The Envious punished by having their eyelids sewn up with iron wires. Sapia of Siena.

We now had reached the summit of the stairs

where once again the mountain whose ascent

delivers man from sin has been indented.

4

4 There, just as in the case of the first terrace,

a second terrace runs around the slope,

except that it describes a sharper arc. →

7

7 No effigy is there and no outline: →

the bank is visible, the naked path—

only the livid color of raw rock.

10

10 “If we wait here in order to inquire

of those who pass,” the poet said, “I fear

our choice of path may be delayed too long.”

13

13 And then he fixed his eyes upon the sun;

letting his right side serve to guide his movement, →

he wheeled his left around and changed direction.

16

16 “O gentle light, through trust in which I enter

on this new path, may you conduct us here,”

he said, “for men need guidance in this place.

19

19 You warm the world and you illumine it;

unless a higher Power urge us elsewhere,

your rays must always be the guides that lead.”

22

22 We had already journeyed there as far

as we should reckon here to be a mile,

and done it in brief time—our will was eager—

25

25 when we heard spirits as they flew toward us, →

though they could not be seen—spirits pronouncing

courteous invitations to love’s table.

28

28 The first voice that flew by called out aloud:

“Vinum non habent,” and behind us that →

same voice reiterated its example.

31

31 And as that voice drew farther off, before

it faded finally, another cried:

“I am Orestes.” It, too, did not stop. →

34

34 “What voices are these, father?” were my words;

and as I asked him this, I heard a third

voice say: “Love those by whom you have been hurt.” →

37

37 And my good master said: “The sin of envy

is scourged within this circle; thus, the cords →

that form the scourging lash are plied by love.

40

40 The sounds of punished envy, envy curbed,

are different; if I judge right, you’ll hear

those sounds before we reach the pass of pardon.

43

43 But let your eyes be fixed attentively

and, through the air, you will see people seated

before us, all of them on the stone terrace.”

46

46 I opened—wider than before—my eyes;

I looked ahead of me, and I saw shades →

with cloaks that shared their color with the rocks.

49

49 And once we’d moved a little farther on,

I heard the cry of, “Mary, pray for us,” →

and then heard, “Michael,” “Peter,” and “All saints.”

52

52 I think no man now walks upon the earth

who is so hard that he would not have been

pierced by compassion for what I saw next;

55

55 for when I had drawn close enough to see

clearly the way they paid their penalty,

the force of grief pressed tears out of my eyes.

58

58 Those souls—it seemed—were cloaked in coarse haircloth;

another’s shoulder served each shade as prop,

and all of them were bolstered by the rocks:

61

61 so do the blind who have to beg appear

on pardon days to plead for what they need, →

each bending his head back and toward the other,

64

64 that all who watch feel—quickly—pity’s touch

not only through the words that would entreat

but through the sight, which can—no less—beseech.

67

67 And just as, to the blind, no sun appears,

so to the shades—of whom I now speak—here,

the light of heaven would not give itself;

70

70 for iron wire pierces and sews up

the lids of all those shades, as untamed hawks →

are handled, lest, too restless, they fly off.

73

73 It seemed to me a gross discourtesy

for me, going, to see and not be seen;

therefore, I turned to my wise counselor.

76

76 He knew quite well what I, though mute, had meant;

and thus he did not wait for my request,

but said: “Speak, and be brief and to the point.”

79

79 Virgil was to my right, along the outside,

nearer the terrace-edge—no parapet

was there to keep a man from falling off;

82

82 and to my other side were the devout

shades; through their eyes, sewn so atrociously,

those spirits forced the tears that bathed their cheeks.

85

85 I turned to them; and “You who can be certain,”

I then began, “of seeing that high light

which is the only object of your longing,

88

88 may, in your conscience, all impurity

soon be dissolved by grace, so that the stream →

of memory flow through it limpidly;

91

91 tell me, for I shall welcome such dear words,

if any soul among you is Italian;

if I know that, then I—perhaps—can help him.”

94

94 “My brother, each of us is citizen →

of one true city: what you meant to say

was ‘one who lived in Italy as pilgrim.’ ”

97

97 My hearing placed the point from which this answer

had come somewhat ahead of me; therefore,

I made myself heard farther on; moving,

100

100 I saw one shade among the rest who looked

expectant; and if any should ask how—

its chin was lifted as a blind man’s is.

