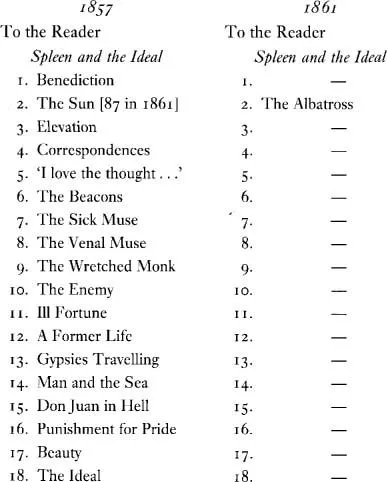

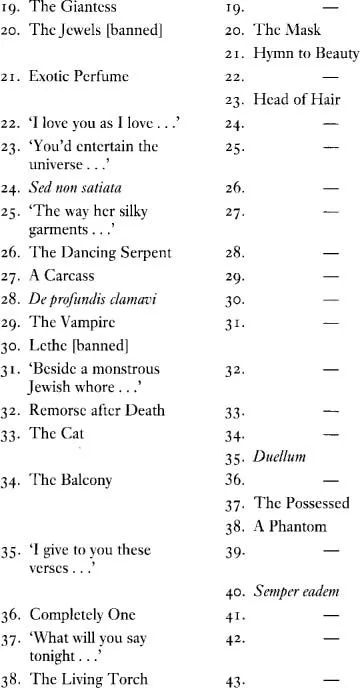

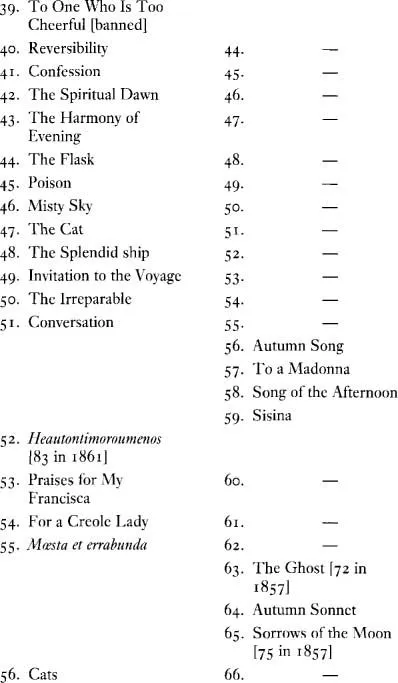

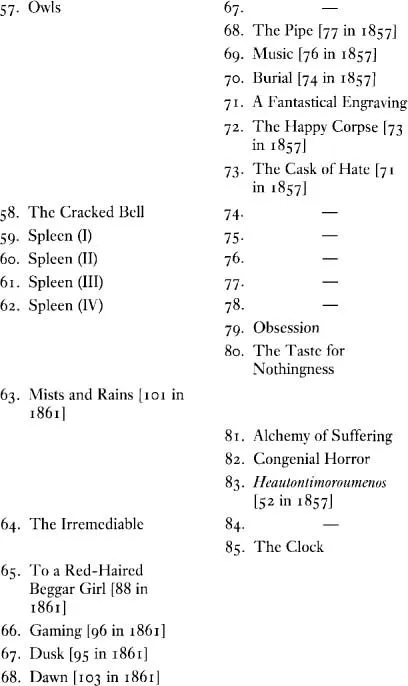

This procedure has the advantage of enriching the sections to which these six poems belong and of preventing readers from considering them above all as poems that were banned. The table below indicates which are the poems added in 1861, where they were inserted, and where poems from the 1857 edition were arranged differently in 1861.

