And Sordello

43

43 continued: “Let us now descend among

the great shades in the valley; we shall speak

with them; and seeing you, they will be pleased.”

46

46 I think that I had taken but three steps

to go below, when I saw one who watched →

attentively, trying to recognize me.

49

49 The hour had now arrived when air grows dark,

but not so dark that it deprived my eyes

and his of what—before—they were denied.

52

52 He moved toward me, and I advanced toward him.

Noble Judge Nino—what delight was mine →

when I saw you were not among the damned!

55

55 There was no gracious greeting we neglected

before he asked me: “When did you arrive,

across long seas, beneath this mountainside?”

58

58 I told him, “Oh, by way of the sad regions,

I came this morning; I am still within

the first life—although, by this journeying,

61

61 I earn the other.” When they heard my answer, →

Sordello and Judge Nino, just behind him,

drew back like people suddenly astonished.

64

64 One turned to Virgil, and the other turned →

and called to one who sat there: “Up, Currado! →

Come see what God, out of His grace, has willed!”

67

67 Then, when he turned to me: “By that especial

gratitude you owe to Him who hides

his primal aim so that no human mind

70

70 may find the ford to it, when you return

across the wide waves, ask my own Giovanna— →

there where the pleas of innocents are answered—

73

73 to pray for me. I do not think her mother

still loves me: she gave up her white veils—surely,

poor woman, she will wish them back again.

76

76 Through her, one understands so easily

how brief, in woman, is love’s fire—when not

rekindled frequently by eye or touch.

79

79 The serpent that assigns the Milanese →

their camping place will not provide for her

a tomb as fair as would Gallura’s rooster.”

82

82 So Nino spoke; his bearing bore the seal

of that unswerving zeal which, though it flames

within the heart, maintains a sense of measure.

85

85 My avid eyes were steadfast, staring at

that portion of the sky where stars are slower, →

even as spokes when they approach the axle.

88

88 And my guide: “Son, what are you staring at?”

And I replied: “I’m watching those three torches →

with which this southern pole is all aflame.”

91

91 Then he to me: “The four bright stars you saw

this morning now are low, beyond the pole,

and where those four stars were, these three now are.”

94

94 Even as Virgil spoke, Sordello drew

him to himself: “See there—our adversary!” →

he said; and then he pointed with his finger.

97

97 At the unguarded edge of that small valley,

there was a serpent—similar, perhaps,

to that which offered Eve the bitter food.

100

100 Through grass and flowers the evil streak advanced;

from time to time it turned its head and licked

its back, like any beast that preens and sleeks.

103

103 I did not see—and therefore cannot say—just

how the hawks of heaven made their move, →

but I indeed saw both of them in motion.

106

106 Hearing the green wings cleave the air, the serpent

fled, and the angels wheeled around as each

of them flew upward, back to his high station.

109

109 The shade who, when the judge had called, had drawn →

closer to him, through all of that attack,

had not removed his eyes from me one moment.

112

112 “So may the lantern that leads you on high

discover in your will the wax one needs—

enough for reaching the enameled peak,”

115

115 that shade began, “if you have heard true tidings

of Val di Magra or the lands nearby,

tell them to me—for there I once was mighty.

118

118 Currado Malaspina was my name;

I’m not the old Currado, but I am

descended from him: to my own I bore

121

121 the love that here is purified.” I answered:

“never visited your lands; but can

there be a place in all of Europe where

124

124 they are not celebrated? Such renown

honors your house, acclaims your lords and lands—

even if one has yet to journey there.

127

127 And so may I complete my climb, I swear

to you: your honored house still claims the prize—

the glory of the purse and of the sword.

130

130 Custom and nature privilege it so

that, though the evil head contorts the world, →

your kin alone walk straight and shun the path

133

133 of wickedness.” And he: “Be sure of that.

The sun will not have rested seven times →

within the bed that’s covered and held fast

136

136 by all the Ram’s four feet before this gracious

opinion’s squarely nailed into your mind

with stouter nails than others’ talk provides—

139

139 if the divine decree has not been stayed.”

Ante-Purgatory. The Valley of the Rulers. Aurora in the northern hemisphere and night in Purgatory. The sleep of Dante. His dream of the Eagle. His waking at morning. The guardian angel. The gate of Purgatory. The seven P’s. Entry.

Now she who shares the bed of old Tithonus, →

abandoning the arms of her sweet lover,

grew white along the eastern balcony;

4

4 the heavens facing her were glittering

with gems set in the semblance of the chill

animal that assails men with its tail;

7

7 while night within the valley where we were

had moved across two of the steps it climbs,

and now the third step made night’s wings incline;

10

10 when I, who bore something of Adam with me, →

feeling the need for sleep, lay down upon

the grass where now all five of us were seated. →

13

13 At that hour close to morning when the swallow →

begins her melancholy songs, perhaps

in memory of her ancient sufferings,

16

16 when, free to wander farther from the flesh →

and less held fast by cares, our intellect’s

envisionings become almost divine—

19

19 in dream I seemed to see an eagle poised, →

with golden pinions, in the sky: its wings

were open; it was ready to swoop down.

