was a solitude.

"Go on playing, my dear," he said; "but take care

to keep where I can see you."

Lucy tossed up her ball; and Lucy's father opened his

newspaper. He had not been reading for more than ten minutes, when

he felt a familiar little hand laid on his knee.

"Tired of playing?" he inquired--with his eyes still

on the newspaper.

"I'm frightened, papa."

He looked up directly. The child's pale face startled him.

He took her on his knee and kissed her.

"You oughtn't to be frightened, Lucy, when I am with

you," he said, gently. "What is it?" He looked out

of the alcove as he spoke, and saw a little dog among the trees.

"Is it the dog?" he asked.

Lucy answered:

"It's not the dog--it's the lady."

The lady was not visible from the alcove.

"Has she said anything to you?" Mr. Rayburn

inquired.

"No."

"What has she done to frighten you?"

The child put her arms round her father's neck.

"Whisper, papa," she said; "I'm afraid of her

hearing us. I think she's mad."

"Why do you think so, Lucy?"

"She came near to me. I thought she was going to say

something. She seemed to be ill."

"Well? And what then?"

"She looked at me."

There, Lucy found herself at a loss how to express what she had

to say next--and took refuge in silence.

"Nothing very wonderful, so far," her father

suggested.

"Yes, papa--but she didn't seem to see me when she

looked."

"Well, and what happened then?"

"The lady was frightened--and that frightened me. I

think," the child repeated positively, "she's

mad."

It occurred to Mr. Rayburn that the lady might be blind. He rose

at once to set the doubt at rest.

"Wait here," he said, "and I'll come back to

you."

But Lucy clung to him with both hands; Lucy declared that she

was afraid to be by herself. They left the alcove together.

The new point of view at once revealed the stranger, leaning

against the trunk of a tree. She was dressed in the deep mourning

of a widow. The pallor of her face, the glassy stare in her eyes,

more than accounted for the child's terror--it excused the

alarming conclusion at which she had arrived.

"Go nearer to her," Lucy whispered.

They advanced a few steps. It was now easy to see that the lady

was young, and wasted by illness--but (arriving at a doubtful

conclusion perhaps under the present circumstances) apparently

possessed of rare personal attractions in happier days. As the

father and daughter advanced a little, she discovered them. After

some hesitation, she left the tree; approached with an evident

intention of speaking; and suddenly paused. A change to

astonishment and fear animated her vacant eyes. If it had not been

plain before, it was now beyond all doubt that she was not a poor

blind creature, deserted and helpless. At the same time, the

expression of her face was not easy to understand. She could hardly

have looked more amazed and bewildered, if the two strangers who

were observing her had suddenly vanished from the place in which

they stood.

Mr. Rayburn spoke to her with the utmost kindness of voice and

manner.

"I am afraid you are not well," he said.

1 comment