We may as well accent it with the curve of the crescent to the right, and call it a bastard dactyl. A bastard anapæst, whose nature I now need be at no trouble in explaining, will of course occur, now and then, in an anapæstic rhythm.

In order to avoid any chance of that confusion which is apt to be introduced in an essay of this kind by too sudden and radical an alteration of the conventionalities to which the reader has been accustomed, I have thought it right to suggest for the accent marks of the bastard trochee, bastard iambus, etc., etc., certain characters which, in merely varying the direction of the ordinary short accent (), should imply, what is the fact that the feet themselves are not new feet, in any proper sense, but simply modifications of the feet, respectively, from which they derive their names. Thus a bastard iambus is, in its essentiality, – that is to say, in its time, – an iambus. The variation lies only in the distribution of this time. The time, for example, occupied by the one short (or half of long) syllable, in the ordinary iambus, is, in the bastard, spread equally over two syllables, which are accordingly the fourth of long.

But this fact – the fact of the essentiality, or whole time, of the foot being unchanged – is now so fully before the reader that I may venture to propose, finally, an accentuation which shall answer the real purpose – that is to say, what should be the real purpose of all accentuation – the purpose of expressing to the eye the exact relative value of every syllable employed in Verse.

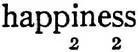

I have already shown that enunciation, or length, is the point from which we start. In other words, we begin with a long syllable. This, then, is our unit; and there will be no need of accenting it at all. An unaccented syllable, in a system of accentuation, is to be regarded always as a long syllable. Thus a spondee would be without accent. In an iambus, the first syllable being ›short,‹ or the half of long, should be accented with a small 2, placed beneath the syllable; the last syllable, being long, should be unaccented: the whole would be thus (control). In a trochee, these accents would be merely conversed, thus ( ). In a dactyl, each of the two final syllables, being the half of long, should, also, be accented with a small 2 beneath the syllable; and, the first syllable left unaccented, the whole would be thus (

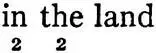

). In a dactyl, each of the two final syllables, being the half of long, should, also, be accented with a small 2 beneath the syllable; and, the first syllable left unaccented, the whole would be thus ( ). In an anapæst we should converse the dactyl, thus (

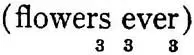

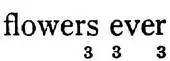

). In an anapæst we should converse the dactyl, thus ( ). In the bastard dactyl, each of the three concluding syllables being the third of long, should be accented with a small 3 beneath the syllable, and the whole foot would stand thus (

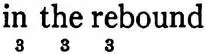

). In the bastard dactyl, each of the three concluding syllables being the third of long, should be accented with a small 3 beneath the syllable, and the whole foot would stand thus ( ). In the bastard anapæst we should converse the bastard dactyl, thus (

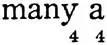

). In the bastard anapæst we should converse the bastard dactyl, thus ( ). In the bastard iambus, each of the two initial syllables, being the fourth of long, should be accented below with a small 4; the whole foot would be thus (

). In the bastard iambus, each of the two initial syllables, being the fourth of long, should be accented below with a small 4; the whole foot would be thus ( ). In the bastard trochee we should converse the bastard iambus, thus (

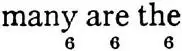

). In the bastard trochee we should converse the bastard iambus, thus ( ). In the quick trochee, each of the three concluding syllables, being the sixth of long, should be accented below with a small 6; the whole foot would be thus (

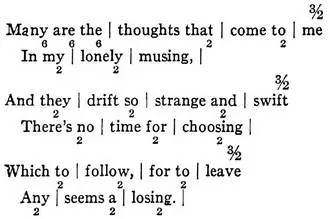

). In the quick trochee, each of the three concluding syllables, being the sixth of long, should be accented below with a small 6; the whole foot would be thus (  ). The quick iambus is not yet created, and most probably never will be, for it will be excessively useless, awkward, and liable to misconception, – as I have already shown that even the quick trochee is, – but, should it appear, we must accent it by conversing the quick trochee. The cæsura, being variable in length, but always longer than ›long,‹ should be accented above, with a number expressing the length or value of the distinctive foot of the rhythm in which it occurs. Thus a cæsura, occurring in a spondaic rhythm, would be accented with a small 2 above the syllable, or, rather, foot. Occurring in a dactylic or anapæstic rhythm, we also accent it with the 2, above the foot. Occurring in an iambic rhythm, however, it must be accented, above, with 11/2, for this is the relative value of the iambus. Occurring in the trochaic rhythm, we give it, of course, the same accentuation. For the complex 11/2, however, it would be advisable to substitute the simpler expression, 3/2, which amounts to the same thing.

). The quick iambus is not yet created, and most probably never will be, for it will be excessively useless, awkward, and liable to misconception, – as I have already shown that even the quick trochee is, – but, should it appear, we must accent it by conversing the quick trochee. The cæsura, being variable in length, but always longer than ›long,‹ should be accented above, with a number expressing the length or value of the distinctive foot of the rhythm in which it occurs. Thus a cæsura, occurring in a spondaic rhythm, would be accented with a small 2 above the syllable, or, rather, foot. Occurring in a dactylic or anapæstic rhythm, we also accent it with the 2, above the foot. Occurring in an iambic rhythm, however, it must be accented, above, with 11/2, for this is the relative value of the iambus. Occurring in the trochaic rhythm, we give it, of course, the same accentuation. For the complex 11/2, however, it would be advisable to substitute the simpler expression, 3/2, which amounts to the same thing.

In this system of accentuation Mr. Cranch's lines, quoted above, would thus be written:

In the ordinary system the accentuation would be thus:

Many are the | thoughts that | come to | me

In my | lonely | musing, |

And they | drift so | strange and | swift |

There's no | time for | choosing |

Which to | follow, | for to | leave

Any | seems a | losing. |

It must be observed here that I do not grant this to be the ›ordinary‹ scansion. On the contrary, I never yet met the man who had the faintest comprehension of the true scanning of these lines, or of such as these. But granting this to be the mode in which our prosodies would divide the feet, they would accentuate the syllables as just above.

Now, let any reasonable person compare the two modes. The first advantage seen in my mode is that of simplicity – of time, labor, and inksaved.

1 comment