103

103 “Spirit,” I said, “who have subdued yourself

that you may climb, if it is you who answered,

then let me know you by your place or name.”

106

106 “I was a Sienese,” she answered, “and

with others here I mend my wicked life,

weeping to Him that He grant us Himself.

109

109 I was not sapient, though I was called Sapia; →

and I rejoiced far more at others’ hurts

than at my own good fortune. And lest you

112

112 should think I have deceived you, hear and judge

if I was not, as I have told you, mad

when my years’ arc had reached its downward part.

115

115 My fellow citizens were close to Colle,

where they’d joined battle with their enemies,

and I prayed God for that which He had willed. →

118

118 There they were routed, beaten; they were reeling

along the bitter paths of flight; and seeing

that chase, I felt incomparable joy,

121

121 so that I lifted up my daring face

and cried to God: ‘Now I fear you no more!’— →

as did the blackbird after brief fair weather.

124

124 I looked for peace with God at my life’s end;

the penalty I owe for sin would not

be lessened now by penitence had not

127

127 one who was sorrowing for me because

of charity in him—Pier Pettinaio— →

remembered me in his devout petitions.

130

130 But who are you, who question our condition

as you move on, whose eyes—if I judge right—

have not been sewn, who uses breath to speak?”

133

133 “My eyes,” I said, “will be denied me here,

but only briefly; the offense of envy

was not committed often by their gaze.

136

136 I fear much more the punishment below; →

my soul is anxious, in suspense; already

I feel the heavy weights of the first terrace.”

139

139 And she: “Who, then, led you up here among us,

if you believe you will return below?”

And I: “He who is with me and is silent.

142

142 I am alive; and therefore, chosen spirit,

if you would have me move my mortal steps

on your behalf, beyond, ask me for that.”

145

145 “Oh, this,” she answered, “is so strange a thing

to hear: the sign is clear—you have God’s love.

Thus, help me sometimes with your prayers. I ask

148

148 of you, by that which you desire most,

if you should ever tread the Tuscan earth, →

to see my name restored among my kin.

151

151 You will see them among those vain ones who

have put their trust in Talamone (their loss →

in hope will be more than Diana cost); →

154

154 but there the admirals will lose the most.” →

Click here to go to the line

Click here to go to the line

Still the Second Terrace: the Envious. Two spirits, Guido del Duca and Rinieri da Calboli. Guido’s denunciation of the cities in the valley of the Arno, of Rinieri’s grandson, Fulcieri da Calboli, and of Romagna. Voices calling out examples of punished envy: Cain and Aglauros.

Who is this man who, although death has yet

to grant him flight, can circle round our mountain,

and can, at will, open and shut his eyes?”

4

4 “I don’t know who he is, but I do know

he’s not alone; you’re closer; question him

and greet him gently, so that he replies.”

7

7 So were two spirits, leaning toward each other, →

discussing me, along my right-hand side;

then they bent back their heads to speak to me,

10

10 and one began: “O soul who—still enclosed

within the body—make your way toward Heaven,

may you, through love, console us; tell us who

13

13 you are, from where you come; the grace that you’ve

received—a thing that’s never come to pass

before—has caused us much astonishment.”

16

16 And I: “Through central Tuscany there spreads →

a little stream first born in Falterona;

one hundred miles can’t fill the course it needs.

19

19 I bring this body from that river’s banks;

to tell you who I am would be to speak

in vain—my name has not yet gained much fame.”

22

22 “If, with my understanding, I have seized

your meaning properly,” replied to me

the one who’d spoken first, “you mean the Arno.”

25

25 The other said to him: “Why did he hide

that river’s name, even as one would do

in hiding something horrible from view?”

28

28 The shade to whom this question was addressed

repaid with this: “I do not know; but it

is right for such a valley’s name to perish,

31

31 for from its source (at which the rugged chain— →

from which Pelorus was cut off—surpasses

most other places with its mass of mountains)

34

34 until its end point (where it offers back →

those waters that evaporating skies

drew from the sea, that streams may be supplied),

37

37 virtue is seen as serpent, and all flee

from it as if it were an enemy,

either because the site is ill-starred or

40

40 their evil custom goads them so; therefore,

the nature of that squalid valley’s people

has changed, as if they were in Circe’s pasture. →

43

43 That river starts its miserable course →

among foul hogs, more fit for acorns than

for food devised to serve the needs of man.