22

22 And I seemed to be there where Ganymede →

deserted his own family when he

was snatched up for the high consistory.

25

25 Within myself I thought: “This eagle may

be used to hunting only here; its claws

refuse to carry upward any prey

28

28 found elsewhere.” Then it seemed to me that, wheeling

slightly and terrible as lightning, it

swooped, snatching me up to the fire’s orbit. →

31

31 And there it seemed that he and I were burning;

and this imagined conflagration scorched

me so—I was compelled to break my sleep.

34

34 Just like the waking of Achilles when →

he started up, casting his eyes about him,

not knowing where he was (after his mother

37

37 had stolen him, asleep, away from Chiron

and in her arms had carried him to Skyros,

the isle the Greeks would—later—make him leave);

40

40 such was my starting up, as soon as sleep

had left my eyes, and I went pale, as will

a man who, terrified, turns cold as ice. →

43

43 The only one beside me was my comfort;

by now the sun was more than two hours high; →

it was the sea to which I turned my eyes.

46

46 My lord said: “Have no fear; be confident,

for we are well along our way; do not

restrain, but give free rein to, all your strength.

49

49 You have already come to Purgatory: →

see there the rampart wall enclosing it;

see, where that wall is breached, the point of entry.

52

52 Before, at dawn that ushers in the day,

when soul was sleeping in your body, on

the flowers that adorn the ground below,

55

55 a lady came; she said: ‘I am Lucia; →

let me take hold of him who is asleep,

that I may help to speed him on his way.’

58

58 Sordello and the other noble spirits

stayed there; and she took you, and once the day

was bright, she climbed—I following behind.

61

61 And here she set you down, but first her lovely

eyes showed that open entryway to me;

then she and sleep together took their leave.”

64

64 Just like a man in doubt who then grows sure,

exchanging fear for confidence, once truth

has been revealed to him, so was I changed;

67

67 and when my guide had seen that I was free

from hesitation, then he moved, with me

behind him, up the rocks and toward the heights.

70

70 Reader, you can see clearly how I lift

my matter; do not wonder, therefore, if

I have to call on more art to sustain it.

73

73 Now we were drawing closer; we had reached

the part from which—where first I’d seen a breach,

precisely like a gap that cleaves a wall—

76

76 I now made out a gate and, there below it,

three steps—their colors different—leading to it,

and a custodian who had not yet spoken. →

79

79 As I looked more and more directly at him,

I saw him seated on the upper step—

his face so radiant, I could not bear it;

82

82 and in his hand he held a naked sword, →

which so reflected rays toward us that I,

time and again, tried to sustain that sight

85

85 in vain. “Speak out from there; what are you seeking?”

so he began to speak. “Where is your escort? →

Take care lest you be harmed by climbing here.”

88

88 My master answered him: “But just before,

a lady came from Heaven and, familiar

with these things, told us: ‘That’s the gate; go there.’ ”

91

91 “And may she speed you on your path of goodness!”

the gracious guardian of the gate began

again. “Come forward, therefore, to our stairs.”

94

94 There we approached, and the first step was white →

marble, so polished and so clear that I

was mirrored there as I appear in life.

97

97 The second step, made out of crumbling rock,

rough-textured, scorched, with cracks that ran across

its length and width, was darker than deep purple.

100

100 The third, resting above more massively,

appeared to me to be of porphyry,

as flaming red as blood that spurts from veins.

103

103 And on this upper step, God’s angel—seated →

upon the threshold, which appeared to me

to be of adamant—kept his feet planted.

106

106 My guide, with much good will, had me ascend

by way of these three steps, enjoining me:

“Do ask him humbly to unbolt the gate.”

109

109 I threw myself devoutly at his holy

feet, asking him to open out of mercy;

but first I beat three times upon my breast.

112

112 Upon my forehead, he traced seven P’s →

with his sword’s point and said: “When you have entered

within, take care to wash away these wounds.”

115

115 Ashes, or dry earth that has just been quarried, →

would share one color with his robe, and from →

beneath that robe he drew two keys; the one

118

118 was made of gold, the other was of silver; →

first with the white, then with the yellow key,

he plied the gate so as to satisfy me.

121

121 “Whenever one of these keys fails, not turning

appropriately in the lock,” he said

to us, “this gate of entry does not open.

124

124 One is more precious, but the other needs

much art and skill before it will unlock—

that is the key that must undo the knot.

