The encouragement and guidance of her mother, the admiration of her siblings, and the indefatigable optimism of her father buoyed her up as much as their many dependencies weighed her down. They also provided Alcott with her great, defining subject: the delicate but durable strands of emotion and experience that join parent to child and sibling to sibling. Through and with her family, Alcott experienced the moments of sorrow, anger, frustration, and hard-won joy that she was to transform into her greatest fiction.

The life that spawned the fiction began on November 29, 1832; Louisa May Alcott was born on her father’s thirty-third birthday. Her elder sister Anna was then twenty months old. Two younger sisters—Elizabeth, known in the family as Lizzie, and Abigail, who preferred her middle name May—joined the family in 1835 and 1840. Germantown, Pennsylvania, Alcott’s birthplace, was little more than a way station for the Alcott family, though the same might be said of many of Louisa’s transitory childhood homes. Always seeking the ideal environment and often unable to pay for the places he found, Bronson Alcott moved his family dozens of times during Louisa’s childhood. Louisa’s first years were some of Bronson’s most prosperous. When Louisa was not yet three, he established a school in Boston’s Masonic Temple, where his novel approach to teaching made him, for a time, the toast of liberal New England. Believing that children possessed a unique wisdom, the elder Alcott asked his pupils as many questions as he gave answers. Challenging even very young children to think deeply about the workings of their minds and the nature of the moral universe, Bronson grasped the importance of educating the whole child—not only the intellect, but also the body and the spirit. The principles that he introduced in his school, Alcott sought to perfect in his own children’s nursery. He sought to rid his home of harsh stimuli and angry sentiments, filling it with sights and sounds that would reward his daughters’ curiosity and instill in them a love of peace and harmony. From the day that Anna and Louisa were born, Bronson, who was a compulsive diarist in his own right, kept separate journals in which he recorded every observable fact of the two girls’ development. Through these records, which eventually filled hundreds of pages, he hoped to unlock the secrets of the infant mind. He also hoped, once the girls were old enough to write for themselves, to have them continue the project through their lives, thus creating comprehensive histories of their minds from cradle to grave. Though Bronson’s scientific passion eventually cooled, the Alcott girls experienced highly scrutinized childhoods, ones marked by both careful moral restraint and aesthetic indulgence. When the guests at her birthday party outnumbered by one the available slices of cake, Louisa was required to relinquish hers to the supernumerary visitor. By contrast, when younger sister May displayed artistic talent, her parents permitted her to draw on the walls of her room. Both the strictness and the permissiveness were calculated to produce morally and intellectually exceptional children.

The Temple School in Boston, the scene of Bronson Alcott’s brightest fame—and his most crushing scandal. (Louisa May Alcott Memorial Association)

With Louisa, Bronson feared he had failed. Instead of the gentle, even-tempered girl he had hoped to create, Louisa was a willful and assertive tomboy, prone to outbursts of temper and open to every kind of innocent mischief. To all her father’s cherished theories of child rearing, she seemed the walking refutation. Despairing over her waywardness, Bronson chided the ten-year-old Louisa for her “anger, discontent, impatience [and] greedy wants.”15 For solace and encouragement, Louisa turned toward her mother, Abba, who praised her early poems as the work of a budding Shakespeare and who saw strength where her husband saw only stubbornness. “I believe,” she wrote, “there are some natures too noble to curb, too lofty to bend. Of such is my Lu.”16 For her part, Louisa thought her mother “the best woman in the world.”17

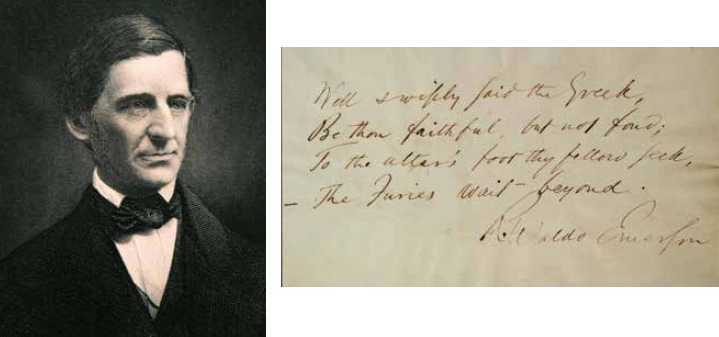

Poet and essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882) led the American Transcendentalist movement. Louisa considered him “the man who has helped me most by his life, his books, his society. I can never tell all he has been to me.” The autographed poem reads “Well and wisely said the Greek, / Be thou faithful but not fond; / To the altar’s foot thy fellow seek, / The Furies wait beyond.” (From the collection of the editor)

The Alcotts settled in Concord not once but three times: from 1840 to 1843, then from 1845 to 1848, and finally in 1857. In 1858, they moved into the home Bronson christened Orchard House, where they remained until 1877. It was in Concord that Louisa came to know her father’s close friends Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, as well as a somewhat less warm acquaintance, Nathaniel Hawthorne.

1 comment