46

46 Then, as that stream descends, it comes on curs →

that, though their force is feeble, snap and snarl;

scornful of them, it swerves its snout away. →

49

49 And, downward, it flows on; and when that ditch,

ill-fated and accursed, grows wider, it

finds, more and more, the dogs becoming wolves. →

52

52 Descending then through many dark ravines, →

it comes on foxes so full of deceit—

there is no trap that they cannot defeat.

55

55 Nor will I keep from speech because my comrade →

hears me (and it will serve you, too, to keep

in mind what prophecy reveals to me).

58

58 I see your grandson: he’s become a hunter →

of wolves along the banks of the fierce river,

and he strikes every one of them with terror.

61

61 He sells their flesh while they are still alive;

then, like an ancient beast, he turns to slaughter,

depriving many of life, himself of honor.

64

64 Bloody, he comes out from the wood he’s plundered,

leaving it such that in a thousand years

it will not be the forest that it was.”

67

67 Just as the face of one who has heard word

of pain and injury becomes perturbed,

no matter from what side that menace stirs,

70

70 so did I see that other soul, who’d turned

to listen, growing anxious and dejected

when he had taken in his comrade’s words.

73

73 The speech of one, the aspect of the other

had made me need to know their names, and I

both queried and beseeched at the same time,

76

76 at which the spirit who had spoken first

to me began again: “You’d have me do

for you that which, to me, you have refused.

79

79 But since God would, in you, have His grace glow

so brightly, I shall not be miserly;

know, therefore, that I was Guido del Duca. →

82

82 My blood was so afire with envy that, →

when I had seen a man becoming happy,

the lividness in me was plain to see.

85

85 From what I’ve sown, this is the straw I reap:

o humankind, why do you set your hearts

there where our sharing cannot have a part?

88

88 This is Rinieri, this is he—the glory, →

the honor of the house of Calboli;

but no one has inherited his worth.

91

91 It’s not his kin alone, between the Po →

and mountains, and the Reno and the coast,

who’ve lost the truth’s grave good and lost the good

94

94 of gentle living, too; those lands are full

of poisoned stumps; by now, however much

one were to cultivate, it is too late.

97

97 Where is good Lizio? Arrigo Mainardi? →

Pier Traversaro? Guido di Carpigna? →

O Romagnoles returned to bastardy!

100

100 When will a Fabbro flourish in Bologna? →

When, in Faenza, a Bernadin di Fosco,

the noble offshoot of a humble plant? →

103

103 Don’t wonder, Tuscan, if I weep when I

remember Ugolino d’Azzo, one

who lived among us, and Guido da Prata,

106

106 the house of Traversara, of Anastagi →

(both houses without heirs), and Federigo →

Tignoso and his gracious company,

109

109 the ladies and the knights, labors and leisure

to which we once were urged by courtesy

and love, where hearts now host perversity.

112

112 O Bretinoro, why do you not flee— →

when you’ve already lost your family

and many men who’ve fled iniquity?

115

115 Bagnacaval does well: it breeds no more— →

and Castrocuro ill, and Conio worse, →

for it insists on breeding counts so cursed.

118

118 Once freed of their own demon, the Pagani →

will do quite well, but not so well that any

will testify that they are pure and worthy.

121

121 Your name, o Ugolin de’ Fantolini, →

is safe, since one no longer waits for heirs

to blacken it with their degeneracy.

124

124 But, Tuscan, go your way; I am more pleased

to weep now than to speak: for that which we

have spoken presses heavily on me!”

127

127 We knew those gentle souls had heard us move →

away; therefore, their silence made us feel

more confident about the path we took.

130

130 When we, who’d gone ahead, were left alone, →

a voice that seemed like lightning as it splits

the air encountered us, a voice that said:

133

133 “Whoever captures me will slaughter me”; →

and then it fled like thunder when it fades

after the cloud is suddenly ripped through.

136

136 As soon as that first voice had granted us

a truce, another voice cried out with such

uproar—like thunder quick to follow thunder:

139

139 “I am Aglauros, who was turned to stone”; →

and then, to draw more near the poet, I

moved to my right instead of moving forward.