127

127 These I received from Peter; and he taught me →

rather to err in opening than in keeping

this portal shut—whenever souls pray humbly.”

130

130 Then he pushed back the panels of the holy

gate, saying: “Enter; but I warn you—he →

who would look back, returns—again—outside.”

133

133 And when the panels of that sacred portal, →

which are of massive and resounding metal,

turned in their hinges, then even Tarpeia

136

136 (when good Metellus was removed from it,

for which that rock was left impoverished)

did not roar so nor show itself so stubborn.

139

139 Hearing that gate resound, I turned, attentive;

I seemed to hear, inside, in words that mingled

with gentle music, “Te Deum laudamus.” →

142

142 And what I heard gave me the very same

impression one is used to getting when

one hears a song accompanied by organ, →

145

145 and now the words are clear and now are lost.

Click here to go to the line

Click here to go to the line

The First Terrace: the Prideful. The hard ascent. The sculptured wall with three examples of humility: the Virgin Mary, David, and Trajan. The Prideful punished by bearing the weight of heavy stones.

When I had crossed the threshold of the gate

that—since the soul’s aberrant love would make

the crooked way seem straight—is seldom used,

4

4 I heard the gate resound and, hearing, knew →

that it had shut; and if I’d turned toward it, →

how could my fault have found a fit excuse?

7

7 Our upward pathway ran between cracked rocks; →

they seemed to sway in one, then the other part,

just like a wave that flees, then doubles back.

10

10 “Here we shall need some ingenuity,”

my guide warned me, “as both of us draw near

this side or that side where the rock wall veers.”

13

13 This made our steps so slow and hesitant →

that the declining moon had reached its bed

to sink back into rest, before we had

16

16 made our way through that needle’s eye; but when

we were released from it, in open space

above, a place at which the slope retreats, →

19

19 I was exhausted; with the two of us

uncertain of our way, we halted on

a plateau lonelier than desert paths.

22

22 The distance from its edge, which rims the void,

in to the base of the steep slope, which climbs

and climbs, would measure three times one man’s body;

25

25 and for as far as my sight took its flight,

now to the left, now to the right-hand side,

that terrace seemed to me equally wide.

28

28 There we had yet to let our feet advance

when I discovered that the bordering bank— →

less sheer than banks of other terraces—

31

31 was of white marble and adorned with carvings

so accurate—not only Polycletus →

but even Nature, there, would feel defeated.

34

34 The angel who reached earth with the decree →

of that peace which, for many years, had been

invoked with tears, the peace that opened Heaven

37

37 after long interdict, appeared before us,

his gracious action carved with such precision—

he did not seem to be a silent image.

40

40 One would have sworn that he was saying, “Ave”; →

for in that scene there was the effigy

of one who turned the key that had unlocked

43

43 the highest love; and in her stance there were

impressed these words, “Ecce ancilla Dei,” →

precisely like a figure stamped in wax.

46

46 “Your mind must not attend to just one part,”

the gentle master said—he had me on

the side of him where people have their heart.

49

49 At this, I turned my face and saw beyond

the form of Mary—on the side where stood

the one who guided me—another story

52

52 engraved upon the rock; therefore I moved

past Virgil and drew close to it, so that

the scene before my eyes was more distinct.

55

55 There, carved in that same marble, were the cart

and oxen as they drew the sacred ark, →

which makes men now fear tasks not in their charge.

58

58 People were shown in front; and all that group,

divided into seven choirs, made

two of my senses speak—one sense said, “No,”

61

61 the other said, “Yes, they do sing”; just so,

about the incense smoke shown there, my nose

and eyes contended, too, with yes and no.

64

64 And there the humble psalmist went before

the sacred vessel, dancing, lifting up

his robe—he was both less and more than king.

67

67 Facing that scene, and shown as at the window

of a great palace, Michal watched as would

a woman full of scorn and suffering.

70

70 To look more closely at another carving,

which I saw gleaming white beyond Michal,

my feet moved past the point where I had stood.

73

73 And there the noble action of a Roman →

prince was presented—he whose worth had urged

on Gregory to his great victory—

76

76 I mean the Emperor Trajan; and a poor

widow was near his bridle, and she stood

even as one in tears and sadness would.

79

79 Around him, horsemen seemed to press and crowd;

above their heads, on golden banners, eagles

were represented, moving in the wind.

82

82 Among that crowd, the miserable woman

seemed to be saying: “Lord, avenge me for

the slaying of my son—my heart is broken.”

85

85 And he was answering: “Wait now until

I have returned.” And she, as one in whom

grief presses urgently: “And, lord, if you

88

88 do not return?” And he: “The one who’ll be

in my place will perform it for you.” She:

“What good can others’ goodness do for you

91

91 if you neglect your own?” He: “Be consoled;

my duty shall be done before I go:

so justice asks, so mercy makes me stay.”

