And, in Granada, the capital of Lorca's

Andalusia, a china is a small stone used in paving streets. Context

left us with the most obvious, the Chinese man (or Chinaman,

with all the negative connotations the word carries from Spanish

into English), but the other meanings were important in our thinking because they were meanings we knew Lorca knew.

In collaborating, we also found it critical not only to check

each other for accuracy but for liberty-when one of its chose to

experiment with Lorca, to go over the top, as it were, usually when

it seemed there was no other alternative, the other was there to

question the experiment. Was this really Lorca? Was this beyond

meaning and new interpretation? If interpretation, was it legitimate and necessary interpretation? The presence of the collaborator thus gave its each greater confidence to experiment, to play;

in fact, to discover different, and often better ways to write Lorca

into English.

This last part of our working method also made it clear how

important being poets ourselves was to this particular task of translation. Moving through drafts, thinking out questions of Lorca and

his project, led us to secondary and significant ways to solve translation issues. After wondering what Lorca was trying to do, the later

phases of our work continued to have the wondering of translators but it added the wondering of poets. For both of us a new and

useful question became not simply what was Lorca doing but what

would each of us, as a poet, do? How would we address the poetic

problems Lorca presented? This part of the collaboration left both

of us feeling some trepidation because it meant that the Medina/

Statman collaboration had become the making finally of something that Lorca did not actually write. Doing this we found ourselves playing with Lorca's forms, with his repetitions, his

arrangements of sequence and line. At times we found the need

to make the poems leaner than the original, with less of Lorca's

overwhelming language and cadences in Spanish. All this play,

this erasure, has seemed necessary to retain the feeling, the power,

the music of Lorca's work.

This was obviously one of the more creative and sensitive

parts of the collaboration. Here were two poets translating, writing, re-writing a poem, a book of poems, an activity that, to cite

Robert Lowell, in some way functions as an imitation of another

poet. Here were two poets translating, writing, rewriting a book of

poems that, to cite Gregory Rabassa, will become the version for

numerous (we hope) other readers. In giving ourselves leave to

be more than a combination dictionary/grammar/usage text, we

demanded of ourselves a great deal of humility and a bit of hubris, demanded the necessity of allowing the poetic ego to work

and the necessity to also say no to that very ego. Because, in thinking about how I as a poet or how we as poets would do this, we

were also responsible for remembering that often that very question, the one framed by the I or the we, while satisfying to think

about, may also be irrelevant to the poem we were translating. As

such, translating Lorca, arguably the greatest Spanish poet of the twentieth century, and Poet in New York, arguably his greatest book

of poems, has required reverence and irreverence, caution and

wildness, timidity and chutzpah.

To read Poet in New York in the version we offer here is to read

not prophecy but chronicle, not the future but the present. We

have lost the New York City of September 10, 2001. What we

gained is a New York in some ways wiser, sadder, and perhaps

better able to deal with both triumph and tragedy. We cannot

quantify grief, nor can we quantify hope. They are not found in

mourning prayers or in hate, not in the call to arms or in prejudice, not in money or fast cars or the most glittering jewels or the

tallest buildings or the smartest books. These are ancient lessons

Lorca learned well in New York, and we, lulled into complacency

by our collective wealth, forgot and relearned in a nightmare of

fire and ash. To read this book now is to see Lorca's eyes-eyes of

a child-staring from the anonymous grave into which he was

thrown after his murder and to hear the black sounds of duende

carried by the Spanish breeze above our buildings and streets to a

place where true grief and hope, twin sisters, reside.

Poeta en Nueva York / Poet in New York

A BEBE Y CARLOS MORLA

Los poemas de este libro estdn escritos en la ciudad de Nueva

York el ano 1929-1930, en que el poeta vivio como estudiante en

Columbia University.

F.G.L.

TO BEBE AND CARLOS MORLA

The poems of this book were written in the city of New York during

the year 1929-1930, in which the poet lived as a student at

Columbia University.

F.G.L.

I

Poemas de la soledad

en Columbia University

Furia color de amor,

amor color de olvido.

