There is no mention in the Canon of Watson’s rank, but his title would have been Acting Surgeon (the Assistant Surgeon title was abolished in 1872) and his pay grade that of a lieutenant.

Windsor Magazine Christmas Number (1895).

Artist unknown

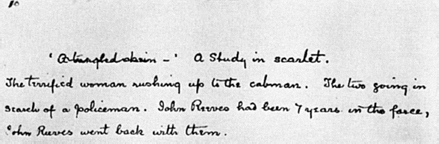

Notes for A Study in Scarlet.

4 Edgar W. Smith proposes, in “A Bibliographical Note,” that Watson’s “reminiscences” were originally published privately in 1885 or so; and that in addition to the material reprinted as A Study in Scarlet, they covered “an assortment of the doctor’s earlier writings.” These may have included Watson’s experiences with women “extending over many nations and three separate continents” (The Sign of Four) and further details of his experiences in India. “There was much he had to say,” Smith concludes, “… being the man he was.”

Bliss Austin concurs with the notion that Watson’s reminiscences were printed prior to their inclusion in A Study in Scarlet. He goes on to argue that they served as the basis for Watson’s meeting Arthur Conan Doyle, who was to serve a pivotal role in the doctor’s literary career. In his autobiography Memories and Adventures, Austin points out, Conan Doyle may well have been thinking of Watson when he wrote, “My pleasant recollection of those days from 1880 to 1893 lay in my first introduction, as a more or less rising author, to the literary life of London.” Among the authors he noted meeting were “Rudyard Kipling, James Stephen Phillips, Watson … and a whole list of others.”

Yet not everyone agrees that “reprint” necessarily signifies a previous printing. John Ball, for one, concludes, in “The Second Collaboration,” that the reminiscences were never published at all but that this statement was Conan Doyle’s way of recognising Watson’s co-authorship of the work (Conan Doyle, Ball deduces, wrote “The Country of the Saints”—see note 241, below).

5 In order to receive his M.D., Watson would have first had to acquire membership in the Royal College of Surgeons and a licence from the Royal College of Physicians, according to Michael Harrison’s The London of Sherlock Holmes. The latter two qualifications were essential for Watson to open his own medical practice; the M.D. degree, however, indicates that Watson continued his education past the normal medical degree, the M.B. (equivalent to the American M.D.), in pursuit of his interests. In Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson: A Medical Digression, Maurice Campbell surmises that Watson received his Bachelor of Medicine (M.B., B.S.—a prerequisite for the M.D. degree) in 1876 from St. Bartholomew’s Hospital Medical College (see note 28, below). Robert S. Katz, M.D., in “Doctor Watson—A Physician of Mediocre Qualifications?,” points out that the British M.D. degree is conditioned on presentation of a thesis of outstanding merit and concludes that Watson wrote his thesis on neuropathology, a remarkable achievement in light of the fledgling nature of the field in 1878.

6 When London’s first university college was founded in Bloomsbury in 1828, its mission was—at least in part—to make higher education available to non-Anglicans, who were at that time barred from attending Oxford and Cambridge. “It was a true London institution,” writes Peter Ackroyd in London: The Biography, “its founders comprising radicals, Dissenters, Jews and utilitarians.” (Historian Roy Porter reports that critics scorned it as “that godless institution in Gower Street.”) The college’s educational philosophy, too, differed fundamentally from that of Oxford and Cambridge: the goal of what became known as University College was to produce practising doctors and engineers, not scholars and theologians. A second London college, King’s College, was founded in 1829 by members of the Anglican church; and in 1836, the University of London was formed as an administrative entity designed to examine and confer degrees upon students from both institutions. That jurisdiction was broadened by the Supplemental Charter of 1849, which allowed students from anywhere in the British Empire to earn degrees from the University of London. In 1878—the year Watson earned his degree—the university became the first in the United Kingdom to grant degrees to women, and in fact had been educating women at its London School of Medicine for Women since 1874. The university did not begin offering its own courses until 1900. There is no indication of where Watson actually studied.

Watson’s course of study likely followed along lines similar to those pursued by Dr. Arthur Conan Doyle, when he studied at the University of Edinburgh from 1876 to 1881. In his Memories and Adventures, Conan Doyle describes his course of study as “one long weary grind at botany, chemistry, anatomy, physiology and a whole list of compulsory subjects, many of which have a very indirect bearing upon the art of curing. The whole system of teaching, as I look back upon it, seems far too oblique and not nearly practical enough for the purpose in view.” Students learned surgery by observing operations from seats in tiers encircling an operating table. Basic laboratory techniques were also studied, and the fortunate had the benefit of instructors like Dr. Joseph Bell, who could teach the art of diagnosis (see note 1, above). Conan Doyle took employment during his school years as a medical assistant (which required no qualifications), both for the money and the practical experience.

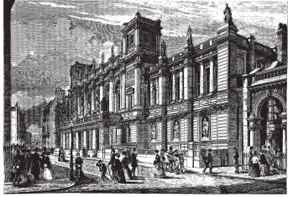

“The London University Building, Burlington Gardens,” by Pennethorne.

Graphic (1870)

Conan Doyle’s living experience, however, may have been markedly different from Watson’s. Conan Doyle found the University of Edinburgh to be “more practical than most other colleges,” he wrote, “since there is none of the atmosphere of an enlarged public school, as is the case in English Universities, but the student lives a free man in his own rooms with no restrictions of any sort.” Where Watson lived during these years is unknown.

7 The Royal Victoria Military Hospital at Netley (now the site of the Royal Victoria Country Park) was opened in 1863 thanks largely to the efforts of Florence Nightingale, whose experiences in the Crimean War inspired her to fight for better medical treatment for wounded soldiers. Lytton Strachey, in his seminal Emininent Victorians, recounts that Nightingale frequently butted heads in this mission with Fox Maule Ramsay, Lord Panmure (known as “the Bison”), the secretary of state for war from 1855 to 1858 and a man, according to Strachey, who was conservative and ambivalent about making any major changes in the established medical order.

1 comment