The great writers of our own age are, we have reason to suppose, the companions and forerunners of some unimagined change in our social condition or the opinions which cement it. The cloud of mind is discharging its collected lightning, and the equilibrium between institutions and opinions is now restoring, or is about to be restored.

As to imitation, poetry is a mimetic art. It creates, but it creates by combination and representation. Poetical abstractions are beautiful and new, not because the portions of which they are composed had no previous existence in the mind of man or in nature, but because the whole produced by their combination has some intelligible and beautiful analogy with those sources of emotion and thought, and with the contemporary condition of them: one great poet is a masterpiece of nature, which another not only ought to study but must study. He might as wisely and as easily determine that his mind should no longer be the mirror of all that is lovely in the visible universe, as exclude from his contemplation the beautiful which exists in the writings of a great contemporary. The pretence of doing it would be a presumption in any but the greatest; the effect, even in him, would be strained, unnatural, and ineffectual. A poet is the combined product of such internal powers as modify the nature of others; and of such external influences as excite and sustain these powers; he is not one, but both. Every man’s mind is, in this respect, modified by all the objects of nature and art; by every word and every suggestion which he ever admitted to act upon his consciousness; it is the mirror upon which all forms are reflected, and in which they compose one form. Poets, not otherwise than philosophers, painters, sculptors, and musicians, are, in one sense, the creators, and, in another, the creations, of their age. From this subjection the loftiest do not escape. There is a similarity between Homer and Hesiod, between Aeschylus and Euripides, between Virgil and Horace, between Dante and Petrarch, between Shakespeare and Fletcher, between Dryden and Pope; each has a generic resemblance under which their specific distinctions are arranged. If this similarity be the result of imitation, I am willing to confess that I have imitated.

Let this opportunity be conceded to me of acknowledging that I have, what a Scotch philosopher characteristically terms, ‘a passion for reforming the world’: what passion incited him to write and publish his book, he omits to explain. For my part I had rather be damned with Plato and Lord Bacon, than go to Heaven with Paley and Malthus. But it is a mistake to suppose that I dedicate my poetical compositions solely to the direct enforcement of reform, or that I consider them in any degree as containing a reasoned system on the theory of human life. Didactic poetry is my abhorrence; nothing can be equally well expressed in prose that is not tedious and supererogatory in verse. My purpose has hitherto been simply to familiarize the highly refined imagination of the more select classes of poetical readers with beautiful idealisms of moral excellence; aware that until the mind can love, and admire, and trust, and hope, and endure, reasoned principles of moral conduct are seeds cast upon the highway of life which the unconscious passenger tramples into dust, although they would bear the harvest of his happiness. Should I live to accomplish what I purpose, that is, produce a systematical history of what appear to me to be the genuine elements of human society, let not the advocates of injustice and superstition flatter themselves that I should take Aeschylus rather than Plato as my model.

The having spoken of myself with unaffected freedom will need little apology with the candid; and let the uncandid consider that they injure me less than their own hearts and minds by misrepresentation. Whatever talents a person may possess to amuse and instruct others, be they ever so inconsiderable, he is yet bound to exert them: if his attempt be ineffectual, let the punishment of an unaccomplished purpose have been sufficient; let none trouble themselves to heap the dust of oblivion upon his efforts; the pile they raise will betray his grave which might otherwise have been unknown.

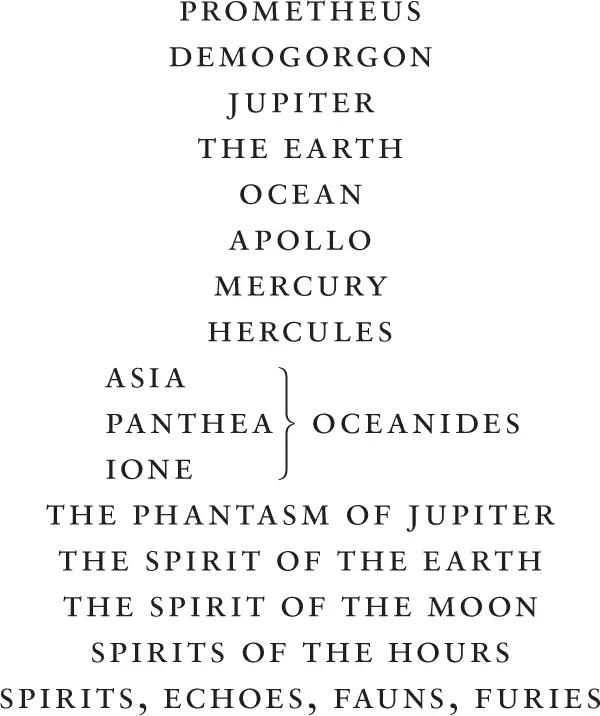

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

ACT I

Scene, a Ravine of Icy Rocks in the Indian Caucasus. PROMETHEUS is discovered bound to the precipice. PANTHEA and IONE are seated at his feet. Time, Night. During the Scene, Morning slowly breaks.

