The Storyteller

The Storyteller

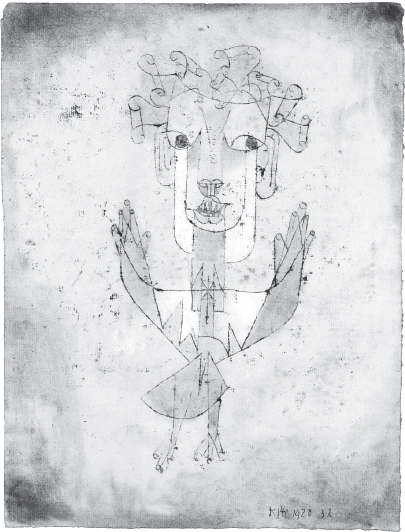

Paul Klee, Angelus Novus, 1920

The Storyteller

Tales Out of Loneliness

Walter Benjamin

With Illustrations

by Paul Klee

Translated and Edited by

Sam Dolbear, Esther Leslie

and Sebastian Truskolaski

First published by Verso 2016

Introduction and Translation © Sam Dolbear, Esther Leslie

and Sebastian Truskolaski 2016

Translation of ‘Nordic Sea’ © Antonia Grousdanidou 2016

In Chapter 16, Albert Welti, Mondnacht, taken from

Albert Welti, Gemälde und Radierungen, Furche Verlag, Berlin, 1917.

In Chapter 34, ‘Wandkalender’ © Akademie der Künste, Berlin,

Walter Benjamin Archiv.

The images by Paul Klee are in the public domain.

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-304-4 (PB)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-307-5 (US EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-306-8 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Benjamin, Walter, 1892–1940, author. | Dolbear, Sam, translator, editor. | Leslie, Esther, 1964– translator, editor. | Truskolaski, Sebastian, translator, editor.

Title: The storyteller : tales out of loneliness / Walter Benjamin ; translated and with an introduction by Sam Dolbear, Esther Leslie and Sebastian Truskolaski.

Description: First [edition]. | Brooklyn, NY : Verso, 2016.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016013569 | ISBN 9781784783044 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Benjamin, Walter, 1892–1940 – Translations into English. | BISAC: FICTION / Short Stories (single author).

Classification: LCC PT2603.E455 A2 2016 | DDC 833/.912 – dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016013569

Typeset in Caslon Pro by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed in the US by Maple Press

Contents

Introduction: Walter Benjamin and the Magnetic Play of Words

by Sam Dolbear, Esther Leslie and Sebastian Truskolaski

PART ONE: DREAMWORLDS

Fantasy

1.Schiller and Goethe: A Layman’s Vision

2.In a Big Old City: Novella Fragment

3.The Hypochondriac in the Landscape

4.The Morning of the Empress

5.The Pan of the Evening

6.The Second Self: A New Year’s Story for Contemplation

Dreams

7.Dreams from Ignaz Jezower’s Das Buch der Träume

8.Too Close

9.Ibizan Dream

10.Self-Portraits of a Dreamer

The Grandson

The Seer

The Lover

The Knower

The Tight-Lipped One

The Chronicler

11.Dream I

12.Dream II

13.Once Again

14.Letter to Toet Blaupot ten Cate

15.A Christmas Song

16.The Moon

Welti’s Moonlit Night

The Water Glass

The Moon

In the Dark

The Dream

17.Diary Notes

18.Review: Albert Béguin, The Romantic Soul and the Dream

PART TWO: TRAVEL

City and Transit

19.Still Story

20.The Aviator

21.The Death of the Father: Novella

22.The Siren

23.Sketched into Mobile Dust: Novella

24.Palais D…y

25.Review: Franz Hessel, Secret Berlin

26.Review: Detective Novels, on Tour

Landscape and Seascape

27.Nordic Sea

Town

Flowers

Furniture

Light

Gulls

Statues

28.Tales Out of Loneliness

The Wall

The Pipe

The Light

29.The Voyage of The Mascot

30.The Cactus Hedge

31.Reviews: Landscape and Travel

PART THREE: PLAY AND PEDAGOGY

32.Review: Collection of Frankfurt Children’s Rhymes

33.Fantasy Sentences

34.Wall Calendar from Die literarische Welt for 1927

35.Riddles

The Stranger’s Reply

Succinct

36.Radio Games

37.Short Stories

Why the Elephant Is Called ‘Elephant’

How the Boat Was Invented and Why It Is Called ‘Boat’

Funny Story from When There Were Not Yet Any People

38.Four Tales

The Warning

The Signature

The Wish

Thanks

39.On the Minute

40.The Lucky Hand: A Conversation about Gambling

41.Colonial Pedagogy: Review of Alois Jalkotzy, The Fairy Tale and the Present

42.Verdant Elements: Review of Tom Seidemann-Freud, Play Primer 2 and 3: Something More on the Play Primer

