This perfection has in no instance been attained – but is unquestionably attainable. ›Smile on such,‹ the dactyl, is incorrect, because ›such,‹ from the character of the two consonants ch, cannot easily be enunciated in the ordinary time of a short syllable, which its position declares that it is. Almost every reader will be able to appreciate the slight difficulty here; and yet the error is by no means so important as that of the ›And,‹ in the spondee. By dexterity we may pronounce ›such‹ in the true time; but the attempt to remedy the rhythmical deficiency of the ›And‹ by drawing it out, merely aggravates the offence against natural enunciation, by directing attention to the offence.

My main object, however, in quoting these lines, is to show that, in spite of the prosodies, the length of a line is entirely an arbitrary matter. We might divide the commencement of Byron's poem thus:

Know ye the | land where the |

or thus:

Know ye the | land where the | cypress and |

or thus:

Know ye the | land where the | cypress and | myrtle are |

or thus:

Know ye the | land where the | cypress and | myrtle are | emblems of |

In short, we may give it any division we please, and the lines will be good – provided we have at least two feet in a line. As in mathematics two units are required to form number, so rhythm (from the Greek aritmos, number) demands for its formation at least two feet. Beyond doubt, we often see such lines as

Know ye the –

Land where the –

lines of one foot; and our prosodies admit such; but with impropriety: for common-sense would dictate that every so obvious division of a poem as is made by a line, should include within itself all that is necessary for its own comprehension; but in a line of one foot we can have no appreciation of rhythm, which depends upon the equality between two or more pulsations. The false lines, consisting sometimes of a single cæsura, which are seen in mock Pindaric odes, are of course ›rhythmical‹ only in connection with some other line; and it is this want of independent rhythm which adapts them to the purposes of burlesque alone. Their effect is that of incongruity (the principle of mirth), for they include the blankness of prose amid the harmony of verse.

My second object in quoting Byron's lines, was that of showing how absurd it often is to cite a single line from amid the body of a poem, for the purpose of instancing the perfection or imperfection of the line's rhythm. Were we to see by itself

Know ye the land where the cypress and myrtle,

we might justly condemn it as defective in the final foot, which is equal to only three, instead of being equal to four, short syllables.

In the foot ›flowers ever‹ we shall find a further exemplification of the principle of the bastard iambus, bastard trochee, and quick trochee, as I have been at some pains in describing these feet above. All the Prosodies on English Verse would insist upon making an elision in ›flowers,‹ thus ›flow'rs,‹ but this is nonsense. In the quick trochee ›many are the‹ occurring in Mr. Cranch's trochaic line, we had to equalize the time of the three syllables ›any, are, the‹ to that of the one short syllable whose position they usurp. Accordingly each of these syllables is equal to the third of a short syllable – that is to say, the sixth of a long. But in Byron's dactylic rhythm, we have to equalize the time of the three syllables ›ers, ev, er‹ to that of the one long syllable whose position they usurp, or (which is the same thing) of the two short. Therefore, the value of each of the syllables ›ers, ev, and er‹ is the third of a long. We enunciate them with only half the rapidity we employ in enunciating the three final syllables of the quick trochee – which latter is a rare foot. The ›flowers ever‹ on the contrary, is as common in the dactylic rhythm as is the bastard trochee in the trochaic, or the bastard iambus in the iambic. We may as well accent it with the curve of the crescent to the right, and call it a bastard dactyl. A bastard anapæst, whose nature I now need be at no trouble in explaining, will of course occur, now and then, in an anapæstic rhythm.

In order to avoid any chance of that confusion which is apt to be introduced in an essay of this kind by too sudden and radical an alteration of the conventionalities to which the reader has been accustomed, I have thought it right to suggest for the accent marks of the bastard trochee, bastard iambus, etc., etc., certain characters which, in merely varying the direction of the ordinary short accent (), should imply, what is the fact that the feet themselves are not new feet, in any proper sense, but simply modifications of the feet, respectively, from which they derive their names. Thus a bastard iambus is, in its essentiality, – that is to say, in its time, – an iambus. The variation lies only in the distribution of this time. The time, for example, occupied by the one short (or half of long) syllable, in the ordinary iambus, is, in the bastard, spread equally over two syllables, which are accordingly the fourth of long.

But this fact – the fact of the essentiality, or whole time, of the foot being unchanged – is now so fully before the reader that I may venture to propose, finally, an accentuation which shall answer the real purpose – that is to say, what should be the real purpose of all accentuation – the purpose of expressing to the eye the exact relative value of every syllable employed in Verse.

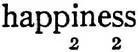

I have already shown that enunciation, or length, is the point from which we start. In other words, we begin with a long syllable. This, then, is our unit; and there will be no need of accenting it at all. An unaccented syllable, in a system of accentuation, is to be regarded always as a long syllable. Thus a spondee would be without accent. In an iambus, the first syllable being ›short,‹ or the half of long, should be accented with a small 2, placed beneath the syllable; the last syllable, being long, should be unaccented: the whole would be thus (control). In a trochee, these accents would be merely conversed, thus ( ). In a dactyl, each of the two final syllables, being the half of long, should, also, be accented with a small 2 beneath the syllable; and, the first syllable left unaccented, the whole would be thus (

). In a dactyl, each of the two final syllables, being the half of long, should, also, be accented with a small 2 beneath the syllable; and, the first syllable left unaccented, the whole would be thus ( ).

).

1 comment