You don’t mind the smell of strong tobacco, I hope?”44

Baker Street, ca. 1895.

Round London (1896)

“I always smoke ‘ship’s’ myself,”45 I answered.

“That’s good enough. I generally have chemicals about, and occasionally do experiments. Would that annoy you?”

“By no means.”

“Let me see—what are my other shortcomings? I get in the dumps at times, and don’t open my mouth for days on end. You must not think I am sulky when I do that. Just let me alone, and I’ll soon be right. What have you to confess now? It’s just as well for two fellows to know the worst of one another before they begin to live together.”

I laughed at this cross-examination. “I keep a bull pup,”46 I said, “and I object to rows because my nerves are shaken, and I get up at all sorts of ungodly hours, and I am extremely lazy. I have another set of vices when I’m well,47 but those are the principal ones at present.”

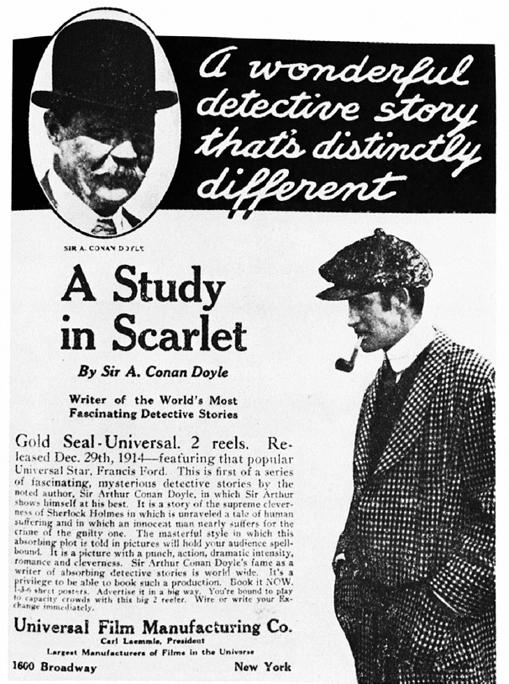

Poster for A Study in Scarlet.

(United States: Gold Seal/Universal Film Mfg. Co., 1914)

“Do you include violin-playing in your category of rows?” he asked, anxiously.

“It depends on the player,” I answered. “A well-played violin is a treat for the gods—a badly-played one—”

“Oh, that’s all right,” he cried, with a merry laugh.48 “I think we may consider the thing as settled—that is, if the rooms are agreeable to you.”

“When shall we see them?”

“Call for me here at noon to-morrow, and we’ll go together and settle everything,” he answered.

“All right—noon exactly,” said I, shaking his hand.

We left him working among his chemicals, and we walked together towards my hotel.

“By the way,” I asked suddenly, stopping and turning upon Stamford, “how the deuce did he know that I had come from Afghanistan?”

My companion smiled an enigmatical smile. “That’s just his little peculiarity,” he said. “A good many people have wanted to know how he finds things out.”

“Oh! a mystery is it?” I cried, rubbing my hands. “This is very piquant. I am much obliged to you for bringing us together. “ ‘The proper study of mankind is man,’49 you know.”

“You must study him, then,” Stamford said, as he bade me good-bye. “You’ll find him a knotty problem, though. I’ll wager he learns more about you than you about him. Good-bye.”

“Good-bye,” I answered, and strolled on to my hotel, considerably interested in my new acquaintance.

2 Watson’s middle initial appears in the Sherlock Holmes Canon only three times: at the foot of the sketch plan illustrating “The Priory School” (in the Strand Magazine for February 1904); on the lid of the tin box at Cox’s Bank (“Thor Bridge”); and here. Dorothy L. Sayers, in her classic article “Dr. Watson’s Christian Name,” argues that the “H” stands for “Hamish,” a Scotch equivalent to “James” (see “Man with the Twisted Lip” for an instance in which Watson’s wife refers to him as “James”). Several other scholars propose “Henry,” owing primarily to high contemporary regard for John Henry Newman (1801– 1890), the cardinal who helped found the Oxford movement by attempting to incorporate Roman Catholic practices into the Church of England. Still others, for varied but ultimately unconvincing reasons, propose “Hampton,” “Harrington,” “Hector,” “Horatio,” “Hubert,” “Huffham,” and even “Holmes.” Only fragments of the manuscript of A Study in Scarlet are extant, consisting of one page of notes for the story and a four-line excerpt from a notebook, reproduced here. The page of notes reveals that Dr. Watson originally considered using the pseudonyms Sherrinford Holmes and Ormond Sacker (the latter for himself). Whether the names he eventually used are the parties’ real names is a subject beyond the scope of this work. See this editor’s “What Do We Really Know About Sherlock Holmes and John H. Watson?”

3 Army surgeon-majors and surgeons were attached to regiments and corps, or served as executive officers in the hospitals. Every battalion in India had one surgeon-major and two surgeons. An appointment as a surgeon brought a starting rank as a lieutenant; six years’ full-pay service qualified the practitioner as a captain.

1 comment