Prometheus

Monarch of Gods and Daemons, and all Spirits

But One, who throng those bright and rolling worlds

Which Thou and I alone of living things

Behold with sleepless eyes! regard this Earth

5Made multitudinous with thy slaves, whom thou

Requitest for knee-worship, prayer, and praise,

And toil, and hecatombs of broken hearts,

With fear and self-contempt and barren hope;

Whilst me, who am thy foe, eyeless in hate,

10Hast thou made reign and triumph, to thy scorn,

O’er mine own misery and thy vain revenge.

Three thousand years of sleep-unsheltered hours

And moments aye divided by keen pangs

Till they seemed years, torture and solitude,

15Scorn and despair,—these are mine empire.

More glorious far than that which thou surveyest

From thine unenvied throne, O Mighty God!

Almighty, had I deigned to share the shame

Of thine ill tyranny, and hung not here

20Nailed to this wall of eagle-baffling mountain,

Black, wintry, dead, unmeasured; without herb,

Insect, or beast, or shape or sound of life.

Ah me! alas, pain, pain ever, for ever!

No change, no pause, no hope! Yet I endure.

25I ask the Earth, have not the mountains felt?

I ask yon Heaven, the all-beholding Sun,

Has it not seen? The Sea, in storm or calm,

Heaven’s ever-changing Shadow, spread below,

Have its deaf waves not heard my agony?

30Ah me! alas, pain, pain ever, for ever!

The crawling glaciers pierce me with the spears

Of their moon-freezing crystals, the bright chains

Eat with their burning cold into my bones.

Heaven’s winged hound, polluting from thy lips

35His beak in poison not his own, tears up

My heart; and shapeless sights come wandering by,

The ghastly people of the realm of dream,

Mocking me: and the Earthquake-fiends are charged

To wrench the rivets from my quivering wounds

40When the rocks split and close again behind;

While from their loud abysses howling throng

The genii of the storm, urging the rage

Of whirlwind, and afflict me with keen hail.

And yet to me welcome is day and night,

45Whether one breaks the hoar frost of the morn,

Or starry, dim, and slow, the other climbs

The leaden-coloured east; for then they lead

Their wingless, crawling Hours, one among whom

—As some dark Priest hales the reluctant victim—

50Shall drag thee, cruel King, to kiss the blood

From these pale feet, which then might trample thee

If they disdained not such a prostrate slave.

Disdain! Ah no! I pity thee. What ruin

Will hunt thee undefended through the wide Heaven!

55How will thy soul, cloven to its depth with terror,

Gape like a Hell within! I speak in grief,

Not exultation, for I hate no more,

As then, ere misery made me wise. The curse

Once breathed on thee I would recall. Ye Mountains,

60Whose many-voiced Echoes, through the mist

Of cataracts, flung the thunder of that spell!

Ye icy Springs, stagnant with wrinkling frost,

Which vibrated to hear me, and then crept

Shuddering through India! Thou serenest Air,

65Through which the Sun walks burning without beams!

And ye swift Whirlwinds, who on poised wings

Hung mute and moveless o’er yon hushed abyss,

As thunder louder than your own made rock

The orbed world! if then my words had power,

70Though I am changed so that aught evil wish

Is dead within; although no memory be

Of what is hate—let them not lose it now!

What was that curse? for ye all heard me speak.

First Voice: from the Mountains

Thrice three hundred thousand years

75 O’er the Earthquake’s couch we stood:

Oft, as men convulsed with fears,

We trembled in our multitude.

Second Voice: from the Springs

Thunder-bolts had parched our water,

We had been stained with bitter blood,

80And had run mute, ’mid shrieks of slaughter,

Through a city and a solitude.

Third Voice: from the Air

I had clothed, since Earth uprose,

Its wastes in colours not their own,

And oft had my serene repose

85 Been cloven by many a rending groan.

Fourth Voice: from the Whirlwinds

We had soared beneath these mountains

Unresting ages; nor had thunder,

Nor yon volcano’s flaming fountains,

Nor any power above or under

90 Ever made us mute with wonder.

First Voice

But never bowed our snowy crest

As at the voice of thine unrest.

Second Voice

Never such a sound before

To the Indian waves we bore.

95A pilot asleep on the howling sea

Leaped up from the deck in agony

And heard, and cried, ‘Ah, woe is me!’

And died as mad as the wild waves be.

Third Voice

By such dread words from Earth to Heaven

100My still realm was never riven:

When its wound was closed, there stood

Darkness o’er the day like blood.

Fourth Voice

And we shrank back: for dreams of ruin

To frozen caves our flight pursuing

105Made us keep silence—thus—and thus—

Though silence is as hell to us.