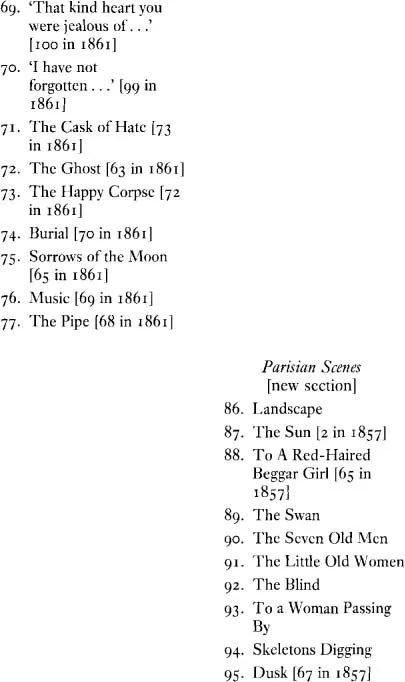

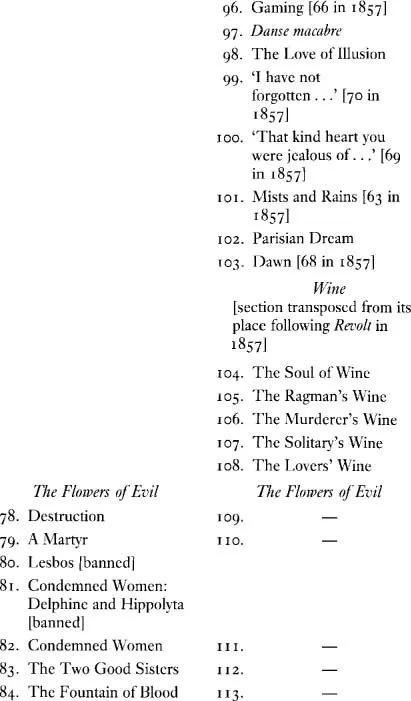

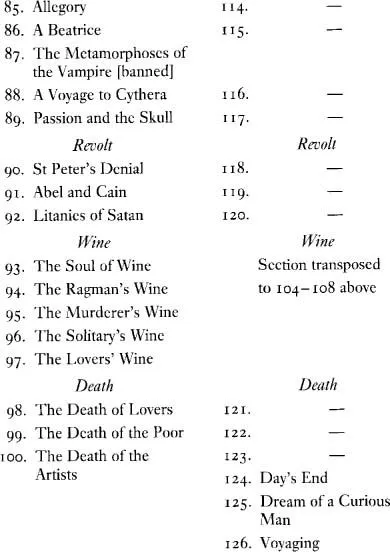

Arrangement of Poems in the First Two Editions of ‘Les Fleurs du Mal’

A dash (—) in the 1861 column indicates that the poem listed on the same line in the 1857 column appears here in 1861. Poems whose names appear in the 1861 list are new, unless their former place in the 1857 edition is indicated in brackets.

The 1861 edition of The Flowers of Evil, which we are reprinting here, brought four major changes.

(1) A new section was added: ‘Parisian Scenes’ (Tableaux parisiens). This section not only contains what are now some of Baudelaire’s most celebrated poems, such as ‘The Swan’, ‘The Seven Old Men’, and ‘The Little Old Women’; its intense yet ironical engagement with urban life and its phantasmagoria today seems quintessentially Baudelairian, the soul of The Flowers of Evil.

(2) Thirteen poems were removed from the end of ‘Spleen and the Ideal’, where they had formed something of a miscellany, and were placed as appropriate: in ‘Parisian Scenes’, among the poems about or addressed to women in the middle of ‘Spleen and the Ideal’, or among the poems about the poet’s meditations which follow the poems to and about women. This rearrangement, together with the insertion at the end of ‘Spleen and the Ideal’ of a number of poems about self-torment and the oppressions of life, gave this section a different, more intense ending—indeed, a climax that had been lacking in 1857.

(3) The rearrangement and the addition of new love poems gave this part of ‘Spleen and the Ideal’ a new diversity, in the sorts of amorous relations conceived.

(4) The section ‘Wine’ was moved from its place just before ‘Death’ in 1857 to follow the new ‘Parisian Scenes’ in 1861, so that emphasis came to fall less on wine as an escape and prelude to death and more on the diverse characters of the city—ragpickers, murderers, lovers, artists—whose lives wine touches.

Critics agree that the 1861 edition is a stronger collection, not only because of the new poems, but because of the rearrangement Baudelaire produced.

Later in the 1860s, Baudelaire wished to publish a further edition of The Flowers of Evil as part of a collected edition of his works but had not succeeded in negotiating arrangements with a publisher before he fell ill. In 1865 Baudelaire and Poulet-Malassis decided to reprint the banned poems along with some others in Belgium, where books banned in France were often published. Les Épaves de Charles Baudelaire (‘Charles Baudelaire’s Waifs’ or ‘Cast-offs’) appeared in 1866. The cover claimed that it was published in Amsterdam ‘At the Sign of the Cock’ but it was actually printed by Poulet-Malassis in Brussels. An unsigned Editor’s Note stated: ‘This collection consists of poems, for the most part banned or unpublished, which Mr. Charles Baudelaire did not wish to place in the definitive edition of The Flowers of Evil.’ The note also claimed that the collection was published without the author’s knowledge, by a friend to whom he had given the poems and who wished to share his pleasure in them.