142

142 By now the air on every side was quiet;

and he told me: “That is the sturdy bit

that should hold every man within his limits.

145

145 But you would take the bait, so that the hook

of the old adversary draws you to him; →

thus, neither spur nor curb can serve to save you.

148

148 Heaven would call—and it encircles—you;

it lets you see its never-ending beauties;

and yet your eyes would only see the ground;

151

151 thus, He who sees all things would strike you down.”

From the Second to the Third Terrace: the Wrathful. Mid-afternoon. The Fifth Beatitude. Virgil on the sharing of heavenly goods. The Third Terrace, where Dante sees, in ecstatic vision, examples of gentleness: the Virgin Mary, Pisistratus, St. Stephen. Virgil on Dante’s vision. Black smoke.

As many as the hours in which the sphere →

that’s always playing like a child appears

from daybreak to the end of the third hour,

4

4 so many were the hours of light still left

before the course of day had reached sunset;

vespers was there; and where we are, midnight. →

7

7 When sunlight struck directly at our faces,

for we had circled so much of the mountain

that now we headed straight into the west,

10

10 then I could feel my vision overcome

by radiance greater than I’d sensed before,

and unaccounted things left me amazed;

13

13 at which, that they might serve me as a shade,

I lifted up my hands above my brow,

to limit some of that excessive splendor.

16

16 As when a ray of light, from water or →

a mirror, leaps in the opposed direction

and rises at an angle equal to

19

19 its angle of descent, and to each side

the distance from the vertical is equal,

as science and experiment have shown;

22

22 so did it seem to me that I had been

struck there by light reflected, facing me,

at which my eyes turned elsewhere rapidly.

25

25 “Kind father, what is that against which I

have tried in vain,” I said, “to screen my eyes?

It seems to move toward us.” And he replied:

28

28 “Don’t wonder if you are still dazzled by

the family of Heaven: a messenger

has come, and he invites us to ascend.

31

31 Soon, in the sight of such things, there will be

no difficulty for you, but delight—

as much as nature fashioned you to feel.”

34

34 No sooner had we reached the blessed angel

than with glad voice he told us: “Enter here;

these are less steep than were the other stairs.”

37

37 We climbed, already past that point; behind us,

we heard “Beati misericordes” sung →

and then “Rejoice, you who have overcome.”

40

40 I and my master journeyed on alone,

we two together, upward; as we walked,

I thought I’d gather profit from his words;

43

43 and even as I turned toward him, I asked:

“What did the spirit of Romagna mean

when he said, ‘Sharing cannot have a part’?”

46

46 And his reply: “He knows the harm that lies

in his worst vice; if he chastises it, →

to ease its expiation—do not wonder.

49

49 For when your longings center on things such

that sharing them apportions less to each,

then envy stirs the bellows of your sighs.

52

52 But if the love within the Highest Sphere →

should turn your longings heavenward, the fear

inhabiting your breast would disappear;

55

55 for there, the more there are who would say ‘ours,’ →

so much the greater is the good possessed

by each—so much more love burns in that cloister.”

58

58 “I am more hungry now for satisfaction,”

I said, “than if I’d held my tongue before;

I host a deeper doubt within my mind.

61

61 How can a good that’s shared by more possessors

enable each to be more rich in it

than if that good had been possessed by few?”

64

64 And he to me: “But if you still persist

in letting your mind fix on earthly things,

then even from true light you gather darkness.

67

67 That Good, ineffable and infinite, →

which is above, directs Itself toward love

as light directs itself to polished bodies.

70

70 Where ardor is, that Good gives of Itself;

and where more love is, there that Good confers

a greater measure of eternal worth.

73

73 And when there are more souls above who love,

there’s more to love well there, and they love more,

and, mirror-like, each soul reflects the other. →

76

76 And if my speech has not appeased your hunger,

you will see Beatrice—she will fulfill

this and all other longings that you feel.

79

79 Now only strive, so that the other five →

wounds may be canceled quickly, as the two

already are—the wounds contrition heals.”

82

82 But wanting then to say, “You have appeased me,”

I saw that I had reached another circle, →

and my desiring eyes made me keep still.

