Mansfield with Monsters

Introduction

Born in 1888, Katherine Mansfield is one of New Zealand’s most famous and influential writers. Much is known of her short life through her writing, her letters, and the correspondence and recollections of her family, loved ones, and peers. Her modernist stories are striking and ground-breaking. With so much public discourse already extant, is there really more to learn about Mansfield?

Literary historian Dr Marcus Walker believes there is. His doctoral thesis of 1999, Mansfield and the Occult: the untold story, asserts that her participation in rites conducted by the Ordo Temple Orientis under the leadership of Aleister Crowley, as well as her intimate connection with the noted psychic Florence Cooke, were systematically covered up through the destruction of letters and the intimidation of fellow participants. Walker believes that Mansfield’s obsession with the artefacts brought to London by Carter’s Egypt expeditions was deliberately omitted from official biographies, and the rumour that she spent a night in the sarcophagus of the emperor Tutankhamun has always been considered apocryphal, yet Walker’s research hints at some underlying truth to the tale. It is a matter of record that Mansfield, accompanied by her loyal companion Ida Baker, travelled extensively to sanatoriums and spas for her health. That one of these trips was a cover story for an expedition into the Himalayas in search of the elusive yeti is perhaps one of Walker’s less well-supported claims, but it cannot be denied that he uncovered a wealth of new material in his studies, material upon whose authenticity he has staked his reputation.

Following on from the investigative work conducted by Dr Walker, several previously unpublished fragments and early drafts of Mansfield’s stories have come to light. The most detailed of these, a collection of pages torn from Mansfield’s journals, were discovered by Walker in a Buddhist monastery in Shigatse, Tibet. Through a close study of these fragments it has been possible to gain an insight into a previously unknown facet of Mansfield’s personality—her obsession with the monstrous. The everyday horror of life is infused into her published work, along with a melancholic sense of revelation and frail beauty. Missing from the body of writing published to date is any mention of the more physical, mythical creatures she believed had once populated the Earth. A secret diary kept by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle mentions a rendezvous with Mansfield, during which she was “utterly delighted by the faeries” of the famous Cottingley garden. Whether Mansfield was involved in the wider religious activities of Conan Doyle’s circle is not known, nor is the full extent of her involvement with the writer Howard Phillips Lovecraft, whose early works were particular favourites of the young Mansfield.

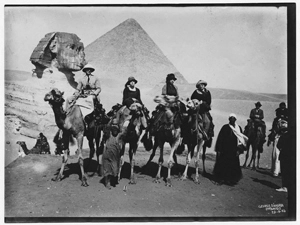

“Pyramids”. D’Andria, George—Photographer. 1924. Dr Walker believes that the woman on the second camel from the right is Katherine Mansfield. The New York Public Library. Photography Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs.

This volume of revised stories is in part speculation, in part careful reconstruction of those stories that originally contained the horrors that Mansfield most feared. It is impossible to say whether she truly believed her world to contain such creatures, to know whether she had in fact seen things which shook the scales from her eyes, but as Dr Ian Conrich of the University of Essex has written, she was “drawn to the horrors of life”. Those closest to her have taken her secrets to the grave, and many went to great lengths to help conceal her unusual beliefs. The feeling that Mansfield’s spirit returned after her death and was with her friends and family as they moved on and reconstructed a more publicly acceptable version of her life was shared by many of her closest friends and loved ones, and is a matter of record. Assertions have been made that Mansfield’s spirit possessed the body of her husband John Murray’s second wife, Violet, and that Mansfield’s ghost had an influence on those who loved her long after her death. There has even been speculation about the real reason for Mansfield’s body being exhumed, with some doubting the claim that it was merely relocated to a pauper’s grave.

Carl H. Sederholm, associate professor in humanities, classics, and comparative literature at Brigham Young University in Utah, writes:

We’ve always known that Modernist literature was rife with allusions to the horrific, the occult, and the monstrous (consider, for instance, the Frankensteinesque horrors implied by T. S. Eliot’s “patient etherized upon a table,” Gertrude Stein’s obsession with the broken undead bodies of Cubism, or Hemingway’s anxiety over being drained of his rugged life-force). Genteel manners and the concern for a high-standing literary reputation, however, steered writers and publishers away from explicitly developing these interests, leaving readers with only the slightest hint of what was lurking beneath the surface—surely nothing less than a Freudian nightmare, an uncanny return of the cruelly repressed. With the publication of this book, we must now reconsider the ways Katherine Mansfield’s own monumental modernism is nothing less than a significant breeding ground for the development of the truly weird and the frightfully monstrous.

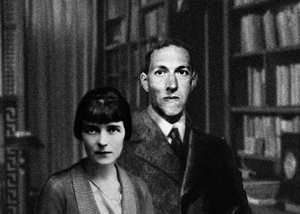

Katherine Mansfield with American author H.

1 comment