Emerson shared his library with Louisa. Thoreau took her and her sisters on nature walks and boating expeditions. It was a girlhood of intellectual riches. It was also an early life of grinding poverty. Convinced of the evil of the moneymaking world, Bronson intended, by his Spartan example, to persuade his daughters of the unimportance of money. To the contrary, a long history of meager meals and patched clothing taught Louisa that money mattered very much indeed. She taught; she sewed; she hired herself out for housework—anything to bring in an extra dollar. From the age of eighteen, she noted in her journal every scrap of income that came her way. Even after the success of Little Women brought her all the money she had ever imagined, she would drive herself relentlessly to write for pay. In her mind, made all too sensitive by early deprivations, no amount of security was ever enough.

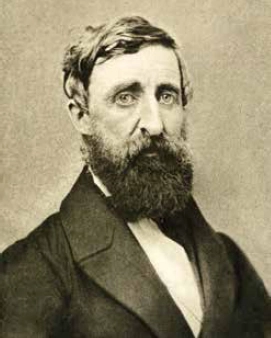

Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862), the author of Walden and “Civil Disobedience,” showed Alcott the sanctity of the natural world. When he died, she wrote, “Though he didn’t go to church he was a better Christian than many who did.” (Louisa May Alcott Memorial Association)

Perhaps the defining episode of Alcott’s childhood began with high hopes on an overcast day in June 1843 and ended the following January in snow and shattered hopes. The seven-month interval in between witnessed the rise, decline, and fall of her father’s boldest social experiment, the communal farm he called Fruitlands. The idea for Fruitlands first came to Alcott on a visit to England in 1842. With encouragement and a financial subsidy from Emerson, he had gone at the invitation of a group of reformers who were so taken with the American’s educational theories that they had christened their experimental school “Alcott House.” While there, Bronson forged a friendship with Charles Lane, a disaffected financial journalist who had concluded that the existing society had become all but hopeless in its moral corruption. Together with Henry Wright, another visionary at Alcott House, Bronson and Lane conceived of a “new plantation in America” that would undo society’s wrongs and supply a model for the world’s renewal.18 The community would do away with money and private property. It would also rigorously exclude any products that, like cotton and sugar, were produced by slave labor. Though these ideas were radical enough in the 1840s, Alcott and his friends extended their moral purity further still. They and their followers would also benefit their animal brethren by abstaining from consuming meat, fish, milk, and eggs and by shunning all other animal products as well: they would abide no silk, no woolen garments, no leather in their shoes. To many, the reformers’ extremism seemed laughable. Yet it was hard to justly criticize the purity of their goal: to live life in a way that caused no pain to any living creature.

One final indispensable tenet of Bronson Alcott’s vision for his utopia was to exert an especially strong influence on ten-year-old Louisa. He meant to do away with the idea of the traditional family, replacing it with a concept he and Lane called “consociate family.” The theory called upon all the community’s members to cast aside their personal preferences for their spouses and blood relations and to form a single, egalitarian family, in which no person could make a special claim on the love or loyalty of any other. The goal, Alcott told his wife, was to make each member “emancipated from the bonds of self and made free in the freedom of love.”19

Louisa idolized her mother, Abigail May Alcott (1800–1877) and observed that she “always did what came to her in the way of duty and charity, and let pride, taste, and comfort suffer for love’s sake.” (Louisa May Alcott Memorial Association)

Alcott brought Lane, Lane’s young son William, and Wright back to America with him in October 1842. On the first morning of the following June, now minus the wayward Mr. Wright, who had fallen in love with a lady reformer and was now pursuing his own private paradise, the Alcotts and the Lanes took possession of a farm the two men had purchased (or, as they would have said, liberated from the bonds of worldly commerce) a small distance from Harvard, Massachusetts. Hamstrung by its excessive love of virtue, Fruitlands never secured a firm footing. At its peak, its population, including the six Alcotts and two Lanes, never crested fifteen. As summer turned to autumn, the membership began to dwindle. More eager to enlist more members than to make the best of what they had, Bronson and Lane frequently departed the commune on generally barren recruiting junkets, leaving most of the crushing task of running the farm to Mrs. Alcott and the children. Asked whether the farm employed any beasts of burden, Abba replied, “Only one woman.”20

By December, no one but the Alcotts and Lanes remained.

1 comment