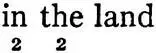

In an anapæst we should converse the dactyl, thus ( ). In the bastard dactyl, each of the three concluding syllables being the third of long, should be accented with a small 3 beneath the syllable, and the whole foot would stand thus (

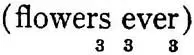

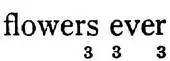

). In the bastard dactyl, each of the three concluding syllables being the third of long, should be accented with a small 3 beneath the syllable, and the whole foot would stand thus ( ). In the bastard anapæst we should converse the bastard dactyl, thus (

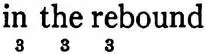

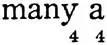

). In the bastard anapæst we should converse the bastard dactyl, thus ( ). In the bastard iambus, each of the two initial syllables, being the fourth of long, should be accented below with a small 4; the whole foot would be thus (

). In the bastard iambus, each of the two initial syllables, being the fourth of long, should be accented below with a small 4; the whole foot would be thus ( ). In the bastard trochee we should converse the bastard iambus, thus (

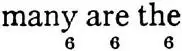

). In the bastard trochee we should converse the bastard iambus, thus ( ). In the quick trochee, each of the three concluding syllables, being the sixth of long, should be accented below with a small 6; the whole foot would be thus (

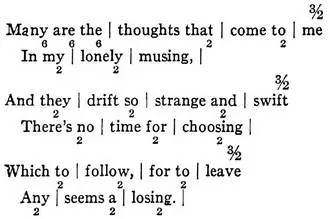

). In the quick trochee, each of the three concluding syllables, being the sixth of long, should be accented below with a small 6; the whole foot would be thus (  ). The quick iambus is not yet created, and most probably never will be, for it will be excessively useless, awkward, and liable to misconception, – as I have already shown that even the quick trochee is, – but, should it appear, we must accent it by conversing the quick trochee. The cæsura, being variable in length, but always longer than ›long,‹ should be accented above, with a number expressing the length or value of the distinctive foot of the rhythm in which it occurs. Thus a cæsura, occurring in a spondaic rhythm, would be accented with a small 2 above the syllable, or, rather, foot. Occurring in a dactylic or anapæstic rhythm, we also accent it with the 2, above the foot. Occurring in an iambic rhythm, however, it must be accented, above, with 11/2, for this is the relative value of the iambus. Occurring in the trochaic rhythm, we give it, of course, the same accentuation. For the complex 11/2, however, it would be advisable to substitute the simpler expression, 3/2, which amounts to the same thing.

). The quick iambus is not yet created, and most probably never will be, for it will be excessively useless, awkward, and liable to misconception, – as I have already shown that even the quick trochee is, – but, should it appear, we must accent it by conversing the quick trochee. The cæsura, being variable in length, but always longer than ›long,‹ should be accented above, with a number expressing the length or value of the distinctive foot of the rhythm in which it occurs. Thus a cæsura, occurring in a spondaic rhythm, would be accented with a small 2 above the syllable, or, rather, foot. Occurring in a dactylic or anapæstic rhythm, we also accent it with the 2, above the foot. Occurring in an iambic rhythm, however, it must be accented, above, with 11/2, for this is the relative value of the iambus. Occurring in the trochaic rhythm, we give it, of course, the same accentuation. For the complex 11/2, however, it would be advisable to substitute the simpler expression, 3/2, which amounts to the same thing.

In this system of accentuation Mr. Cranch's lines, quoted above, would thus be written:

In the ordinary system the accentuation would be thus:

Many are the | thoughts that | come to | me

In my | lonely | musing, |

And they | drift so | strange and | swift |

There's no | time for | choosing |

Which to | follow, | for to | leave

Any | seems a | losing. |

It must be observed here that I do not grant this to be the ›ordinary‹ scansion. On the contrary, I never yet met the man who had the faintest comprehension of the true scanning of these lines, or of such as these. But granting this to be the mode in which our prosodies would divide the feet, they would accentuate the syllables as just above.

Now, let any reasonable person compare the two modes. The first advantage seen in my mode is that of simplicity – of time, labor, and inksaved. Counting the fractions as two accents, even, there will be found only twenty-six accents to the stanza. In the common accentuation there are forty-one. But admit that all this is a trifle, which it is not, and let us proceed to points of importance. Does the common accentuation express the truth in particular, in general, or in any regard? Is it consistent with itself? Does it convey either to the ignorant or to the scholar a just conception of the rhythm of the lines? Each of these questions must be answered in the negative. The crescents, being precisely similar, must be understood as expressing, all of them, one and the same thing; and so all prosodies have always understood them and wished them to be understood. They express, indeed, ›short‹; but this word has all kinds of meanings. It serves to represent (the reader is left to guess when) sometimes the half, sometimes the third, sometimes the fourth, sometimes the sixth of ›long‹; while ›long‹ itself, in the books, is left undefined and undescribed. On the other hand, the horizontal accent, it may be said, expresses sufficiently well and unvaryingly the syllables which are meant to be long. It does nothing of the kind. This horizontal accent is placed over the cæsura (wherever, as in the Latin Prosodies, the cæsura is recognized) as well as over the ordinary long syllable, and implies any thing and every thing, just as the crescent. But grant that it does express the ordinary long syllables (leaving the cæsura out of question), have I not given the identical expression by not employing any expression at all? In a word, while the prosodies, with a certain number of accents express precisely nothing whatever, I, with scarcely half the number, have expressed every thing which, in a system of accentuation, demands expression. In glancing at my mode in the lines of Mr.

1 comment