Let us take Mr. Alfred B. Street. I remember these two lines of his:

His sinuous path, by blazes, wound

Among trunks grouped in myriads round.

With the sense of these lines I have nothing to do. When a poet is in a ›fine frenzy,‹ he may as well imagine a large forest as a small one; and ›by blazes‹ is not intended for an oath. My concern is with the rhythm, which is iambic.

Now let us suppose that, a thousand years hence, when the ›American language‹ is dead, a learned prosodist should be deducing, from ›careful observation‹ of our best poets, a system of scansion for our poetry. And let us suppose that this prosodist had so little dependence in the generality and immutability of the laws of Nature, as to assume in the outset, that, because we lived a thousand years before his time, and made use of steam-engines instead of mesmeric balloons, we must therefore have had a very singular fashion of mouthing our vowels, and altogether of hudsonizing our verse. And let us suppose that with these and other fundamental propositions carefully put away in his brain, he should arrive at the line, –

Among | trunks grouped | in my | riads round.

Finding it an obviously iambic rhythm, he would divide it as above; and observing that ›trunks‹ made the first member of an iambus, he would call it short, as Mr. Street intended it to be. Now farther, if instead of admitting the possibility that Mr. Street (who by that time would be called Street simply, just as we say Homer) – that Mr. Street might have been in the habit of writing carelessly, as the poets of the prosodist's own era did, and as all poets will do (on account of being geniuses), – instead of admitting this, suppose the learned scholar should make a ›rule‹ and put it in a book, to the effect that, in the American verse, the vowel u, when found imbedded among nine consonants, was short, what, under such circumstances, would the sensible people of the scholar's day have a right not only to think but to say of that scholar? – why, that he was ›a fool – by blazes!‹

I have put an extreme case, but it strikes at the root of the error. The ›rules‹ are grounded in ›authority‹; and this ›authority‹ – can any one tell us what it means? or can any one suggest any thing that it may not mean? Is it not clear that the ›scholar‹ above referred to, might as readily have deduced from authority a totally false system as a partially true one? To deduce from authority a consistent prosody of the ancient metres would indeed have been within the limits of the barest possibility; and the task has not been accomplished, for the reason that it demands a species of ratiocination altogether out of keeping with the brain of a bookworm. A rigid scrutiny will show that the very few ›rules‹ which have not as many exceptions as examples, are those which have, by accident, their true bases not in authority, but in the omniprevalent laws of syllabification; such, for example, as the rule which declares a vowel before two consonants to be long.

In a word, the gross confusion and antagonism of the scholastic prosody, as well as its marked inapplicability to the reading flow of the rhythms it pretends to illustrate, are attributable, first, to the utter absence of natural principle as a guide in the investigations which have been undertaken by inadequate men; and secondly, to the neglect of the obvious consideration that the ancient poems, which have been the criteria throughout, were the work of men who must have written as loosely, and with as little definitive system, as ourselves.

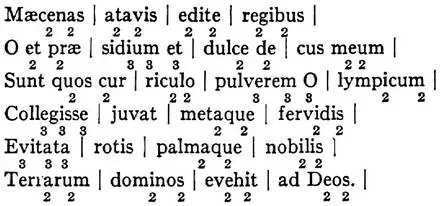

Were Horace alive to-day, he would divide for us his first Ode thus, and ›make great eyes‹ when assured by prosodists that he had no business to make any such division!

Read by this scansion, the flow is preserved; and the more we dwell on the divisions, the more the intended rhythm becomes apparent. Moreover, the feet have all the same time; while, in the scholastic scansion, trochees – admitted trochees – are absurdly employed as equivalents to spondees and dactyls. The books declare, for instance, that Colle, which begins the fourth line, is a trochee, and seem to be gloriously unconscious that to put a trochee in opposition with a longer foot, is to violate the inviolable principle of all music, time.

It will be said, however, by ›some people,‹ that I have no business to make a dactyl out of such obviously long syllables as sunt, quos, cur. Certainly I have no business to do so. I never do so. And Horace should not have done so. But he did. Mr. Bryant and Mr. Longfellow do the same thing every day. And merely because these gentlemen, now and then, forget themselves in this way, it would be hard if some future prosodist should insist upon twisting the »Thanatopsis,« or the »Spanish Student,« into a jumble of trochees, spondees, and dactyls.

It may be said, also, by some other people, that in the word decus, I have succeeded no better than the books, in making the scansional agree with the reading flow; and that decus was not pronounced decus. I reply, that there can be no doubt of the word having been pronounced, in this case, decus. It must be observed, that the Latin inflection, or variation of a word in its terminating syllable, caused the Romans – must have caused them – to pay greater attention to the termination of a word than to its commencement, or than we do to the terminations of our words. The end of the Latin word established that relation of the word with other words which we establish by prepositions or auxiliary verbs. Therefore, it would seem infinitely less odd to them than it does to us, to dwell at any time, for any slight purpose, abnormally, on a terminating syllable. In verse, this license – scarcely a license – would be frequently admitted. These ideas unlock the secret of such lines as the

Litoreis ingens inventa sub ilicibus sus,

and the

Parturiunt montes et nascitur ridiculus mus,

which I quoted, some time ago, while speaking of rhyme.

As regards the prosodial elisions, such as that of rem before O, in pulverem Olympicum, it is really difficult to understand how so dismally silly a notion could have entered the brain even of a pedant.

1 comment