While some especially pious readers had taken offense at the March sisters’ staging a play on Christmas, Alcott shrugged that criticism off. A complaint that irritated Alcott much more deeply appeared time and again in the torrent of fan letters inspired by Part First. Alcott lamented, “Girls write to ask who the little women will marry, as if that was the only end and aim of a woman’s life.”86 Her adoring public seemed particularly bent on seeing Jo paired off with Laurie, and the prospect infuriated her. She defiantly declared, “I won’t marry Jo to Laurie to please any one.”87 Indeed, it was her preference that Jo “should have remained a literary spinster.”88 She was not to have her way. Fearing the public response if Jo March stayed single, Roberts Brothers insisted that the character must marry someone. Alcott fulminated to her mother’s brother, Samuel May: “Publishers are very perwerse [sic] & wont let authors have thier [sic] way, so my little women must grow up & be married off in a very stupid style.”89 But Alcott could be stubborn, too. By way of a reluctant compromise, she “out of perversity went & made a funny match” for Jo, and Professor Bhaer was born. Alcott fully expected her sequel to “disappoint or disgust most readers.” In return for her having refused to give Jo to Laurie, she calmly predicted, “I expect vials of wrath to be poured out upon my head, but rather enjoy the prospect.” 90

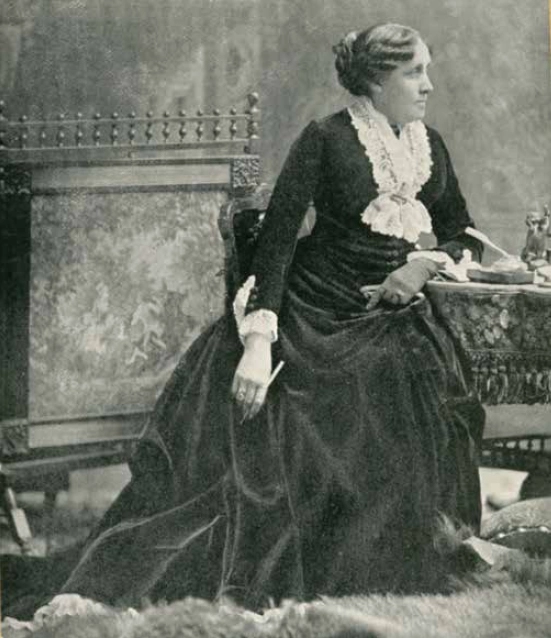

Alcott around the age of forty, in Gilded Age finery. (Louisa May Alcott Memorial Association)

The wrath, however, did not come. What came instead were book orders, seemingly without end. By the end of 1869, some twenty thousand copies of Part First and eighteen thousand of Part Second had been printed, and that was only the beginning. From 1868 to 1882, the trade edition of Part First was to go through sixty-seven printings. Over the same period, Part Second went through sixty-five. On the wise advice of Niles, Alcott had kept the copyrights to both volumes in her own name. If the decision did not make her exorbitantly wealthy, it at least assured that she and the other Alcotts would live in comfort for the rest of their lives. A few words of context are appropriate. In 1870, a farmworker in Massachusetts was doing slightly better than average if he earned $20 a month with board. A carpenter was above the median for his profession if he took home $3 a day.91 In that year, Alcott reported receiving $2,500 in royalties for Little Women, an amount that more than tripled the following year. In January 1872, Roberts Brothers paid her $4,400—six months’ worth of royalties from the books she had written for the company, which now included An Old-Fashioned Girl and Little Men. Crowing over her success in 1870, Niles hailed Alcott as a “magician, or rather . . . the good genius who answers all the rubbings of the magic lamp.”92

Alcott’s sister Anna declared in 1871, “Now she has made her pot of gold she can rest forever.”93 But Alcott did not rest. Having driven herself so long to write and earn money for her family, she seemed incapable of stopping—and equally unable to grasp that superhuman efforts were no longer required to keep poverty at bay. She kept writing, often to the brink of exhaustion, turning her adventures, as she put it, “into bread and butter.”94 With irrepressible satisfaction, she mused, “Twenty years ago I resolved to make the family independent if I could. At forty that is done.”95 But her health remained precarious, and the loss of privacy that fame brought with it wore upon her sensitive nerves. “I asked for bread,” she complained, “and got a stone—in the shape of a pedestal.”96 Reporters sat on the wall of Orchard House and took notes. Artists sketched her in her garden. The intrusions were so constant and annoying that she sometimes climbed out the back window to escape them. To those who told her to accept fame as a blessing, her advice was terse. “Let ’em try it.”97

Louisa May Alcott at the pinnacle of her success.

1 comment