94

94 This was the speech made visible by One →

within whose sight no thing is new—but we,

who lack its likeness here, find novelty.

97

97 While I took much delight in witnessing

these effigies of true humility—

dear, too, to see because He was their Maker—

100

100 the poet murmured: “See the multitude

advancing, though with slow steps, on this side:

they will direct us to the higher stairs.”

103

103 My eyes, which had been satisfied in seeking

new sights—a thing for which they long—did not

delay in turning toward him. But I would

106

106 not have you, reader, be deflected from

your good resolve by hearing from me now

how God would have us pay the debt we owe. →

109

109 Don’t dwell upon the form of punishment: →

consider what comes after that; at worst

it cannot last beyond the final Judgment.

112

112 “Master,” I said, “what I see moving toward us →

does not appear to me like people, but

I can’t tell what is there—my sight’s bewildered.”

115

115 And he to me: “Whatever makes them suffer

their heavy torment bends them to the ground;

at first I was unsure of what they were.

118

118 But look intently there, and let your eyes

unravel what’s beneath those stones: you can

already see what penalty strikes each.”

121

121 O Christians, arrogant, exhausted, wretched,

whose intellects are sick and cannot see,

who place your confidence in backward steps, →

124

124 do you not know that we are worms and born

to form the angelic butterfly that soars, →

without defenses, to confront His judgment?

127

127 Why does your mind presume to flight when you

are still like the imperfect grub, the worm

before it has attained its final form?

130

130 Just as one sees at times—as corbel for →

support of ceiling or of roof—a figure

with knees drawn up into its chest (and this

133

133 oppressiveness, unreal, gives rise to real

distress in him who watches it): such was

the state of those I saw when I looked hard.

136

136 They were indeed bent down—some less, some more—according

to the weights their backs now bore;

and even he whose aspect showed most patience,

139

139 in tears, appeared to say: “I can no more.”

Still on the First Terrace: the Prideful, who now pray a paraphrase of the Lord’s Prayer. Omberto Aldobrandeschi. Oderisi of Gubbio: his discourse on earthly fame; his presentation of Provenzan Salvani.

Our Father, You who dwell within the heavens— →

but are not circumscribed by them—out of →

Your greater love for Your first works above,

4

4 praised be Your name and Your omnipotence, →

by every creature, just as it is seemly

to offer thanks to Your sweet effluence.

7

7 Your kingdom’s peace come unto us, for if →

it does not come, then though we summon all

our force, we cannot reach it of our selves.

10

10 Just as Your angels, as they sing Hosanna,

offer their wills to You as sacrifice,

so may men offer up their wills to You.

13

13 Give unto us this day the daily manna →

without which he who labors most to move

ahead through this harsh wilderness falls back.

16

16 Even as we forgive all who have done

us injury, may You, benevolent,

forgive, and do not judge us by our worth.

19

19 Try not our strength, so easily subdued,

against the ancient foe, but set it free →

from him who goads it to perversity.

22

22 This last request we now address to You, →

dear Lord, not for ourselves—who have no need—

but for the ones whom we have left behind.”

25

25 Beseeching, thus, good penitence for us

and for themselves, those shades moved on beneath

their weights, like those we sometimes bear in dreams—

28

28 each in his own degree of suffering

but all, exhausted, circling the first terrace,

purging themselves of this world’s scoriae.

31

31 If there they pray on our behalf, what can →

be said and done here on this earth for them

by those whose wills are rooted in true worth?

34

34 Indeed we should help them to wash away

the stains they carried from this world, so that,

made pure and light, they reach the starry wheels. →

37

37 “Ah, so may justice and compassion soon

unburden you, so that your wings may move

as you desire them to, and uplift you,

40

40 show us on which hand lies the shortest path

to reach the stairs; if there is more than one

passage, then show us that which is less steep;

43

43 for he who comes with me, because he wears

the weight of Adam’s flesh as dress, despite

his ready will, is slow in his ascent.”

46

46 These words, which had been spoken by my guide,

were answered by still other words we heard;

for though it was not clear who had replied,

49

49 an answer came: “Come with us to the right

along the wall of rock, and you will find

a pass where even one alive can climb.

52

52 And were I not impeded by the stone →

that, since it has subdued my haughty neck,

compels my eyes to look below, then I

55

55 should look at this man who is still alive

and nameless, to see if I recognize

him—and to move his pity for my burden.

58

58 I was Italian, son of a great Tuscan: →

my father was Guiglielmo Aldobrandesco;

I do not know if you have heard his name.