-Luis Cernuda

I

Poems of Solitude

at Columbia University

Fury, the color of love,

love, the color of forgetting.

-Luis Cernuda

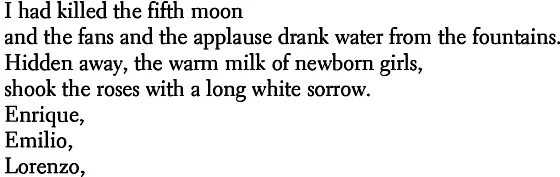

VUELTA DE PASEO

BACK FROM A WALK

1910

(Intermedio)

New York, agosto 1929

1910

(Interlude)

New York, August 1929

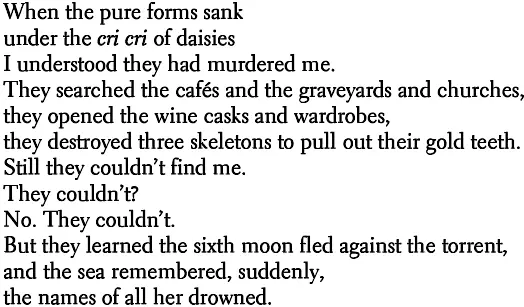

FABULA Y RUEDA DE LOS TRES AMIGOS

FABLE AND ROUND OF THE THREE FRIENDS

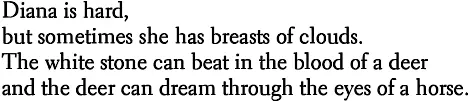

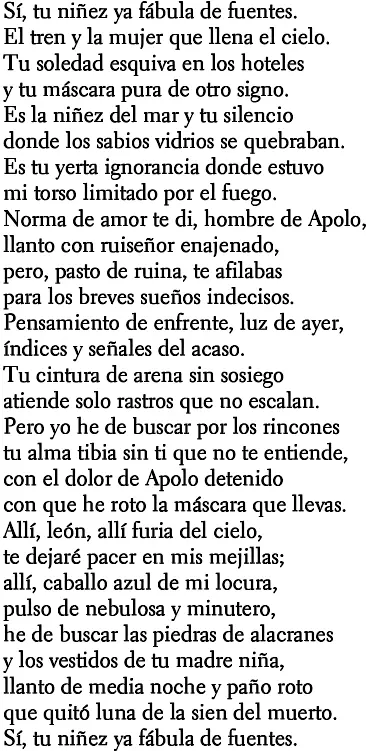

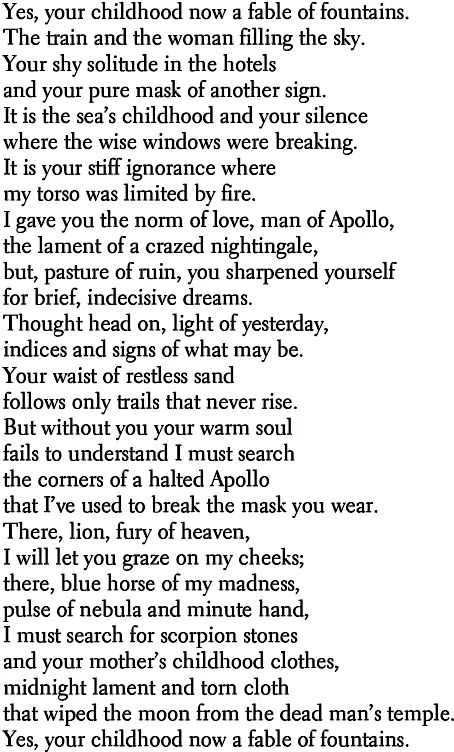

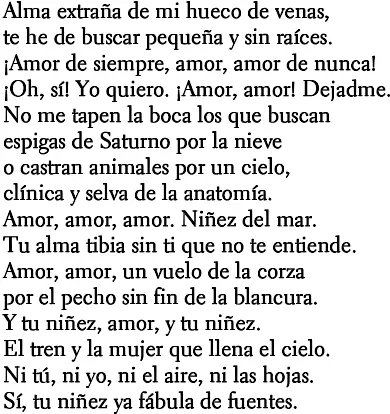

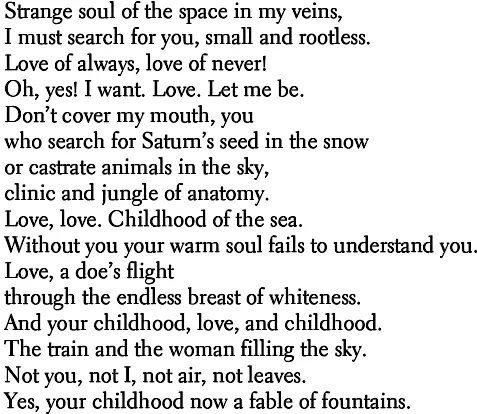

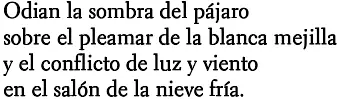

TU INFANCIA EN MENTON

Si, to ninez ya fabula de fuentes.

-Jorge Guillen

YOUR INFANCY IN MENTON

Yes, your childhood now a fable of fountains.

-Jorge Guillen

II

Los Negros

Para Angel del Rio

II

The Blacks

For Angel del Rio

NORMA Y PARAISO DE LOS NEGROS

NORM AND PARADISE OF THE BLACKS

EL REY DE HARLEM

THE KING OF HARLEM

IGLESIA ABANDONADA

(Balada de la Gran Guerra)

ABANDONED CHURCH

(Ballad of the Great War)

III

Calles y suenos

