Lord Panmure supervised construction of the new hospital while Nightingale was out of the country, and she returned to find the plans unacceptable—outdated and adhering to notions of hospital care that she had hoped to reform. Despite her personal appeal to Lord Palmerston, Lord Panmure stood his ground, and construction proceeded apace; “and so,” Strachey writes, “the chief military hospital in England was triumphantly completed on unsanitary principles, with unventilated rooms, and with all the patients’ windows facing northeast.”

8 The prescribed course at Netley consisted of six months’ study of military surgery, military medicine, hygiene, and pathology. Two sessions or courses were given each year, one beginning in April, the other in October, for candidates who passed an entrance examination. Elliot Kimball, in Dr. John H. Watson at Netley, establishes that Watson took the course beginning in October 1879 and terminating in March 1880, having spent the time between June 1878 and October 1879 travelling on the Continent for personal reasons.

9 Created in 1674, the 5th Regiment of Foot—also known as the Fifth Foot, the Fighting Fifth, and the Old and Bold Fifth—became the 5th (Northumberland) Regiment of Fusiliers in 1836, its members serving in the Indian Mutiny and the Second Afghan War. The regiment was renamed as the Northumberland Fusiliers in 1881.

10 The Second Afghan War (1878–1880) was one of three conflicts in which Britain tried to exert control over Afghanistan, a region considered extremely valuable for its northern proximity to India. Further complicating matters was the concern that Russia was gaining greater influence in central Asia, thus posing a threat to British imperialism there. It was an anxiety held most deeply by the viceroy of India, Edward Robert Bulwer-Lytton, future 1st Earl of Lytton (a diplomat and sometime poet whose father, Edward George Earle Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Baron of Lytton, penned the famous “It was a dark and stormy night,” the first words of the opening sentence of his 1830 novel Paul Clifford). When the emir of Afghanistan, Sher Ali, received a Russian diplomatic mission in Kabul and refused to do likewise for the British, Lytton interpreted the emir’s actions as hostile and called for military maneuvers. “The usual British invasion,” writes Simon Schama in A History of Britain, “was followed by the equally time-honoured local uprising and wholesale slaughter of the British mission, which as usual required a second, punitive campaign—in this case punitive for the British in the losses of both men and money.” Victory was achieved and certain areas of Afghanistan ceded to Britain, but the war’s heavy cost (including the murder of a British envoy at Kabul) helped turn public opinion against the government’s increasingly jingoistic tendencies.

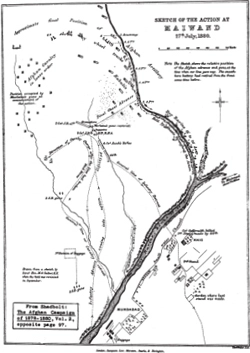

The charge at Maiwand.

11 Also spelled Kandahar or Qandahar, the city was established as the capital of Afghanistan in 1747. It was occupied by the British during the First Afghan War (1839– 1842) and from 1879 to 1881.

12 The Berkshires, officially Princess Charlotte of Wales’s (Berkshire) Regiment, was formed in 1881 from the former 49th and 66th Infantry Regiments. The 66th Foot, as it was known, fought at Maiwand, but by the time Watson wrote up his account (and perhaps by the time he was retired) the Regiment had been incorporated into the Berkshires, and Watson uses the then-current name here.

13 The village of Maiwand, fifty miles from Kandahar, was the scene of a horrific battle that took place on July 27, 1880. The conflict began after Ayub Khan, the governor of Herat and a son of Sher Ali, advanced upon Kandahar with a contingent of 25,000 men. His intent was to displace Sher Ali’s nephew, Abdur-Rahman Khan, now installed as the British-approved emir. General George Burrows and the 66th Infantry Regiment set out to intercept Ayub with the understanding that aid would come from some 6,000 Afghan tribesmen who had been armed by the British. But when the tribesmen defected to join Ayub, the general was left with 2,500 British soldiers to face a force of 25,000 Afghans. “When the enemy cavalry cleared the front,” wrote Captain Mosley Mayne, of the 3rd Cavalry, “we were able to see indistinctly masses and masses of men. Due to the haze it was only when they moved about that we could distinguish them as men and not a dense forest.” Burrows’s forces were routed, and Ayub occupied Maiwand until Sir Frederick Roberts arrived from Kabul with a force of 10,000 to retake the area. Walter Richards, historian of the British Army in India, writes, “There is no grimmer story in all the war annals of the country; no names shine in her honour-roll with more brilliant lustre than do those of the officers and men of the 66th who died in that wild day of terror and ruin on the fatal ridge of Maiwand.”

“There I was struck on the shoulder by a bullet.”

Geo. Hutchinson, A Study in Scarlet (London: Ward, Lock Bowden, and Co., 1891)

14 Watson’s report here of a wounded shoulder contradicts his testimony—in The Sign of Four and elsewhere—of a wounded leg. In “The Noble Bachelor,” for example, Watson mentions that “the Jezail bullet which I had brought back in one of my limbs” forces him to sit with his legs propped up on a chair, and in The Sign of Four, he describes himself as seated “nursing my wounded leg. I had had a jezail bullet through it some time before.” W. B. Hepburn, in “The Jezail Bullet,” reaches the logical conclusion that Watson was wounded twice, but many other scholars ingeniously attempt to explain how two wounds could have been caused by one bullet only. Alvin Rodin and Jack Key, in Medical Casebook of Doctor Arthur Conan Doyle, suggest that Watson may have been bent over a patient when shot, with the bullet passing through Watson’s shoulder and leg. Similarly, Peter Brain proposes that Watson was shot from below while squatting over a cliff to answer a call of nature. Others hypothesise that a single bullet may have ricocheted off the bone, grazed the artery, left the body at an acute angle, and then entered the leg, while several physician-scholars point out that the bullet may have passed along the subclavian artery and lodged in a place remote from the entry wound. Julian Wolff, however, concludes that Watson deliberately misrepresented the site of the wound so as to avoid mentioning the actual, embarrassing site: his groin.

Sketch of the action at Maiwand on July 27, 1880.

15 Although the original text is “Jezail,” the correct form of the word is “jezail,” not capitalised, referring not to an Afghan tribe but to a type of gun. Whether this is a printer’s error or the author’s is unclear.

1 comment