61

61 The ancient blood and splendid deeds of my →

forefathers made me so presumptuous

that, without thinking on our common mother,

64

64 I scorned all men past measure, and that scorn

brought me my death—the Sienese know how,

as does each child in Campagnatico.

67

67 I am Omberto; and my arrogance

has not harmed me alone, for it has drawn

all of my kin into calamity.

70

70 Until God has been satisfied, I bear

this burden here among the dead because

I did not bear this load among the living.”

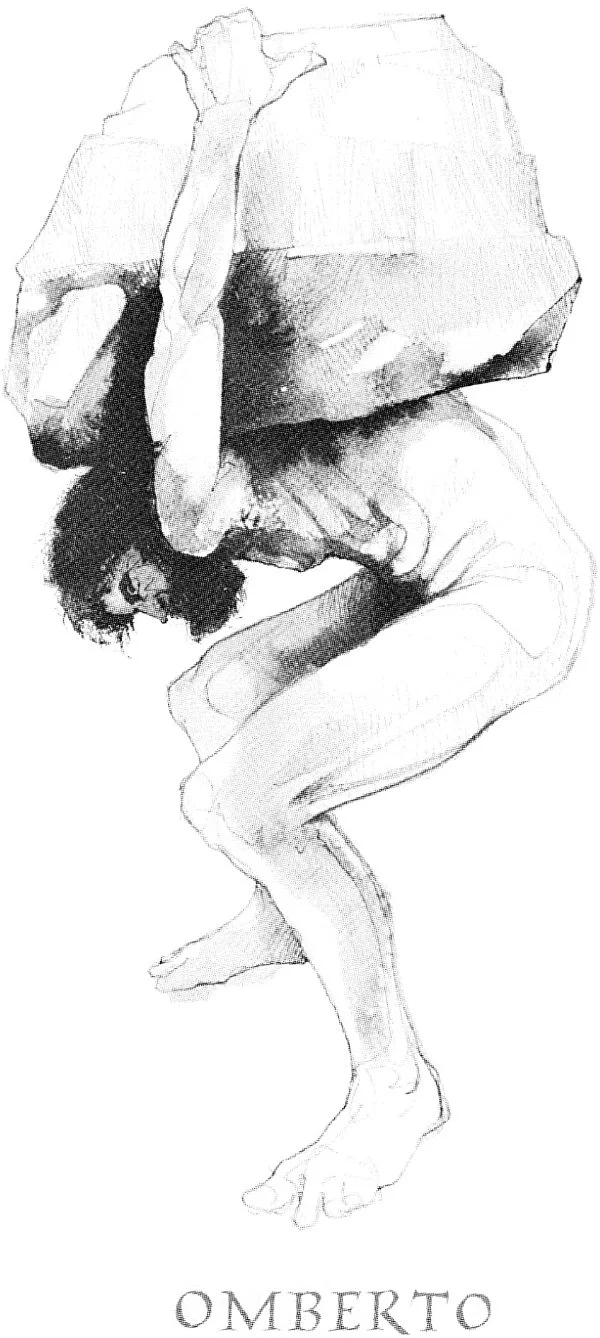

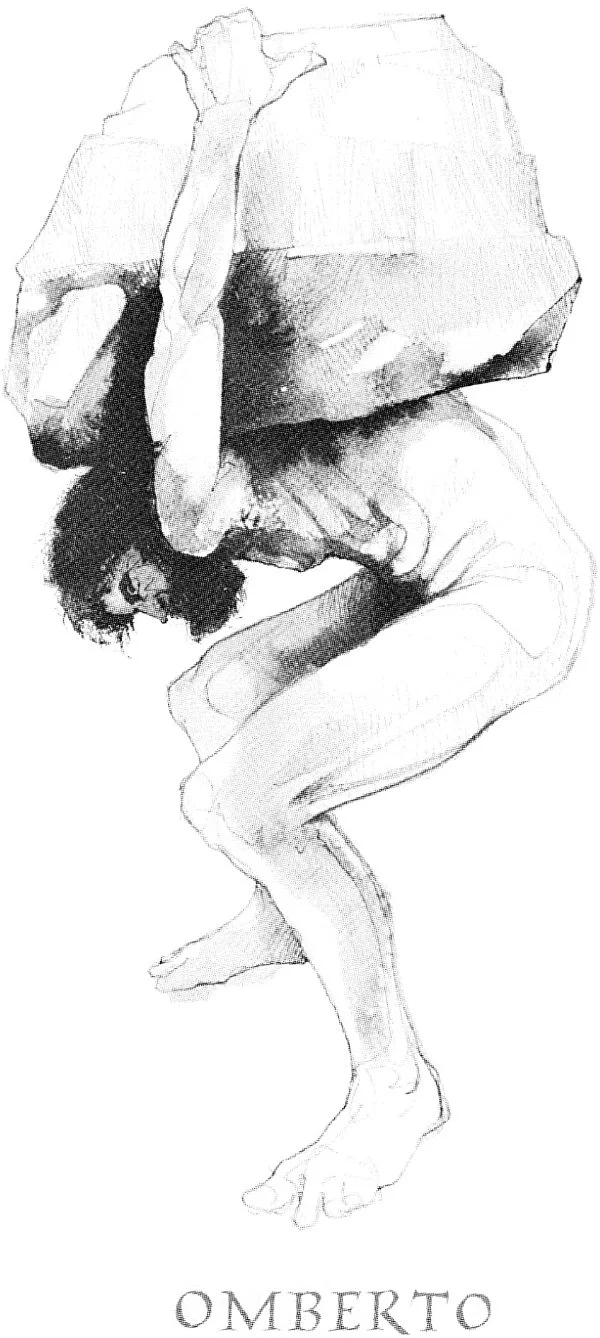

73

73 My face was lowered as I listened; and

one of those souls—not he who’d spoken—twisted →

himself beneath the weight that burdened them;

76

76 he saw and knew me and called out to me,

fixing his eyes on me laboriously

as I, completely hunched, walked on with them. →

79

79 “Oh,” I cried out, “are you not Oderisi, →

glory of Gubbio, glory of that art

they call illumination now in Paris?”

82

82 “Brother,” he said, “the pages painted by

the brush of Franco Bolognese smile →

more brightly: all the glory now is his;

85

85 mine, but a part. In truth I would have been

less gracious when I lived—so great was that

desire for eminence which drove my heart.

88

88 For such pride, here one pays the penalty;

and I’d not be here yet, had it not been

that, while I still could sin, I turned to Him.

91

91 O empty glory of the powers of humans!

How briefly green endures upon the peak— →

unless an age of dullness follows it.

94

94 In painting Cimabue thought he held →

the field, and now it’s Giotto they acclaim—

the former only keeps a shadowed fame.

97

97 So did one Guido, from the other, wrest →

the glory of our tongue—and he perhaps

is born who will chase both out of the nest.

100

100 Worldly renown is nothing other than