85

85 There I seemed, suddenly, to be caught up →

in an ecstatic vision and to see

some people in a temple; and a woman →

88

88 just at the threshold, in the gentle manner

that mothers use, was saying: “O my son,

why have you done this to us? You can see

91

91 how we have sought you—sorrowing, your father

and I.” And at this point, as she fell still,

what had appeared at first now disappeared.

94

94 Then there appeared to me another woman: →

upon her cheeks—the tears that grief distills

when it is born of much scorn for another.

97

97 She said: “If you are ruler of that city

to name which even goddesses once vied—

where every science had its source of light—

100

100 revenge yourself on the presumptuous

arms that embraced our daughter, o Pisistratus.”

And her lord seemed to me benign and mild,

103

103 his aspect temperate, as he replied:

“What shall we do to one who’d injure us

if one who loves us earns our condemnation?”

106

106 Next I saw people whom the fire of wrath →

had kindled, as they stoned a youth and kept

on shouting loudly to each other: “Kill!”

109

109 “Kill!” “Kill!” I saw him now, weighed down by death,

sink to the ground, although his eyes were bent

always on Heaven—they were Heaven’s gates—

112

112 praying to his high Lord, despite the torture,

to pardon those who were his persecutors;

his look was such that it unlocked compassion.

115

115 And when my soul returned outside itself →

and met the things outside it that are real,

I then could recognize my not false errors.

118

118 My guide, on seeing me behave as if →

I were a man who’s freed himself from sleep,

said: “What is wrong with you? You can’t walk straight;

121

121 for more than half a league now you have moved

with clouded eyes and lurching legs, as if

you were a man whom wine or sleep has gripped!”

124

124 “Oh, my kind father, if you hear me out,

I’ll tell you what appeared to me,” I said,

“when I had lost the right use of my legs.”

127

127 And he: “Although you had a hundred masks

upon your face, that still would not conceal

from me the thoughts you thought, however slight.

130

130 What you have seen was shown lest you refuse

to open up your heart unto the waters

of peace that pour from the eternal fountain.

133

133 I did not ask ‘What’s wrong with you?’ as one

who only sees with earthly eyes, which—once

the body, stripped of soul, lies dead—can’t see;

136

136 I asked so that your feet might find more force:

so must one urge the indolent, too slow

to use their waking time when it returns.”

139

139 We made our way until the end of vespers, →

peering, as far ahead as sight could stretch,

at rays of light that, although late, were bright.

142

142 But, gradually, smoke as black as night →

began to overtake us; and there was

no place where we could have avoided it.

145

145 This smoke deprived us of pure air and sight.

Click here to go to the line

Click here to go to the line

Still the Third Terrace: the Wrathful. Their sin punished by dark smoke. Marco Lombardo’s discourse on free will, on the causes of corruption, and on three worthy old men, living examples of ancient virtue.

Darkness of Hell and of a night deprived

of every planet, under meager skies,

as overcast by clouds as sky can be,

4

4 had never served to veil my eyes so thickly

nor covered them with such rough-textured stuff

as smoke that wrapped us there in Purgatory;

7

7 my eyes could not endure remaining open;

so that my faithful, knowledgeable escort

drew closer as he offered me his shoulder.

10

10 Just as a blind man moves behind his guide,

that he not stray or strike against some thing

that may do damage to—or even kill—him,

13

13 so I moved through the bitter, filthy air, →

while listening to my guide, who kept repeating:

“Take care that you are not cut off from me.”

16

16 But I heard voices, and each seemed to pray →

unto the Lamb of God, who takes away

our sins, for peace and mercy. “Agnus Dei”

19

19 was sung repeatedly as their exordium,

words sung in such a way—in unison—

that fullest concord seemed to be among them.

22

22 “Master, are those whom I hear, spirits?” I

asked him. “You have grasped rightly,” he replied,

“and as they go they loose the knot of anger.”

25

25 “Then who are you whose body pierces through

our smoke, who speak of us exactly like

a man who uses months to measure time?” →

28

28 A voice said this. On hearing it, my master →

turned round to me: “Reply to him, then ask

if this way leads us to the upward path.”

31

31 And I: “O creature who—that you return

fair unto Him who made you—cleanse yourself,

you shall hear wonders if you follow me.”

