Pagett, M.D.

Mr.… [Cyriack] Skinner, who was his disciple.

John Dryden, Esq., Poet Laureate, who very much admires him, and went to him to have leave to put his Paradise Lost into a drama in rhyme. Mr. Milton received him civilly, and told him he would give him leave to tag his verses.18

His widow assures me that Mr. T. Hobbes was not one of his acquaintance, that her husband did not like him at all, but he would acknowledge him to be a man of great parts, and a learned man. Their interests and tenets did run counter to each other, vide Mr. Hobbes’ Behemoth.

“Anno Domini 1619, he was ten years old, as by his picture; and was then a poet.” (Illustration Credit fm1.)

1. Oriana: Milton’s father contributed a song, “Fair Orian,” to The Triumphs of Oriana (1601), a volume of songs dedicated to Queen Elizabeth I.

2. die Veneris: Venus’s Day, i.e., Friday.

3. I.e., Nathaniel Tovey.

4. I.e., Forest Hill.

5. Triplechord about divorce: most likely Tetrachordon (four strings).

6. Vidua affirmat: His widow maintains.

7. John Speed: author of The History of Great Britain, he is buried in St. Giles, as is John Foxe, author of The Book of Martyrs and Acts and Monuments.

8. 1 Amores 5.18: “There was not a blemish on her body.”

9. manna: a mild laxative.

10. littera canina: dog letter, so called because making a continuous r sound resembles a dog’s growl when threatening attack.

11. A note to himself.

12. Scil.… manè: It is well known (scilicet) … in the morning.

13. I.e., Milton composed his epic between 1658 and 1663.

14. Milton published his Second Defense of the English People (1654), with its attack on More as the author of the Cry of the King’s Blood (Regii Sanguinis Clamor), even after learning that another had written the book.

15. “It is incredible how much the dignity of his style and his most excellent diction have affected all of us.”

16.  : loftiness, altitude.

: loftiness, altitude.

17. We omit here a catalog of Milton’s works.

18. tag his verses: the ends of laces hanging from clothing could be “tagged,” or fitted with metal ornaments. Tagging is here a metaphor for placing rhyming words at the ends of poetic lines, as Dryden did when he transformed the blank verse of Paradise Lost (1667) into the heroic couplets of his opera The State of Innocence (composed 1674; published 1677).