A Rafael R. Raptin

Un pdjaro de papel en el pecho

dice que el tiempo de los besos no ha llegado.

-Vicente Aleixandre

III

Streets and Dreams

To Rafael R. Radon

A paper bird in the breast

says the time of kisses has not arrived.

-Vicente Aleixandre

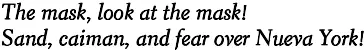

DANZA DE LA MUERTE

DANCE OF DEATH

Diciembre 1929

December 1929

PAISAJE DE LA MULTITUD QUE VOMITA

(Anochecer de Coney Island)

LANDSCAPE OF THE VOMITING CROWD

(Twilight at Coney Island)

New York, 29 de diciembre de 1929.

New York, December 29, 1929

PAISAJE DE LA MULTITUD QUE ORINA

(Nocturno de Battery Place)

LANDSCAPE OF THE URINATING CROWD

(Nocturne of Battery Place)

ASESINATO

(Dos voces de madrugada en Riverside Drive)

MURDER

(Two voices at dawn on Riverside Drive)

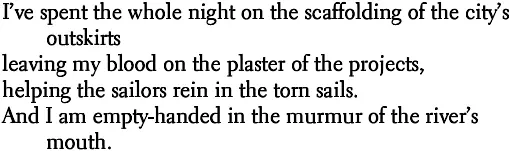

NAVIDAD EN EL HUDSON

CHRISTMAS ON THE HUDSON

New York, 27 de diciembre de 1929

New York, December 27, 1929

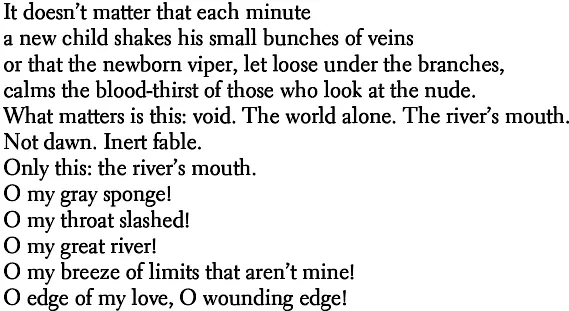

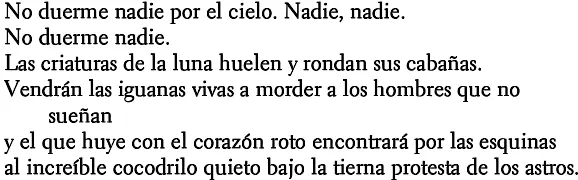

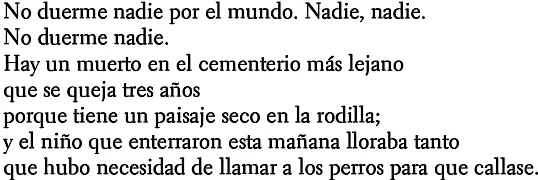

CIUDAD SIN SUENO

(Nocturno del Brooklyn Bridge)

