(Louisa May Alcott Memorial Association)

Alcott’s own great success was now much nearer than she dreamed. In May 1868, Bronson Alcott got in touch with Thomas Niles. The elder Alcott had himself been working on a book of philosophical observations that he called “Tablets,” and he was looking for a publisher. The two men thought it might be a clever stratagem to bring out Bronson’s book and something by Louisa at the same time. Bronson proposed that she could write a book of fairy stories. Niles was not excited by that prospect; he still wanted his girls’ book. With this nudge from Niles and her father, Alcott set to work on a manuscript she called Little Women. Abba, Anna, and May all warmed to the idea of a novel based on the domestic adventures of the Alcott girls from twenty years before, but Alcott herself remained halfhearted. She grumbled to her journal, “I plod away, though I don’t enjoy this sort of thing. Never liked girls, or knew many, except my sisters; but our queer plays and experiences may prove interesting, though I doubt it.”81 She wrote a dozen chapters before the end of June, intending, as she later confessed, to prove to Niles that she could not write a worthy book for girls. She thought the chapters dull, and Niles at first agreed. Then Niles showed the partial manuscript to his niece, who laughed over them until she cried. Sensing that he might have a great success on his hands, he urged Alcott on. Alcott flung herself into the drafting of ten more chapters and fell into one of her creative vortices. She emerged, exhausted, on July 15 with an aching head and 402 manuscript pages—the first twenty-two chapters of Little Women. Part First of the book was virtually complete. It read better than Alcott had expected: the authenticity of the story, so much of it derived from the Alcotts’ actual lives, had worked wonders. By now, the effort had become a family project: Alcott’s sister May prepared four drawings to illustrate the book. Though Alcott was satisfied with both the story and the artwork, she worried that the engravers might “spoil the pictures & make Meg cross-eyed, Beth with no nose, or Jo with a double chin.”82 Niles, for his part, was after a larger fish. Reading the manuscript over, he was now certain that the book would “ ‘hit,’ which means I think it will sell well.” He wanted Alcott to add just one more chapter “in which allusions might be made to something in the future,” namely, a sequel.83 Alcott promptly obliged, dashing off Chapter XXIII, “Aunt March Settles the Question,” which she ended with the teaser, “So grouped the curtain falls on Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy. Whether it ever rises again, depends upon the reception given to the first act of the domestic drama, called ‘LITTLE WOMEN.’ ”

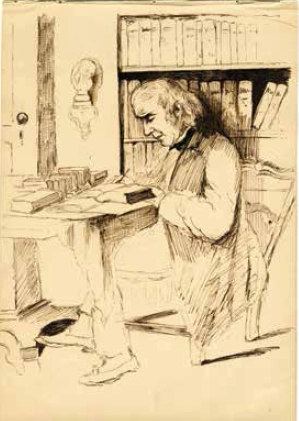

Bronson Alcott in his study, as sketched by his daughter May. (Louisa May Alcott Memorial Association)

Astonishing coincidences bound Bronson and Louisa May Alcott together. They shared a birthday, November 29, and another strange alignment was to take place at the end of their lives. But now, within weeks of each other in the fall of 1868, Alcott père and Alcott fille each achieved the greatest literary breakthrough of their lives: Bronson with Tablets and Louisa with Part First of Little Women. Tablets sold briskly and was, in Louisa’s words “much admired,” but it was Little Women that caused the publishing sensation. As Niles had predicted, Alcott’s book for girls was an instant success. The first edition sold out before the end of October, and forty-five hundred copies were in print by the year’s end. Niles pressed at once for the second volume, and Alcott began work on November 1, resolving to write a chapter a day and be finished before the month was out. She wrote “like a steam engine” and very nearly kept up with her self-imposed schedule, completing thirteen chapters by the seventeenth.84 Her thirty-sixth birthday came on the twenty-ninth. She spent it “alone, writing hard.”85 Though her pace then slowed, she managed to send Part Second to Roberts Brothers on New Year’s Day 1869.

The greatest problem she had faced in writing Part Second involved neither time nor energy but a conflict as to content.

1 comment