The Waifs contained twenty-three poems, including the six banned poems (grouped together as poems II–VII under the heading ‘Banned Poems Taken from The Flowers of Evil’) and ‘Praises for My Francisca’, which in fact appeared in every edition of The Flowers of Evil. We print the other sixteen poems in the order in which they appeared.

After Baudelaire’s death in 1867, his friends Charles Asselineau and Théodore de Banville undertook to produce a new edition of the poems for the complete works, to be published by Michel Lévy. This volume, the third edition of The Flowers of Evil, appeared in 1868. In producing this edition, Asselineau and Banville used a copy of the 1861 edition in which Baudelaire himself had inserted eleven further poems. It is not known for certain which poems these were, much less where Baudelaire would have liked to have had them inserted, if indeed he had made any such decision (in 1867, when Michel Lévy visited Baudelaire during his illness and expressed a wish to begin publishing the complete works straight away, Baudelaire, though he could not speak, made it clear by gestures, pointing to dates in a diary, that he wanted Levy to wait three months—presumably in the hope that he would have recovered and could have a hand in the arrangement).1 In addition to these eleven poems, Asselineau and Banville decided to add further poems as well, some of which scarcely seem to belong to The Flowers of Evil, to a total of twenty-five: they reprinted twelve poems from The Waifs, despite the explicit statement there that these were poems Baudelaire did not see fit to include in The Flowers of Evil, a poem to Banville himself (‘To Théodore de Banville’), a translation from Longfellow’s Song of Hiawatha (which we have omitted), and an ‘Epigraph for a Condemned Book’. We print the eleven new poems along with ‘To Théodore de Banville’ and ‘Epigraph for a Condemned Book’ as ‘Additional Poems from the Third Edition of The Flowers of Evil’.

In the 1868 edition of The Flowers of Evil, twenty of the twenty-five additional poems were placed by Asselineau and Banville together in a group towards the end of ‘Spleen and the Ideal’, between no. 82, ‘Congenial Horror’, and no. 83, ‘Heautontimoroumenos’. The other five were inserted as follows (I have marked with an asterisk those eleven poems which, by best critical estimates, Baudelaire might have wished to include):

‘To Théodore de Banville’, after no. 15, ‘Don Juan in Hell’

‘Poem on the Portrait of Honoré Daumier’, after no. 59,

‘Sisina’

‘Lola de Valence’ and ‘The Insulted Moon’* in ‘Parisian

Scenes’ after no. 87, ‘The Sun’

‘Epigraph for a Condemned Book’ at the beginning of the

‘Flowers of Evil’ section, before no. 109, ‘Destruction’.

The order of the other twenty poems in the 1868 edition is as follows (after ‘Congenial Horror’, no. 82): ‘The Peacepipe, after Longfellow’; ‘Prayer of a Pagan’;* ‘The Pot Lid’;* ‘The Unforeseen’; ‘Midnight Examination’;* ‘Sad Madrigal’;* ‘The Cautioner’;* ‘To a Girl of Malabar’; ‘The Voice’; ‘Hymn’; ‘The Rebel’;* ‘Bertha’s Eyes’; ‘The Fountain’; ‘The Ransom’; ‘Very Far from France’;* The Setting of the Romantic Sun’; ‘On Tasso in Prison, by Eugéne Delacroix’; ‘The Gulf’;* ‘Lament of an Icarus’;* ‘Meditation’.*

1 Charles Asselineau, Biography of Baudelaire, in Jacques Crépet and Claude Pichois, eds. Baudelaire el Asselineau (Paris: Nizet, 1953), 148–9.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

PROSE WRITINGS OF BAUDELAIRE

Most of Baudelaire’s prose has been translated into English. The following list of editions is not exhaustive:

The Prose Poems and La Fanfarlo, trans. Rosemary Lloyd (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), a companion volume to this in the World’s Classics series.

Intimate Journals, trans. Christopher Isherwood (London: Methuen, 1949); My Heart Laid Bare and Other Prose Writings, trans. Norman Cameron (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1950).

The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays, trans. Jonathan Mayne (London: Phaidon Press, 1955).

Art in Paris, 1845–1862: Salons and Other Exhibitions Reviewed by Charles Baudelaire, trans. Jonathan Mayne (London: Phaidon Press, 1965).

Selected Writings on Art and Artists, trans.

1 comment