CITY WITHOUT SLEEP

(Nocturne of the Brooklyn Bridge)

PANORAMA CIEGO DE NUEVA YORK

BLIND PANORAMA OF NEW YORK

NACIMIENTO DE CRISTO

BIRTH OF CHRIST

LA AURORA

DAWN

IV

Poemas del lago Eden Mills

A Eduardo Ugarte

IV

Poems of Lake Eden Mills

To Eduardo Ugarte

POEMA DOBLE DEL LAGO EDEN

Nuestro ganado pace, el viento espira.

-Garcilaso

DOUBLE POEM OF LAKE EDEN

Our cattle graze, the wind exhales.

-Garcilaso

CIELO VIVO

LIVING SKY

Eden Mills, Vermont, 24 agosto 1929

Eden Mills, Vermont

August 24, 1929

V

En la cabana del Farmer

(Campo de Newburg)

A Concha Mendez y Manuel Altolaguirre

V

In the Farmer's Cabin

(Newburgh Countryside)

To Concha Mendez and Manuel Altolaguirre

EL NINO STANTON

THE BOY STANTON

VACA

A Luis Lacasa

COW

To Luis Lacasa

NINA AHOGADA EN EL POZO

(Granada y Newburg)

GIRL DROWNED IN THE WELL

(Granada and Newburgh)

VI

Introduccion a la muerte

Poemas de la soledad en Vermont

Para Rafael Sanchez Ventura

VI

Introduction to Death

Poems of Solitude in Vermont

For Rafael Sanchez Ventura

MUERTE

A Luis de la Serna

DEATH

For Luis de la Serna

NOCTURNO DEL HUECO

1.

NOCTURNE OF THE HOLE

1.

II.

It

PAISAJE CON DOS TUMBAS Y UN PERRO ASIRIO

LANDSCAPE WITH TWO TOMBS AND AN ASSYRIAN DOG

RUINA

A Regino Sainz de la Maza

RUIN

To Regino Sainz de la Maza

LUNA Y PANORAMA DE LOS INSECTOS

(Poema de amor)

La luna en el rear riela,

en la Iona gime el viento

y alza en blando movimiento

olas de Plata y azul.

- Espronceda

MOON AND PANORAMA OF THE INSECTS

(Love Poem)

On the ocean the moon shimmers,

on the canvas the wind moans

and lifts in slow modulation

waves of silver and blue.