a breath of wind that blows now here, now there,

and changes name when it has changed its course.

103

103 Before a thousand years have passed—a span →

that, for eternity, is less space than

an eyeblink for the slowest sphere in heaven—

106

106 would you find greater glory if you left

your flesh when it was old than if your death

had come before your infant words were spent?

109

109 All Tuscany acclaimed his name—the man →

who moves so slowly on the path before me,

and now they scarcely whisper of him even

112

112 in Siena, where he lorded it when they

destroyed the raging mob of Florence—then

as arrogant as now it’s prostitute.

115

115 Your glory wears the color of the grass →

that comes and goes; the sun that makes it wither

first drew it from the ground, still green and tender.”

118

118 And I to him: “Your truthful speech has filled

my soul with sound humility, abating

my overswollen pride; but who is he

121

121 of whom you spoke now?” “Provenzan Salvani,

he answered, “here because—presumptuously—” →

he thought his grip could master all Siena.

124

124 So he has gone, and so he goes, with no

rest since his death; this is the penalty

exacted from those who—there—overreached.”

127

127 And I: “But if a spirit who awaits

the edge of life before repenting must—

unless good prayers help him—stay below

130

130 and not ascend here for as long a time

as he had spent alive, do tell me how

Salvani’s entry here has been allowed.”

133

133 “When he was living in his greatest glory,”

said he, “then of his own free will he set

aside all shame and took his place upon

136

136 the Campo of Siena; there, to free →

his friend from suffering in Charles’s prison,

humbling himself, he trembled in each vein.

139

139 I say no more; I know I speak obscurely; →

but soon enough you’ll find your neighbor’s acts

are such that what I say can be explained.