Notes

Translators’ Note

About the Illustrations: Paul Klee

Throughout his life, Walter Benjamin experimented with a variety of literary forms. Novellas and short stories, fables and parables as well as jokes, riddles and rhymes all sit alongside his well-known critical writings. He also long harboured plans to write crime fiction. There exists an extensive outline for a novel, to be titled La Chasse aux mensonge, detailing ten possible chapters, including such details as an accident in a lift shaft, an umbrella as clue, action in a cardboard-making factory, a man who hides his banknotes inside his books and loses them.1 The sheer variety of Benjamin’s literary texts reflects the often precarious existence that he forged as a freelance author, moving around the continent sporadically taking on assignments for newspapers and journals. The short forms collected in the present volume stand in their own right as works of experimental writing, but they also act as the sounding board for ideas that feed back into Benjamin’s critical work. The Tsarist clerk Shuvalkin and the Hasidic beggar in ‘Four Stories’ (c. 1933–4), for example, resurface in his essay on Franz Kafka (1934).2 Likewise, the Imperial panorama from ‘The Second Self’ (c. 1930–3) recalls the ‘Tour of German Inflation’ described in One Way Street (1928) as well as the essay on ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility’ (1934–5) and the autobiographical vignettes laid out in Berlin Childhood around 1900 (1932–8).3

Charting these continuities is more than a mere exercise in philology. Rather, the purpose of bringing together these texts is to demonstrate how Benjamin formally stages, enacts and performs certain concerns that he develops elsewhere in a more academic register. Consistent across the work is an exploration of such themes as dream and fantasy, travel and estrangement, play and pedagogy. Before commenting directly on the specifics of this topology, however, a discussion of Benjamin’s reflections on storytelling is warranted.

Benjamin treated the theme of storytelling in an array of texts, not least among them ‘The Storyteller’ (1936), an essay on the Russian novelist Nikolai Leskov from which the title of the present volume is drawn.4 In another, a short text titled ‘Experience and Poverty’ (1933), Benjamin lays out the central claim he would later develop in the Leskov essay. Before the onset of the First World War, we are told, experience was passed down through the generations in the form of folklore and fairy tales.5 To illustrate this claim, Benjamin relates a fable about a father who taught his sons the merits of hard work by fooling them into thinking that there was buried treasure in the vineyard by the house. The turning of soil in the vain search for gold results in the discovery of a real treasure: a wonderful crop of fruit. With the war came the severing of ‘the red thread of experience’ which had connected previous generations, as Benjamin puts it in ‘Sketched into Mobile Dust’. The ‘fragile human body’ that emerged from the trenches was mute, unable to narrate the ‘forcefield of destructive torrents and explosions’6 that had engulfed it. Communicability was unsettled. It was as if the good and bountiful soil of the fable had become the sticky and destructive mud of the trenches, which would bear no fruit but only moulder as a graveyard. ‘Where do you hear words from the dying that last and that pass from one generation to the next like a precious ring?’ Benjamin asks.7

By contrast, the journalistic jargon of the newspaper is the highest expression of experiential poverty – a lesson that Benjamin learned from Karl Kraus.8 As Benjamin comments, ‘every morning brings us the news of the globe and yet we are poor in noteworthy stories.’9 But it is precisely for this very reason that seemingly redundant narrative forms become highly charged. Benjamin’s association of experience with folklore and fairy tales cannot be seen as expressing a nostalgic yearning to revive a ruined tradition. Rather, the obsolescence of these forms becomes the condition of their critical function – a point that Benjamin explores in the review ‘Colonial Pedagogy’ with reference to the attempted modernisation of fairy tales. Kafka’s parables elude interpretation because the key to understanding them has been lost, yet the function of this anachronistic opacity is the unfolding of a language of gestures and names: a facet of what has been described as Kafka’s ‘inverse messianism’.10 By the same token, it would appear that the moment for reading Baudelaire’s lyric poetry had passed at the time of its publication, yet it is precisely the untimeliness of its presentation that imbues Baudelaire’s rendition of modern life with the urgency that Benjamin admired. What Benjamin attempts to re-imagine in his engagement with these authors is the communicability of experience in spite of itself. In this regard, it is notable that a common trait of Benjamin’s own fiction is the layering of voices in imitation of an ostensibly antiquated oral tradition: a sea captain tells a passenger a yarn, a friend tells another friend a curious thing that he experienced, a man tells the tale of an acquaintance to another man, who in turn relates the story to us. These stories create layered worlds of citations, enigmas and perspectives. With this, Benjamin extends a long tradition of recording and retelling stories which stretches from Hebel to Hoffmann and beyond.

1 comment