- Espronceda

New York, 4 de enero de 1930

New York, January 4, 1930

VII

Vuelta a la ciudad

Para Antonio Hernandez Soriano

VII

Return to the City

For Antonio Hernandez Soriano

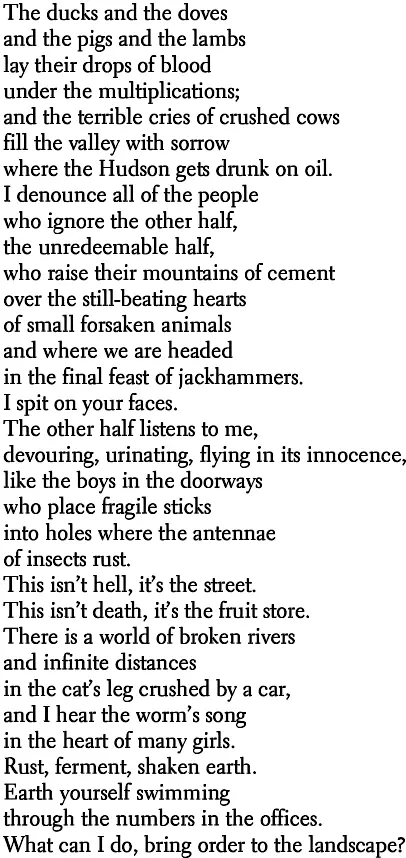

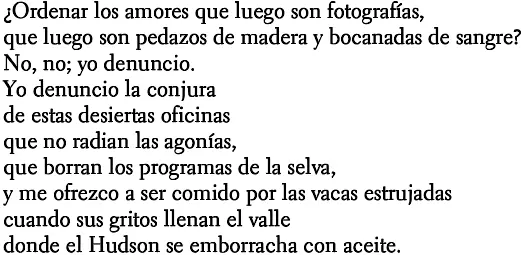

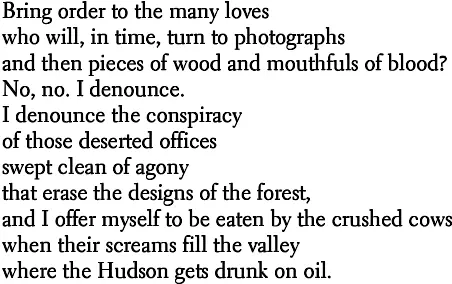

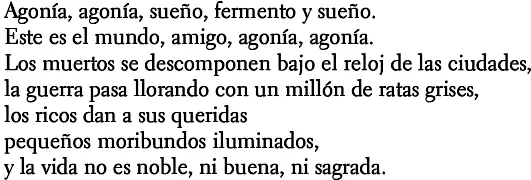

NEW YORK

Oficina y Denttncia

A Fernando Vela

NEW YORK

Office and Denunciation

To Fernando Vela

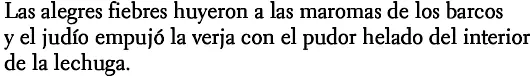

CEMENTERIO JUDIO

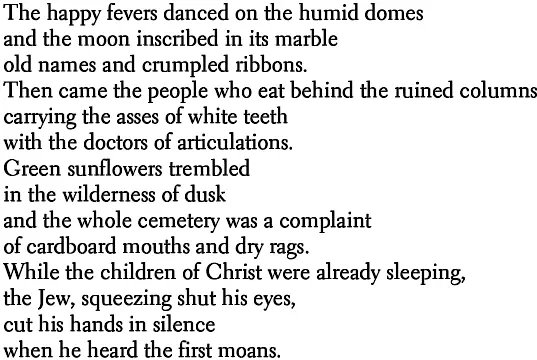

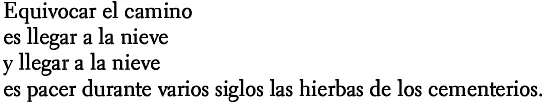

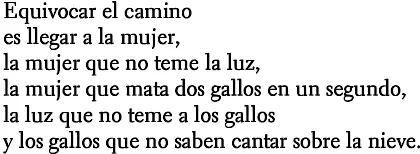

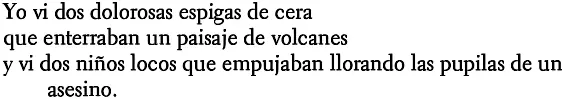

JEWISH CEMETERY

New York, 18 de enero de 1930

New York, January i8, 1930

PEQUENO POEMA INFINITO

Para Luis Cardoza y Aragon

SMALL INFINITE POEM

For Luis Cardoza y Aragon

New York, io de enero de 1930

New York, January io, 1930

CRUCIFIXION

CRUCIFIXION

New York, i8 de octubre de 1929

New York, October i8, 1929

VIII

Dos odas

A mi editor, Armando Guibert

VIII

Two Odes

To my editor, Armando Guibert

GRITO HACIA ROMA

(desde la torre del Chrysler Building)

CRY TOWARD ROME

(From the Tower of the Chrysler Building)