142

142 This deed delivered him from those confines.” →

Click here to go to the line

Click here to go to the line

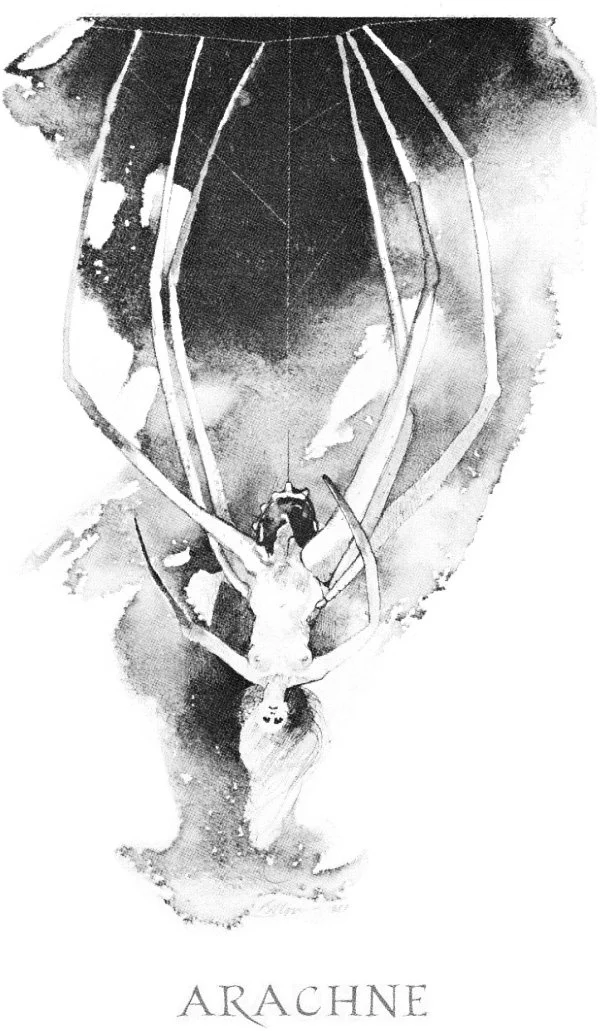

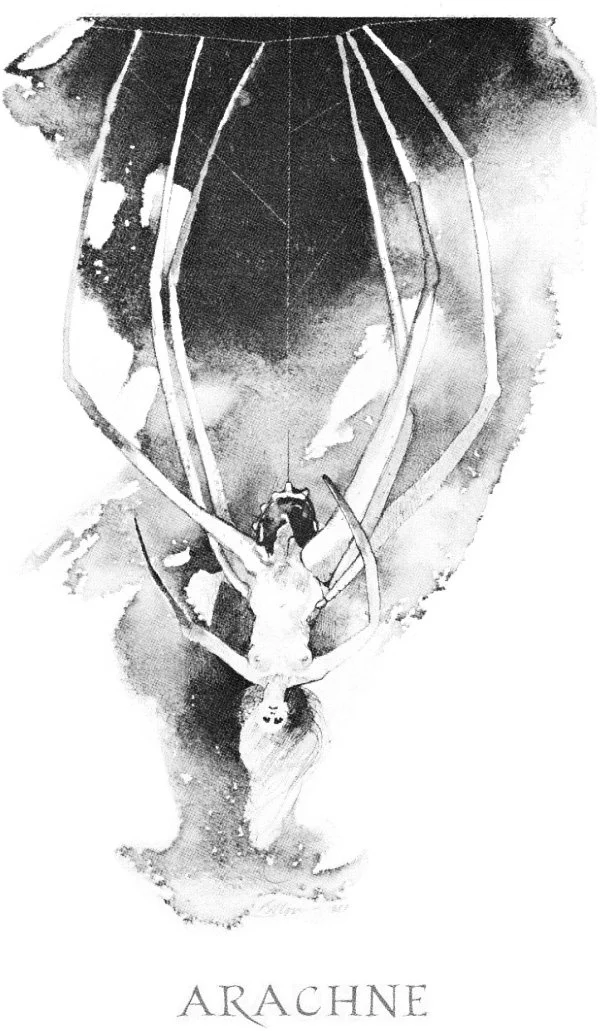

Still on the First Terrace: the Prideful. The sculptured pavement with thirteen examples of punished pride: Satan, Briareus, the Giants, Nimrod, Niobe, Saul, Arachne, Rehoboam, Eriphyle, Sennacherib, Cyrus, Holofernes, Troy. The angel of humility. Ascent to the Second Terrace. The First Beatitude. One P erased.

As oxen, yoked, proceed abreast, so I

moved with that burdened soul as long as my

kind pedagogue allowed me to; but when

4

4 he said: “Leave him behind, and go ahead;

for here it’s fitting that with wings and oars

each urge his boat along with all his force,”

7

7 I drew my body up again, erect—the

stance most suitable to man—and yet

the thoughts I thought were still submissive, bent.

10

10 Now I was on my way, and willingly

I followed in my teacher’s steps, and we

together showed what speed we could command.

13

13 He said to me: “Look downward, for the way

will offer you some solace if you pay

attention to the pavement at your feet.”

16

16 As, on the lids of pavement tombs, there are

stone effigies of what the buried were

before, so that the dead may be remembered;

19

19 and there, when memory—inciting only

the pious—has renewed their mourning, men

are often led to shed their tears again;

22

22 so did I see, but carved more skillfully,

with greater sense of likeness, effigies

on all the path protruding from the mountain.

25

25 I saw, to one side of the path, one who →

had been created nobler than all other →

beings, falling lightning-like from Heaven.

