Were it demanded of me why the books cut off one vowel before another, I might say: It is, perhaps, because the books think that, since a bad reader is so apt to slide the one vowel into the other at any rate, it is just as well to print them ready-slided. But in the case of the terminating m, which is the most readily pronounced of all consonants (as the infantile mamma will testify), and the most impossible to cheat the ear of by any system of sliding – in the case of the m, I should be driven to reply that, to the best of my belief, the prosodists did the thing, because they had a fancy for doing it, and wished to see how funny it would look after it was done. The thinking reader will perceive that, from the great facility with which em may be enunciated, it is admirably suited to form one of the rapid short syllables in the bastard dactyl ( ); but because the books had no conception of a bastard dactyl, they knocked it on the head at once – by cutting off its tail!

); but because the books had no conception of a bastard dactyl, they knocked it on the head at once – by cutting off its tail!

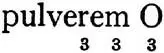

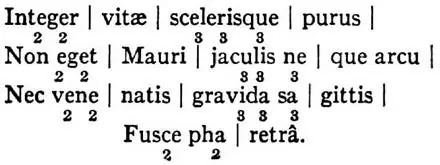

Let me now give a specimen of the true scansion of another Horatian measure – embodying an instance of proper elision.

Here the regular recurrence of the bastard dactyl gives great animation to the rhythm. The e before the a in que arcu, is, almost of sheer necessity, cut off – that is to say, run into the a so as to preserve the spondee. But even this license it would have been better not to take.

Had I space, nothing would afford me greater pleasure than to proceed with the scansion of all the ancient rhythms, and to show how easily, by the help of common-sense, the intended music of each and all can be rendered instantaneously apparent. But I have already overstepped my limits, and must bring this paper to an end.

It will never do, however, to omit all mention of the heroic hexameter.

I began the ›processes‹ by a suggestion of the spondee as the first step toward verse. But the innate monotony of the spondee has caused its disappearance, as the basis of rhythm, from all modern poetry. We may say, indeed, that the French heroic – the most wretchedly monotonous verse in existence – is, to all intents and purposes, spondaic. But it is not designedly spondaic – and if the French were ever to examine it at all, they would no doubt pronounce it iambic. It must be observed that the French language is strangely peculiar in this point – that it is without accentuation, and consequently without verse. The genius of the people, rather than the structure of the tongue, declares that their words are, for the most part, enunciated with a uniform dwelling on each syllable. For example, we say »syllabfication.« A Frenchman would say syl-la-bi-fi-ca-ti-on; dwelling on no one of the syllables with any noticeable particularity. Here again I put an extreme case, in order to be well understood; but the general fact is as I give it – that, comparatively, the French have no accentuation. And there can be nothing worth the name of verse without. Therefore, the French have no verse worth the name – which is the fact, put in sufficiently plain terms. Their iambic rhythm so superabounds in absolute spondees, as to warrant me in calling its basis spondaic; but French is the only modern tongue which has any rhythm with such basis; and even in the French, it is, as I have said, unintentional.

Admitting, however, the validity of my suggestion, that the spondee was the first approach to verse, we should expect to find, first, natural spondees (words each forming just a spondee) most abundant in the most ancient languages; and, secondly, we should expect to find spondees forming the basis of the most ancient rhythms. These expectations are in both cases confirmed.

Of the Greek hexameter, the intentional basis is spondaic. The dactyls are the variation of the theme. It will be observed that there is no absolute certainty about their points of interposition. The penultimate foot, it is true, is usually a dactyl; but not uniformly so; while the ultimate, on which the ear lingers, is always a spondee. Even that the penultimate is usually a dactyl may be clearly referred to the necessity of winding up with the distinctive spondee. In corroboration of this idea, again, we should look to find the penultimate spondee most usual in the most ancient verse; and, accordingly, we find it more frequent in the Greek than in the Latin hexameter.

But besides all this, spondees are not only more prevalent in the heroic hexameter than dactyls, but occur to such an extent as is even unpleasant to modern ears, on account of monotony. What the modern chiefly appreciates and admires in the Greek hexameter, is the melody of the abundant vowel sounds. The Latin hexameters really please very few moderns – although so many pretend to fall into ecstasies about them. In the hexameters quoted, several pages ago, from Silius Italicus, the preponderance of the spondee is strikingly manifest. Besides the natural spondees of the Greek and Latin, numerous artificial ones arise in the verse of these tongues on account of the tendency which inflection has to throw full accentuation on terminal syllables; and the preponderance of the spondee is farther insured by the comparative infrequency of the small prepositions which we have to serve us instead of case, and also the absence of the diminutive auxiliary verbs with which we have to eke out the expression of our primary ones. These are the monosyllables whose abundance serve to stamp the poetic genius of a language as tripping or dactylic.

Now, paying no attention to these facts, Sir Philip Sidney, Professor Longfellow, and innumerable other persons more or less modern, have busied themselves in constructing what they suppose to be »English hexameters on the model of the Greek.« The only difficulty was that (even leaving out of question the melodious masses of vowels) these gentlemen never could get their English hexameters to sound Greek. Did they look Greek? – that should have been the query; and the reply might have led to a solution of the riddle. In placing a copy of ancient hexameters side by side with a copy (in similar type) of such hexameters as Professor Longfellow, or Professor Felton, or the Frogpondian Professors collectively, are in the shameful practice of composing ›on the model of the Greek,‹ it will be seen that the latter (hexameters, not professors) are about one third longer to the eye, on an average, than the former. The more abundant dactyls make the difference.

1 comment