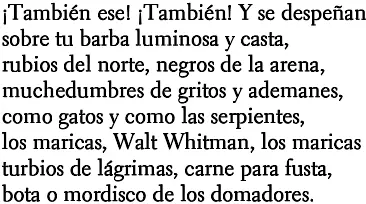

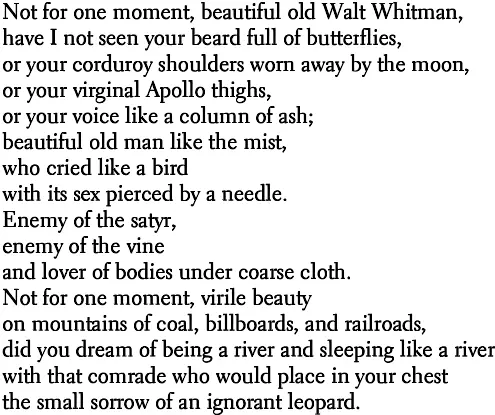

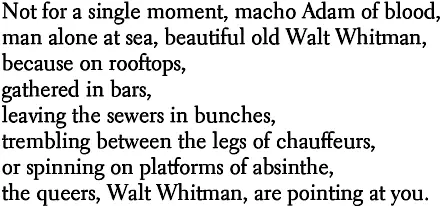

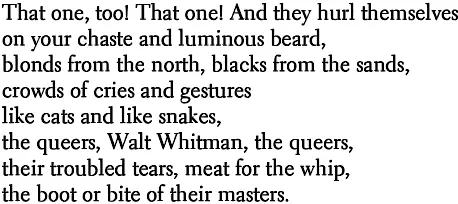

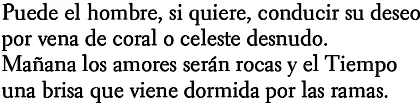

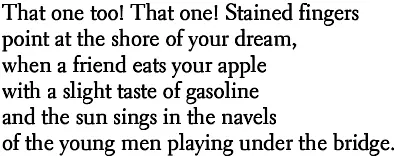

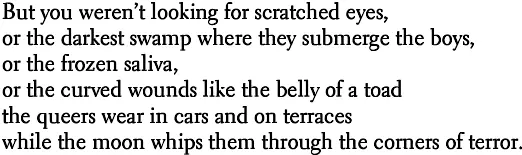

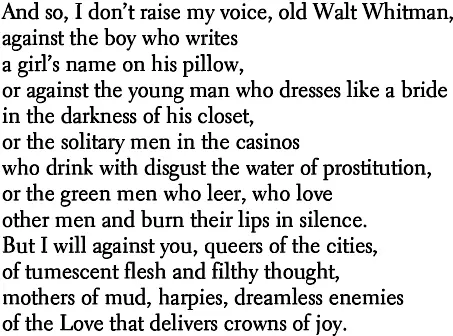

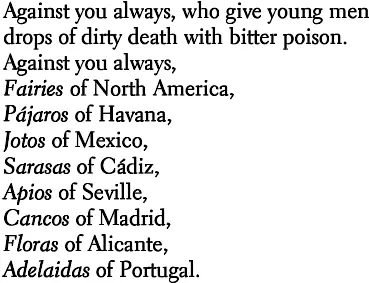

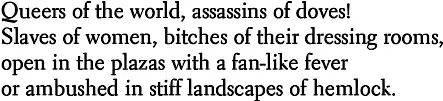

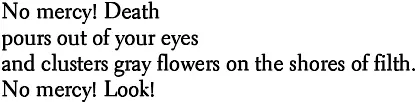

ODA A WALT WHITMAN

ODE TO WALT WHITMAN

ix

Huida de Nueva York

Dos valses hacia la civilizacion

IX

Flight from New York

Two Waltzes Toward Civilization

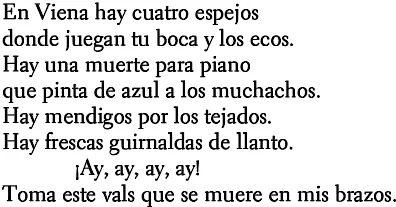

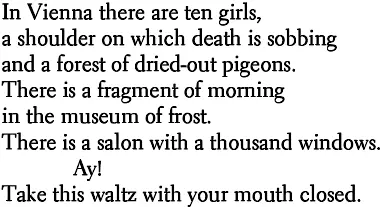

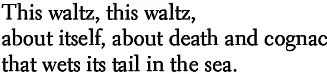

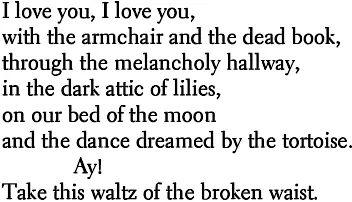

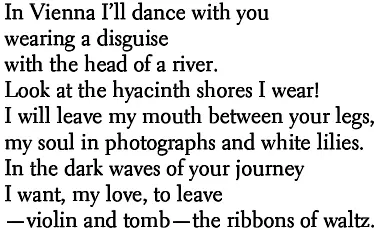

SMALL VIENNESE WALTZ

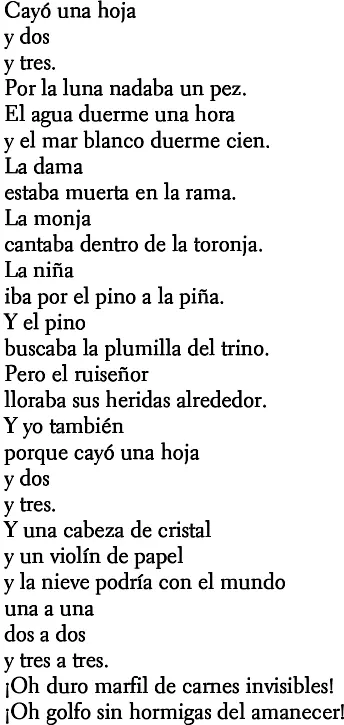

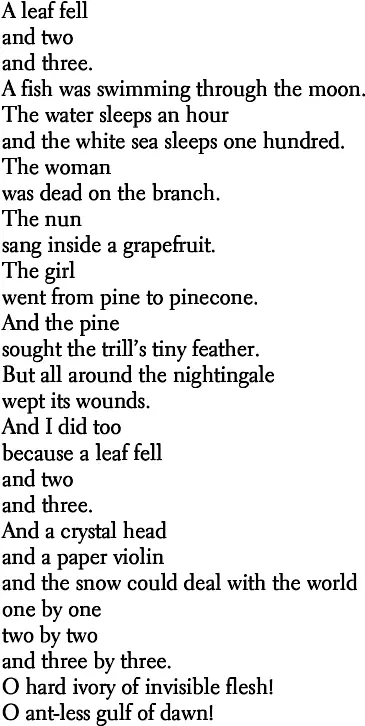

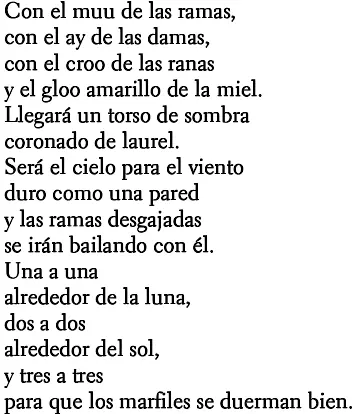

VALS EN LAS RAMAS

WALTZ IN THE BRANCHES

x

El Poeta llega a la Habana

A don Fernando Ortiz

X

The Poet Arrives in Havana

To Don Fernando Ortiz

SON DE NEGROS EN CUBA

SON OF BLACKS IN CUBA

Acknowledgments

As translators, we wish to thank los herederos of Federico Garcia

Lorca for their generosity. Elaine Markson, our agent, and Gary

Johnson, her assistant, provided invaluable encouragement and

expertise. Elisabeth Schmitz and Grove/Atlantic showed unwavering faith in the project from the very beginning. We are grateful for the support of of our colleagues at Eugene Lang College,

The New School for Liberal Arts, and the University of Nevada,

Las Vegas. Beth Vogel, Katherine Koch, Karen Koch, Pablo

Medina, Sr., and Ron Padgett read parts of the manuscript and

offered helpful and timely suggestions. Also helpful was Edward

Hirsch, who wrote the Foreword. The Black Mountain Institute

provided invaluable administrative support. The Virginia Center

for the Creative Arts provided a residency for Mark Statman. We

are also grateful to the members and staff of the Association of Writers and Writing Programs for their interest and their response to

this project.

1 comment