34

34 “I’ll follow you as far as I’m allowed,”

he answered, “and if smoke won’t let us see,

hearing will serve instead to keep us linked.”

37

37 Then I began: “With those same swaddling-bands →

that death unwinds I take my upward path:

I have come here by way of Hell’s exactions;

40

40 since God’s so gathered me into His grace →

that He would have me, in a manner most

unusual for moderns, see His court,

43

43 do not conceal from me who you once were,

before your death, and tell me if I go

straight to the pass; your words will be our escort.”

46

46 “I was a Lombard and I was called Marco; →

I knew the world’s ways, and I loved those goods →

for which the bows of all men now grow slack.

49

49 The way you’ve taken leads directly upward.”

So he replied, and then he added: “I

pray you to pray for me when you’re above.”

52

52 And I to him: “I pledge my faith to you

to do what you have asked; and yet a doubt

will burst in me if it finds no way out.

55

55 Before, my doubt was simple; but your statement

has doubled it and made me sure that I

am right to couple your words with another’s. →

58

58 The world indeed has been stripped utterly

of every virtue; as you said to me,

it cloaks—and is cloaked by—perversity.

61

61 Some place the cause in heaven, some, below;

but I beseech you to define the cause,

that, seeing it, I may show it to others.”

64

64 A sigh, from which his sorrow formed an “Oh,”

was his beginning; then he answered: “Brother,

the world is blind, and you come from the world.

67

67 You living ones continue to assign

to heaven every cause, as if it were

the necessary source of every motion.

70

70 If this were so, then your free will would be →

destroyed, and there would be no equity

in joy for doing good, in grief for evil.

73

73 The heavens set your appetites in motion—not →

all your appetites, but even if

that were the case, you have received both light

76

76 on good and evil, and free will, which though

it struggle in its first wars with the heavens,

then conquers all, if it has been well nurtured.

79

79 On greater power and a better nature →

you, who are free, depend; that Force engenders

the mind in you, outside the heavens’ sway.

82

82 Thus, if the present world has gone astray,

in you is the cause, in you it’s to be sought;

and now I’ll serve as your true exegete.

85

85 Issuing from His hands, the soul—on which

He thought with love before creating it—

is like a child who weeps and laughs in sport;

88

88 that soul is simple, unaware; but since →

a joyful Maker gave it motion, it

turns willingly to things that bring delight.

91

91 At first it savors trivial goods; these would

beguile the soul, and it runs after them,

unless there’s guide or rein to rule its love.

94

94 Therefore, one needed law to serve as curb;

a ruler, too, was needed, one who could →

discern at least the tower of the true city.

97

97 The laws exist, but who applies them now?

No one—the shepherd who precedes his flock →

can chew the cud but does not have cleft hooves;

100

100 and thus the people, who can see their guide

snatch only at that good for which they feel

some greed, would feed on that and seek no further.

103

103 Misrule, you see, has caused the world to be →

malevolent; the cause is clearly not

celestial forces—they do not corrupt.

106

106 For Rome, which made the world good, used to have →

two suns; and they made visible two paths—

the world’s path and the pathway that is God’s.

109

109 Each has eclipsed the other; now the sword

has joined the shepherd’s crook; the two together

must of necessity result in evil,

112

112 because, so joined, one need not fear the other:

and if you doubt me, watch the fruit and flower,

for every plant is known by what it seeds. →

115

115 Within the territory watered by →

the Adige and Po, one used to find

valor and courtesy—that is, before

118

118 Frederick was met by strife; now anyone →

ashamed of talking with the righteous or

of meeting them can journey there, secure.

121

121 True, three old men are there, in whom old times →

reprove the new; and they find God is slow

in summoning them to a better life:

124

124 Currado da Palazzo, good Gherardo, →

and Guido da Castel, whom it is better

to call, as do the French, the candid Lombard.

127

127 You can conclude: the Church of Rome confounds

two powers in itself; into the filth,

it falls and fouls itself and its new burden.”

130

130 “Good Marco,” I replied, “you reason well;

and now I understand why Levi’s sons →

were not allowed to share in legacies.

133

133 But what Gherardo is this whom you mention

as an example of the vanished people

whose presence would reproach this savage age?”

136

136 “Either your speech deceives me or would tempt me,” →

he answered then, “for you, whose speech is Tuscan,

seem to know nothing of the good Gherardo.

