The Metamorphosis

CONTENTS

Cover

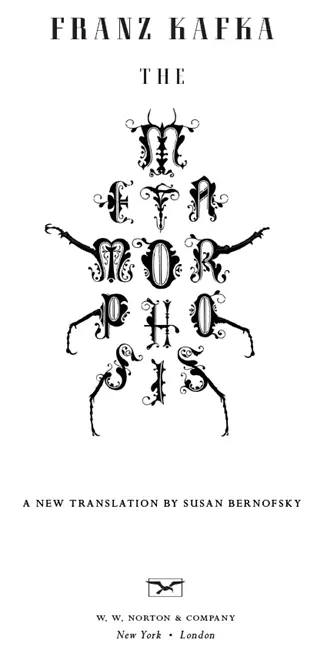

Title Page

Introduction: The Beetle and the Fly, by David Cronenberg

THE METAMORPHOSIS

Afterword: The Death of a Salesman, by Susan Bernofsky

Advance praise for THE METAMORPHOSIS

Copyright

Also by Susan Bernofsky

INTRODUCTION

THE BEETLE AND THE FLY

David Cronenberg

I woke up one morning recently to discover that I was a seventy-year-old man. Is this different from what happens to Gregor Samsa in The Metamorphosis? He wakes up to find that he’s become a near-human-sized beetle (probably of the scarab family, if his household’s charwoman is to be believed), and not a particularly robust specimen at that. Our reactions, mine and Gregor’s, are very similar. We are confused and bemused, and think that it’s a momentary delusion that will soon dissipate, leaving our lives to continue as they were. What could the source of these twin transformations possibly be? Certainly, you can see a birthday coming from many miles away, and it should not be a shock or a surprise when it happens. And as any well-meaning friend will tell you, seventy is just a number. What impact can that number really have on an actual, unique physical human life?

In the case of Gregor, a young traveling salesman spending a night at home in his family’s apartment in Prague, awakening into a strange, human/insect hybrid existence is, to say the obvious, a surprise he did not see coming, and the reaction of his household—mother, father, sister, maid, cook—is to recoil in benumbed horror, as one would expect, and not one member of his family feels compelled to console the creature by, for example, pointing out that a beetle is also a living thing, and turning into one might, for a mediocre human living a humdrum life, be an exhilarating and elevating experience, and so what’s the problem? This imagined consolation could not, in any case, take place within the structure of the story, because Gregor can understand human speech, but cannot be understood when he tries to speak, and so his family never think to approach him as a creature with human intelligence. (It must be noted, though, that in their bourgeois banality, they somehow accept that this creature is, in some unnamable way, their Gregor. It never occurs to them that, for example, a giant beetle has eaten Gregor; they don’t have the imagination, and he very quickly becomes not much more than a housekeeping problem.) His transformation seals him within himself as surely as if he had suffered a total paralysis. These two scenarios, mine and Gregor’s, seem so different, one might ask why I even bother to compare them. The source of the transformations is the same, I argue: we have both awakened to a forced awareness of what we really are, and that awareness is profound and irreversible; in each case, the delusion soon proves to be a new, mandatory reality, and life does not continue as it did.

Is Gregor’s transformation a death sentence or, in some way, a fatal diagnosis? Why does the beetle Gregor not survive? Is it his human brain, depressed and sad and melancholy, that betrays the insect’s basic sturdiness? Is it the brain that defeats the bug’s urge to survive, even to eat? What’s wrong with that beetle? Beetles, the order of insect called Coleoptera, which means “sheathed wing” (though Gregor never seems to discover his own wings, which are presumably hiding under his hard wing casings), are notably hardy and well adapted for survival; there are more species of beetle than any other order on earth. Well, we learn that Gregor has bad lungs—they are “none too reliable”—and so the Gregor beetle has bad lungs as well, or at least the insect equivalent, and perhaps that really is his fatal diagnosis; or perhaps it’s his growing inability to eat that kills him, as it did Kafka, who ultimately coughed up blood and died of starvation caused by laryngeal tuberculosis at the age of forty. What about me? Is my seventieth birthday a death sentence? Of course, yes, it is, and in some ways it has sealed me within myself as surely as if I had suffered a total paralysis. And this revelation is the function of the bed, and of dreaming in the bed, the mortar in which the minutiae of everyday life are crushed, ground up, and mixed with memory and desire and dread. Gregor awakes from troubled dreams which are never directly described by Kafka. Did Gregor dream that he was an insect, then awake to find that he was one? “‘What in the world has happened to me?’ he thought.” “It was no dream,” says Kafka, referring to Gregor’s new physical form, but it’s not clear that his troubled dreams were anticipatory insect dreams. In the movie I co-wrote and directed of George Langelaan’s short story The Fly, I have our hero Seth Brundle, played by Jeff Goldblum, say, while deep in the throes of his transformation into a hideous fly/human hybrid, “I’m an insect who dreamt he was a man and loved it. But now the dream is over, and the insect is awake.” He is warning his former lover that he is now a danger to her, a creature with no compassion and no empathy. He has shed his humanity like the shell of a cicada nymph, and what has emerged is no longer human. He is also suggesting that to be a human, a self-aware consciousness, is a dream that cannot last, an illusion. Gregor too has trouble clinging to what is left of his humanity, and as his family begins to feel that this thing in Gregor’s room is no longer Gregor, he begins to feel the same way. But unlike Brundle’s fly self, Gregor’s beetle is no threat to anyone but himself, and starves and fades away like an afterthought as his family revels in their freedom from the shameful, embarrassing burden that he has become.

When The Fly was released in 1986, there was much conjecture that the disease that Brundle had brought on himself was a metaphor for AIDS. Certainly I understood this—AIDS was on everybody’s mind as the vast scope of the disease was gradually being revealed. But for me, Brundle’s disease was more fundamental: in an artificially accelerated manner, he was aging. He was a consciousness that was aware that it was a body that was mortal, and with acute awareness and humor participated in that inevitable transformation that all of us face, if only we live long enough. Unlike the passive and helpful but anonymous Gregor, Brundle was a star in the firmament of science, and it was a bold and reckless experiment in transmitting matter through space (his DNA mixes with that of an errant fly) that caused his predicament.

Langelaan’s story, first published in Playboy magazine in 1957, falls firmly within the genre of science fiction, with all the mechanics and reasonings of its scientist hero carefully, if fancifully, constructed (two used telephone booths are involved). Kafka’s story, of course, is not science fiction; it does not provoke discussion regarding technology and the hubris of scientific investigation, or the use of scientific research for military purposes. Without sci-fi trappings of any kind, The Metamorphosis forces us to think in terms of analogy, of reflexive interpretation, though it is revealing that none of the characters in the story, including Gregor, ever does think that way. There is no meditation on a family secret or sin that might have induced such a monstrous reprisal by God or the Fates, no search for meaning even on the most basic existential plane. The bizarre event is dealt with in a perfunctory, petty, materialistic way, and it arouses the narrowest range of emotional response imaginable, almost immediately assuming the tone of an unfortunate natural family occurrence with which one must reluctantly contend.

Stories of magical transformations have always been part of humanity’s narrative canon.

1 comment