The Earth

The tongueless Caverns of the craggy hills

Cried ‘Misery!’ then; the hollow Heaven replied,

‘Misery!’ And the Ocean’s purple waves,

110Climbing the land, howled to the lashing winds,

And the pale nations heard it,—‘Misery!’

Prometheus

I hear a sound of voices: not the voice

Which I gave forth. Mother, thy sons and thou

Scorn him, without whose all-enduring will

115Beneath the fierce omnipotence of Jove

Both they and thou had vanished like thin mist

Unrolled on the morning wind. Know ye not me,

The Titan? he who made his agony

The barrier to your else all-conquering foe?

120Oh, rock-embosomed lawns, and snow-fed streams,

Now seen athwart frore vapours, deep below,

Through whose o’ershadowing woods I wandered once

With Asia, drinking life from her loved eyes,

Why scorns the spirit which informs ye, now

125To commune with me? me alone, who checked—

As one who checks a fiend-drawn charioteer—

The falsehood and the force of Him who reigns

Supreme, and with the groans of pining slaves

Fills your dim glens and liquid wildernesses?

130Why answer ye not, still? Brethren!

The Earth

They dare not.

Prometheus

Who dares? For I would hear that curse again …

Ha, what an awful whisper rises up!

’Tis scarce like sound: it tingles through the frame

As lightning tingles, hovering ere it strike.

135Speak, Spirit! from thine inorganic voice

I only know that thou art moving near

And love. How cursed I him?

The Earth

How canst thou hear,

Who knowest not the language of the dead?

Prometheus

Thou art a living spirit; speak as they.

The Earth

140I dare not speak like life, lest Heaven’s fell King

Should hear, and link me to some wheel of pain

More torturing than the one whereon I roll.

Subtle thou art and good, and though the Gods

Hear not this voice, yet thou art more than God

145Being wise and kind: earnestly hearken now.

Prometheus

Obscurely through my brain, like shadows dim,

Sweep awful thoughts, rapid and thick—I feel

Faint, like one mingled in entwining love.

Yet ’tis not pleasure.

The Earth

No, thou canst not hear:

150Thou art immortal, and this tongue is known

Only to those who die …

Prometheus

And what art thou,

O melancholy Voice?

The Earth

I am the Earth,

Thy mother, she within whose stony veins,

To the last fibre of the loftiest tree

155Whose thin leaves trembled in the frozen air,

Joy ran, as blood within a living frame,

When thou didst from her bosom, like a cloud

Of glory, arise, a spirit of keen joy!

And at thy voice her pining sons uplifted

160Their prostrate brows from the polluting dust,

And our almighty Tyrant with fierce dread

Grew pale—until his thunder chained thee here.

Then—see those million worlds which burn and roll

Around us: their inhabitants beheld

165My sphered light wane in wide Heaven; the sea

Was lifted by strange tempest, and new fire

From earthquake-rifted mountains of bright snow

Shook its portentous hair beneath Heaven’s frown;

Lightning and Inundation vexed the plains;

170Blue thistles bloomed in cities; foodless toads

Within voluptuous chambers panting crawled;

When Plague had fallen on man and beast and worm,

And Famine, and black blight on herb and tree;

And in the corn, and vines, and meadow-grass,

175Teemed ineradicable poisonous weeds

Draining their growth, for my wan breast was dry

With grief; and the thin air, my breath, was stained

With the contagion of a mother’s hate

Breathed on her child’s destroyer—aye, I heard

180Thy curse, the which, if thou rememberest not,

Yet my innumerable seas and streams,

Mountains, and caves, and winds, and yon wide air,

And the inarticulate people of the dead,

Preserve, a treasured spell. We meditate

185In secret joy and hope those dreadful words,

But dare not speak them.

Prometheus

Venerable mother!

All else who live and suffer take from thee

Some comfort; flowers, and fruits, and happy sounds,

And love, though fleeting; these may not be mine.

190But mine own words, I pray, deny me not.

The Earth

They shall be told. Ere Babylon was dust,

The Magus Zoroaster, my dead child,

Met his own image walking in the garden.

That apparition, sole of men, he saw.

195For know there are two worlds of life and death:

One that which thou beholdest; but the other

Is underneath the grave, where do inhabit

The shadows of all forms that think and live

Till death unite them and they part no more;

200Dreams and the light imaginings of men,

And all that faith creates or love desires,

Terrible, strange, sublime and beauteous shapes.

There thou art, and dost hang, a writhing shade

’Mid whirlwind-shaken mountains; all the Gods

205Are there, and all the Powers of nameless worlds,

Vast, sceptred Phantoms; heroes, men, and beasts;

And Demogorgon, a tremendous Gloom;

And he, the Supreme Tyrant, throned

On burning Gold. Son, one of these shall utter

210The curse which all remember.

1 comment