28

28 I saw, upon the other side, Briareus →

transfixed by the celestial shaft: he lay,

ponderous, on the ground, in fatal cold.

31

31 I saw Thymbraeus, I saw Mars and Pallas, →

still armed, as they surrounded Jove, their father,

gazing upon the Giants’ scattered limbs.

34

34 I saw bewildered Nimrod at the foot →

of his great labor; watching him were those

of Shinar who had shared his arrogance.

37

37 O Niobe, what tears afflicted me →

when, on that path, I saw your effigy

among your slaughtered children, seven and seven!

40

40 O Saul, you were portrayed there as one who →

had died on his own sword, upon Gilboa,

which never after knew the rain, the dew!

43

43 O mad Arachne, I saw you already →

half spider, wretched on the ragged remnants

of work that you had wrought to your own hurt!

46

46 O Rehoboam, you whose effigy →

seems not to menace there, and yet you flee

by chariot, terrified, though none pursues!

49

49 It also showed—that pavement of hard stone—how

much Alcmaeon made his mother pay: →

the cost of the ill-omened ornament.

52

52 It showed the children of Sennacherib →

as they assailed their father in the temple,

then left him, dead, behind them as they fled.

55

55 It showed the slaughter and the devastation →

wrought by Tomyris when she taunted Cyrus:

“You thirsted after blood; with blood I fill you.”

58

58 It showed the rout of the Assyrians, →

sent reeling after Holofernes’ death,

and also showed his body—what was left.

61

61 I saw Troy turned to caverns and to ashes; →

o Ilium, your effigy in stone—

it showed you there so squalid, so cast down!

64

64 What master of the brush or of the stylus

had there portrayed such masses, such outlines

as would astonish all discerning minds?

67

67 The dead seemed dead and the alive, alive:

I saw, head bent, treading those effigies,

as well as those who’d seen those scenes directly.

70

70 Now, sons of Eve, persist in arrogance,

in haughty stance, do not let your eyes bend,

lest you be forced to see your evil path!

73

73 We now had circled round more of the mountain

and much more of the sun’s course had been crossed

than I, my mind absorbed, had gauged, when he

76

76 who always looked ahead insistently,

as he advanced, began: “Lift up your eyes;

it’s time to set these images aside.

79

79 See there an angel hurrying to meet us, →

and also see the sixth of the handmaidens →

returning from her service to the day.

82

82 Adorn your face and acts with reverence,

that he be pleased to send us higher. Remember—

today will never know another dawn.”

85

85 I was so used to his insistent warnings

against the loss of time; concerning that,

his words to me could hardly be obscure.

88

88 That handsome creature came toward us; his clothes

were white, and in his aspect he seemed like

the trembling star that rises in the morning.

91

91 He opened wide his arms, then spread his wings;

he said: “Approach: the steps are close at hand;

from this point on one can climb easily.

94

94 This invitation’s answered by so few:

o humankind, born for the upward flight,

why are you driven back by wind so slight?”

97

97 He led us to a cleft within the rock,

and then he struck my forehead with his wing; →

that done, he promised me safe journeying.

100

100 As on the right, when one ascends the hill

where—over Rubaconte’s bridge—there stands →

the church that dominates the well-ruled city, →

103

103 the daring slope of the ascent is broken

by steps that were constructed in an age

when record books and measures could be trusted, →

106

106 so was the slope that plummets there so steeply

down from the other ring made easier;

but on this side and that, high rock encroaches.

109

109 While we began to move in that direction,

“Beati pauperes spiritu” was sung →

so sweetly—it can not be told in words.

112

112 How different were these entryways from those →

of Hell! For here it is with song one enters;

down there, it is with savage lamentations.

115

115 Now we ascended by the sacred stairs,

but I seemed to be much more light than I

had been, before, along the level terrace.

118

118 At this I asked: “Master, tell me, what heavy

weight has been lifted from me, so that I,

in going, notice almost no fatigue?”

121

121 He answered: “When the P’s that still remain

upon your brow—now almost all are faint—

have been completely, like this P, erased,

124

124 your feet will be so mastered by good will

that they not only will not feel travail

but will delight when they are urged uphill.”

127

127 Then I behaved like those who make their way

with something on their head of which they’re not

aware, till others’ signs make them suspicious,

130

130 at which, the hand helps them to ascertain;

it seeks and finds and touches and provides

the services that sight cannot supply;

133

133 so, with my right hand’s outspread fingers, I →

found just six of the letters once inscribed

by him who holds the keys, upon my forehead;

136

136 and as he watched me do this, my guide smiled.

The Second Terrace: the Envious. Virgil’s apostrophe to the sun. Voices calling out three incitements to fraternal love: the examples of the Virgin Mary and Orestes, and a dictum of Jesus. The Litany of the Saints.

1 comment