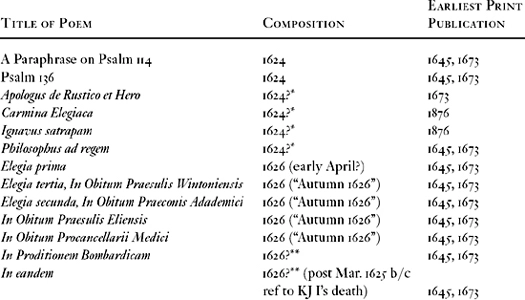

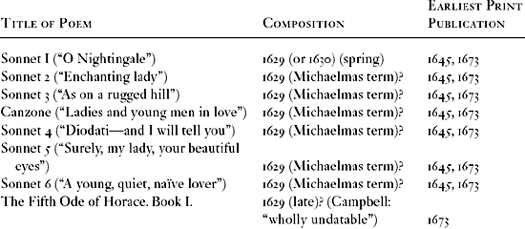

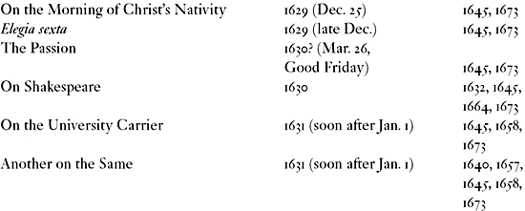

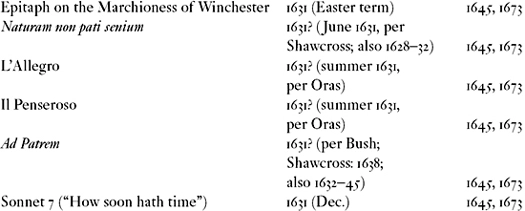

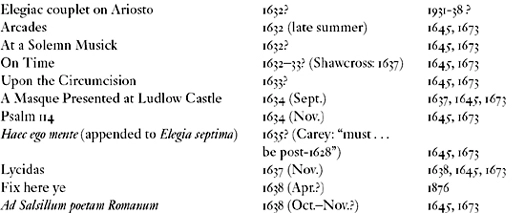

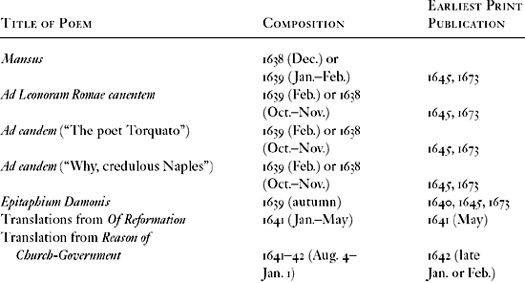

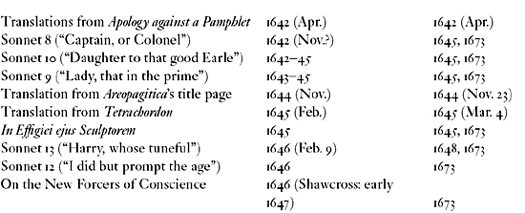

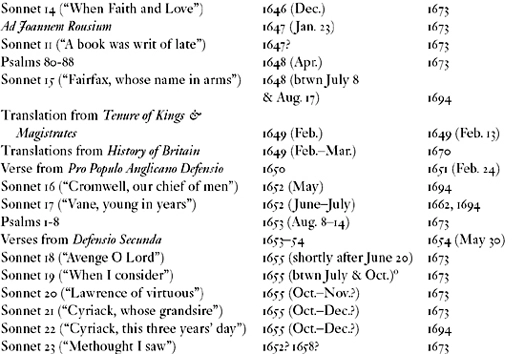

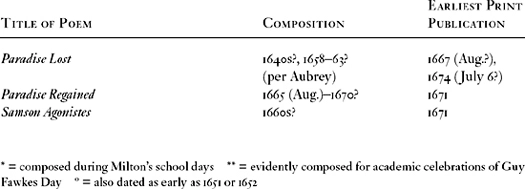

A CHRONOLOGY OF MILTON’S POETRY

Click here to download a PDF of this Chronology.

(Illustration Credit fm3.)

A NOTE ON THE TEXT

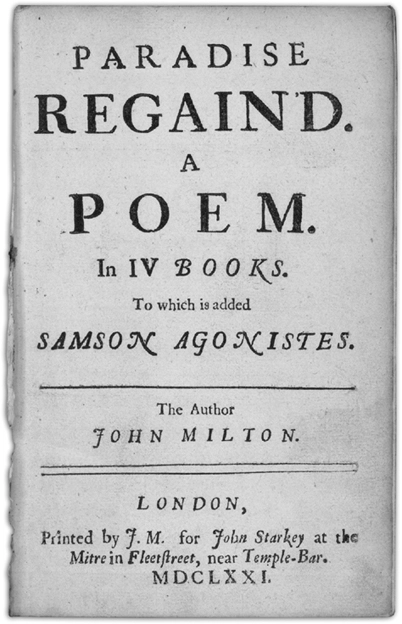

Paradise Regained and Samson Agonistes were first printed in tandem. Although the book was licensed on July 2, 1670, and entered into the Stationers’ Register on September 10, 1670, all known copies bear the date 1671. The book, postdated, was probably issued in 1670 (Knoppers xcviii–xcviv, 1). Its publication occurred about midway between the first edition (1667) and the second edition (1674) of Paradise Lost. The back of this haphazardly printed volume contains a list of errata for each poem and ten lines omitted (whether a late revision or a printing error, we have no way of knowing) from Samson Agonistes.

Both poems appear on the title page, but whereas one is a bit oversold, the other is distinctly undersold. Paradise Regained was the featured attraction, set in large letters at the top of the title page. The name of the brief epic, whatever else Milton may have had in mind, encouraged browsers in London bookstalls to believe, somewhat misleadingly, that this new work was a sequel to Paradise Lost. Samson Agonistes, set in smaller print at the bottom of the title page, is introduced a line earlier by the words “To which is added.” The title page’s treatment of Samson seems to a modern reader breathtakingly casual: this has to rank among the most consequential afterthoughts in English publishing.

Since there are no surviving manuscripts of Paradise Regained or Samson Agonistes, our text for these two poems derives primarily from their first edition. All subsequent printings took place after Milton’s death in 1674. The second edition of 1680 introduced numerous variants, most of which reappeared in the third edition of 1688. It is a measure of the unreliability of the second and third editions that neither corrected the errors listed at the end of the first. In fact, the texts of Paradise Regained and Samson Agonistes were not emended in the manner specified by the 1671 printing until the variorum of Thomas Newton (1752; reissued 1753). The two poems continued to be published together in early editions, and the tradition persists to this day, as our own volume attests. Controversies about dating the composition of the works, especially the vexed case of Samson Agonistes, are discussed in our headnotes.

Texts for the main body of Milton’s shorter poems, including those in Italian, Latin, and Greek, are based on Poems of Mr. John Milton (1645) and the revised and enlarged second edition of this book in 1673. We have also consulted the holograph drafts and transcriptions of those shorter poems found in the Cambridge Manuscript (also called the Trinity Manuscript). Unique problems with the texts of A Masque and “Lycidas” are considered in the headnotes to those works. In general, we have drawn on clarifying moments in the early printed versions and the manuscripts, when they exist, without feeling bound to the old editorial idea of a singular “copy text.” The virtues of an eclectic approach to editing Milton have been ably set forth by John Creaser (1983, 1984).

Milton’s shorter poems are organized in a manner unique to this edition. Numerous editors have tried to retain the order in which these poems appeared in Milton’s 1645 Poems, finding a way to tip in works that first appeared in his 1673 Poems, translations found in his prose works, or pieces never published during his lifetime but discovered subsequently by scholars. Others try to present all the minor poems in their probable order of composition. The result in both cases is chaotic to the modern eye. Poems in different languages jostle against each other.

1 comment