139

139 There is no other name by which I know him,

unless I speak of him as Gaia’s father.

God be with you; I come with you no farther.

142

142 You see the rays that penetrate the smoke →

already whitening; I must take leave—

the angel has arrived—before he sees me.”

145

145 So he turned back and would not hear me more.

From the Third to the Fourth Terrace. Examples of wrath: Procne, Haman, Amata. The angel of gentleness. The Seventh Beatitude. Ascent to the Fourth Terrace. Virgil on love and on Purgatory’s seven terraces punishing the seven sins: pride, envy, and wrath—resulting from perverted love; sloth—from defective love; avarice, gluttony, and lust—from excessive love of earthly goods.

Remember, reader, if you’ve ever been

caught in the mountains by a mist through which

you only saw as moles see through their skin, →

4

4 how, when the thick, damp vapors once begin

to thin, the sun’s sphere passes feebly through them,

then your imagination will be quick →

7

7 to reach the point where it can see how I

first came to see the sun again—when it →

was almost at the point at which it sets.

10

10 So, my steps matched my master’s trusty steps; →

out of that cloud I came, reaching the rays

that, on the shores below, by now were spent.

13

13 O fantasy, you that at times would snatch →

us so from outward things—we notice nothing

although a thousand trumpets sound around us—

16

16 who moves you when the senses do not spur you?

A light that finds its form in Heaven moves you—

directly or led downward by God’s will.

19

19 Within my fantasy I saw impressed →

the savagery of one who then, transformed,

became the bird that most delights in song;

22

22 at this, my mind withdrew to the within,

to what imagining might bring; no thing

that came from the without could enter in.

25

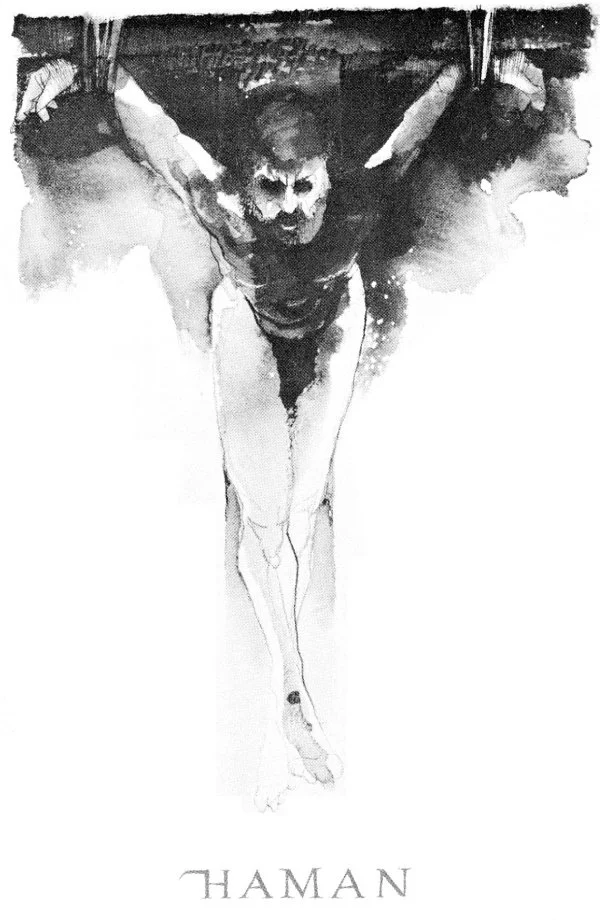

25 Then into my deep fantasy there rained

one who was crucified; and as he died, →

he showed his savagery and his disdain.

28

28 Around him were great Ahasuerus and

Esther his wife, and the just Mordecai,

whose saying and whose doing were so upright.

31

31 And when this image shattered of itself, →

just like a bubble that has lost the water

beneath which it was formed, there then rose up

34

34 in my envisioning a girl who wept →

most bitterly and said: “O queen, why did

you, in your wrath, desire to be no more?

37

37 So as to keep Lavinia, you killed

yourself; now you have lost me! I am she,

mother, who mourns your fall before another’s.”

40

40 Even as sleep is shattered when new light

strikes suddenly against closed eyes and, once

it’s shattered, gleams before it dies completely,

43

43 so my imagination fell away →

as soon as light—more powerful than light

we are accustomed to—beat on my eyes.

