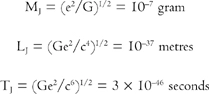

For the velocity of light he used an average of existing measurements, c = 3 × 108 metres per second; for Newton's gravitation constant he used the value obtained by John Herschel, G = 0.67 × 10–11 m3 Kg–1s–2, and for his unit of ‘electrine’ charge he used e = 10–20 Ampères.38 Here are the unusual new units that he found, in terms of the constants e, c and G, and in terms of grams, metres and seconds:

These are extraordinary quantities. Although a mass of 10–7 gram is not too outlandish, similar to that of a speck of dust, Stoney's units of length and time were unlike any that had been encountered by scientists before. They were fantastically, almost inconceivably, small. There was (and still is) no possibility of measuring such lengths and times directly. In a way, that is what one might have expected. These units are deliberately not constructed from human dimensions, for human convenience, or for human utility. They are defined by the very fabric of physical reality that determines the nature of light, electricity and gravity. They don't care about us.

Stoney had succeeded brilliantly in his quest for a superhuman system of units. But, alas, they attracted little attention. There was no practical use for his ‘natural’ units and their significance was hidden to everyone, even Stoney himself, who was more interested in promoting his electron up until its discovery in 1897. Natural units needed to be discovered all over again.

MAX PLANCK'S NATURAL UNITS

‘Science cannot solve the ultimate mystery of nature. And that is because, in the last analysis, we ourselves are part of the mystery that we are trying to solve.’

Max Planck39

Stoney's idea was rediscovered in a slightly different form by the German physicist Max Planck, in 1899. Planck is one of the most important physicists of all time. He discovered the quantum nature of energy that launched the quantum revolution in our understanding of the world and provided the first correct description of heat radiation (the so called ‘Planck spectrum’) and has one of the fundamental constants of Nature named after him. He was a central figure in physics of his time, won the Nobel prize for physics in 1918, and died in 1947 aged 89. A quiet, unassuming man, he was deeply religious40 and greatly admired by his younger contemporaries, like Einstein and Bohr.

Planck's conception of Nature placed great emphasis upon its intrinsic rationality and independence of human thought. He believed in an intelligence behind the appearances which fixed the nature of reality. Our most fundamental conceptions of Nature needed to be aware of the need to identify that deep structure which was far from the needs of human utility and convenience. In the last year of his life he was asked by a former student if he believed that the quest to unite all the constants of Nature by some deeper theory was appealing. He replied with enthusiasm, tempered by realism about the difficulty of the challenge:

‘As to your question about the connections between the universal constants, it is without doubt an attractive idea to link them together as closely as possible by reducing these various constants to a single one. I for my part, however, am doubtful that this will be successful. But I may be mistaken.’41

Unlike Einstein, Planck did not really believe in any attainable all-encompassing theory of physics which would explain all the constants of Nature. For if such a theory arrived then physics would cease to be an inductive science. Others, like Pierre Duhem and Percy Bridgman, regarded the promised Planckian separation of scientific description from human conventions as unattainable in principle, viewing the constants of Nature and the theoretical descriptions that they underpin entirely as artefacts of a particular human choice of representation to make sense of what was seen.

Planck was suspicious of attributing fundamental significance to quantities that had been created as a result of the ‘accident’ of our situation:

‘All the systems of units that have hitherto been employed, including the so-called absolute C. G. S. system [centimetre, gram and second, for measuring length, mass and time], owe their origin to the coincidence of accidental circumstances, inasmuch as the choice of the units lying at the base of every system has been made, not according to general points of view which would necessarily retain their importance for all places and all times, but essentially with reference to the special needs of our terrestrial civilization …

Thus the units of length and time were derived from the present dimensions and motion of our planet, and the units of mass temperature from the density and the most important temperature points of water, as being the liquid which plays the most important part on the surface of the earth, under a pressure which corresponds to the mean properties of the atmosphere surrounding us. It would be no less arbitrary if, let us say, the invariable wave length of Na-light were taken as unit of length. For, again, the particular choice of Na from among the many chemical elements could be justified only, perhaps, by its common occurrence on the earth, or by its double line, which is in the range of our vision, but is by no means the only one of its kind. Hence it is quite conceivable that at some other time, under changed external conditions, every one of the systems of units which have so far been adopted for use might lose, in part or wholly, its original natural significance.’

Instead, he wanted to see the establishment of

‘units of length, mass, time and temperature which are independent of special bodies or substances, which necessarily retain their significance for all times and for all environments, terrestrial and human or otherwise’.42

Whereas Stoney had seen a way of cutting the Gordian knot of subjectivity in the choice of practical units, Planck used his special units to underpin a non-anthropomorphic basis for physics and ‘which may, therefore, be described as “natural units”.’ The progressive revelation of this basis was for him the hallmark of real progress towards as far-reaching a separation as possible of the phenomena in the external world from those in human consciousness.

In accord with his universal outlook, in 1899 Planck proposed43 that natural units of mass, length and time be constructed from the most fundamental constants of Nature: the gravitation constant G, the speed of light c, and the constant of action, h, which now bears Planck's name.44 Planck's constant determines the smallest amount by which energy can be changed (the ‘quantum’).

1 comment