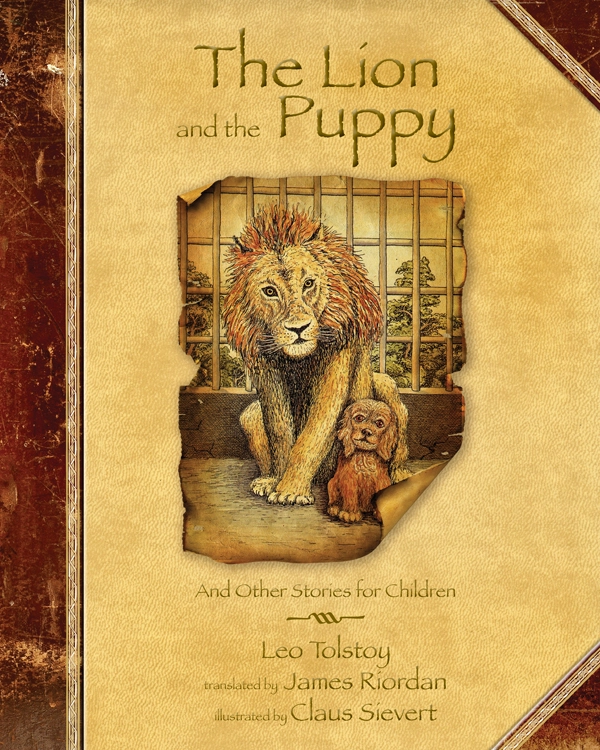

The Lion and the Puppy

Copyright © 1988, 2012 by Leo Tolstoy

Translation copyright © James Riordan 1988, 2012

Illustrations copyright © 1988, 2012 Claus Sievert

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written

consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries

should be addressed to Sky Pony Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Sky Pony Press books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifcations. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Sky Pony Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY

10018 or [email protected].

Sky Pony® is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyponypress.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Manufactured in China, September 2011 This product conforms to CPSIA 2008

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-61608-484-4

CONTENTS

Introduction

Translator’s Note

The Lion and the Puppy

Little Cottontop

Escape of a Dancing Bear

Masha and the Mushrooms.

Death of a Bird-Cherry Tree

Little Philip Who Wanted to Go to School

A Young Boy’s Story of How a Storm Caught Him in the Forest

The King and the Shirt

Two Brothers Learn a Lesson

A Young Boy’s Story of How He Found Queen Bees for His Granddad

The Tired Swan

The Old Fire-Dog

Two Merchants

The Old Poplar

How Many Geese Make Six?

The “Dead” Man and the Bear

The Litde Bird

The Plum Stone

Better to Be Lean and Free than Plump and Chained

A Young Boy’s Story of How He Did Not Go to Town

Dew upon the Grass

Uncle Jacob’s Dog

Why Wolves Are Mean and Squirrels Frisky

The Ants

From an Acorn Grew an Oak Tree Tall

INTRODUCTION:

LEO TOLSTOY — STORIES FOR CHILDREN

Do you know the story of the Selfish Giant who was never visited by Spring until he opened up his garden to children? Here is a true story about a Russian nobleman who not only let children into the garden of his great country home, he also taught them to read and write. He even wrote the stories in this book for them.

And well he might. For he was one of the greatest storytellers that ever lived, a giant among authors.

His name was Leo Tolstoy.

This is how he came to write his stories for children.

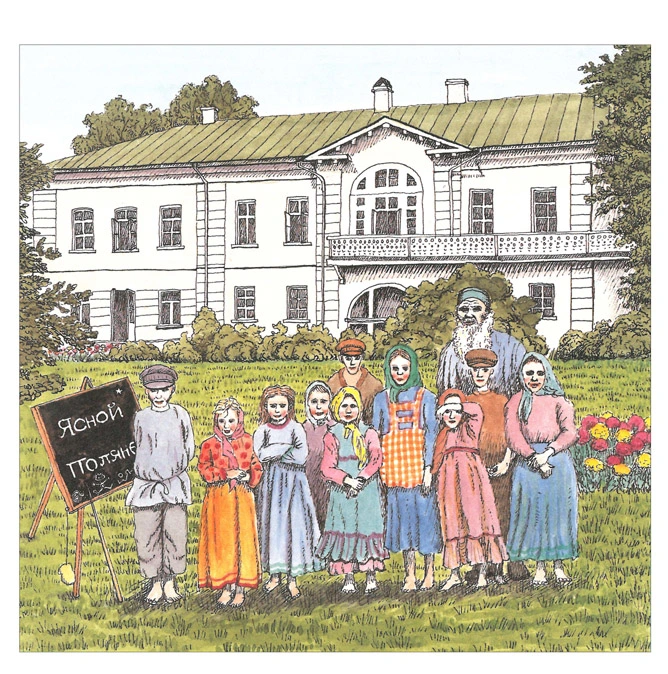

Many years ago, in Russia, behind a big stone wall, there was a beautiful garden with soft green grass and glades of silver birch. The village children were not allowed into this garden. All they could see as they peered through the tall Iron railings of the gate was a distant lake shimmering through the trees beyond a neatly swept drive of stately poplars. And somewhere in the grounds of that great garden, they knew, there stood a big house in which a famous gentleman lived.

The notice on the gates said “Yasnaya Polyana,” which in Russian means “Clear Glades.”

CLEAR GLADES

Country House of Count L. N. Tolstoy

That was plain enough. The children knew they had to keep out.

How surprised — and not a little afraid — they were when one day they heard that the Count had summoned them to his mansion. The word soon spread through the village. What did he want them for? Rumor had it that he wanted to teach them to read and write.

What a strange idea!

In those days there were few enough schools in the towns, fewer still in the countryside. “Very, very rarely could a villager read or write. If a letter needed to be written, people went to the deacon and had to pay a tidy sum for it. There were no books in the village, no newspapers, no schools.

Yet now it seemed that the Count had a mind to open a school for poor children. And to teach them himself.

The children were shy But on the appointed day they put on their Sunday best — a clean shirt and fresh birch-bark shoes — smoothed down their unkempt hair with yellow sunflower oil or brown rye juice, and set off in a crowd for the Big House.

The year was 1849. The gold and russet trees of autumn had laid a crisp carpet of leaves along the drive, as the children made their way to the house. Once past the dark, still waters of the lake, a big house suddenly came into view, set back behind the trees. The tall two-story building seemed like a palace to boys and girls who had grown up in squat smoke-begrimed huts under straw-thatched roofs. Nervously, the knots of village children stood before the house, waiting for the Count to appear.

Finally he appeared on the veranda — a tall, broad-shouldered figure with long straggly hair, a large fleshy nose, and a bushy black beard. As he fixed them with his fierce stare, from under the most enormous eyebrows, the children drew back in alarm. Yet the moment he smiled and spoke, their shyness seemed to melt away

The school at Clear Glades was open all day long, and children could come and go as they pleased. No one forced them to attend, and no one forced any lessons upon them. Each child did whatever took her or his fancy — drawing, reading, writing, sports. And, by all accounts, the children came to the school very willingly, some arriving as early as seven in the morning and staying until late evening. Such was their eagerness to learn.

But it was not all sitting at desks. Tolstoy loved games.

1 comment