46

46 I looked about to see where I might be;

but when a voice said: “Here one can ascend,”

then I abandoned every other intent.

49

49 That voice made my will keen to see the one

who’d spoken—with the eagerness that cannot

be still until it faces what it wants.

52

52 But even as the sun, become too strong,

defeats our vision, veiling its own form,

so there my power of sight was overcome.

55

55 “This spirit is divine; and though unasked, →

he would conduct us to the upward path;

he hides himself with that same light he sheds.

58

58 He does with us as men do with themselves;

for he who sees a need but waits to be

asked is already set on cruel refusal.

61

61 Now let our steps accept his invitation,

and let us try to climb before dark falls—

then, until day returns, we’ll have to halt.”

64

64 So said my guide; and toward a stairway, he

and I, together, turned; and just as soon

as I was at the first step, I sensed something

67

67 much like the motion of a wing, and wind →

that beat against my face, and words: “Beati →

pacifici, those free of evil anger!”

70

70 Above us now the final rays before →

the fall of night were raised to such a height

that we could see the stars on every side.

73

73 “O why, my strength, do you so melt away?” →

I said within myself, because I felt

the force within my legs compelled to halt.

76

76 We’d reached a point at which the upward stairs →

no longer climbed, and we were halted there

just like a ship when it has touched the shore.

79

79 I listened for a while, hoping to hear

whatever there might be in this new circle;

then I turned toward my master, asking him:

82

82 “Tell me, my gentle father: what offense

is purged within the circle we have reached?

Although our feet must stop, your words need not.”

85

85 And he to me: “Precisely here, the love

of good that is too tepidly pursued

is mended; here the lazy oar plies harder.

88

88 But so that you may understand more clearly,

now turn your mind to me, and you will gather

some useful fruit from our delaying here.

91

91 My son, there’s no Creator and no creature →

who ever was without love—natural →

or mental; and you know that,” he began.

94

94 “The natural is always without error,

but mental love may choose an evil object

or err through too much or too little vigor.

97

97 As long as it’s directed toward the First Good →

and tends toward secondary goods with measure,

it cannot be the cause of evil pleasure;

100

100 but when it twists toward evil, or attends

to good with more or less care than it should,

those whom He made have worked against their Maker.

103

103 From this you see that—of necessity—love →

is the seed in you of every virtue

and of all acts deserving punishment.

106

106 Now, since love never turns aside its eyes →

from the well-being of its subject, things

are surely free from hatred of themselves;

109

109 and since no being can be seen as self-existing →

and divorced from the First Being,

each creature is cut off from hating Him.

112

112 Thus, if I have distinguished properly,

ill love must mean to wish one’s neighbor ill;

and this love’s born in three ways in your clay. →

115

115 There’s he who, through abasement of another, →

hopes for supremacy; he only longs

to see his neighbor’s excellence cast down.

118

118 Then there is one who, when he is outdone, →

fears his own loss of fame, power, honor, favor;

his sadness loves misfortune for his neighbor.

121

121 And there is he who, over injury →

received, resentful, for revenge grows greedy

and, angrily, seeks out another’s harm.

124

124 This threefold love is expiated here →

below; now I would have you understand

the love that seeks the good distortedly. →

127

127 Each apprehends confusedly a Good →

in which the mind may rest, and longs for It;

and, thus, all strive to reach that Good; but if

130

130 the love that urges you to know It or

to reach that Good is lax, this terrace, after

a just repentance, punishes for that.

133

133 There is a different good, which does not make →

men glad; it is not happiness, is not

true essence, fruit and root of every good.

136

136 The love that—profligately—yields to that →

is wept on in three terraces above us;

but I’ll not say what three shapes that loves takes—

139

139 may you seek those distinctions for yourself.”

Click here to go to the line

Click here to go to the line

The Fourth Terrace: the Slothful. Virgil on love, free will, and responsibility. Dante’s drowsiness. The Slothful shouting examples of zeal: the Virgin Mary and Caesar. The punishment of the Slothful, made to run without respite. The Abbot of San Zeno. Shouted examples of sloth: the Jews in the desert and the reluctant Trojans in Sicily.

1 comment