The Tale of Pigling Bland

Beatrix Potter loved the countryside and she spent much of

her otherwise conventional Victorian childhood drawing and studying animals. Her passion for the

natural world lay behind the creation of her famous series of little books. A particular source of

inspiration was the English Lake District where she lived for the last thirty years of her life as a

farmer and land conservationist, working with the National Trust.

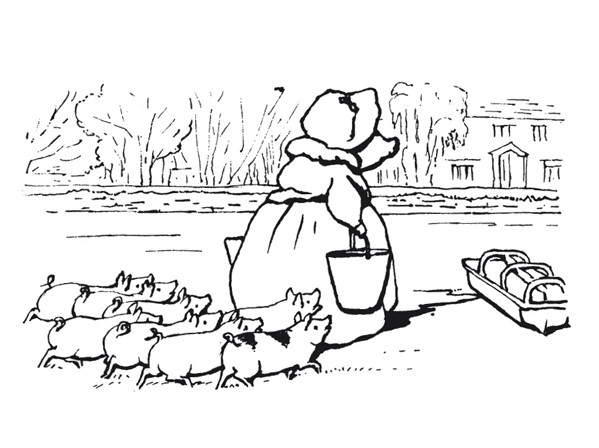

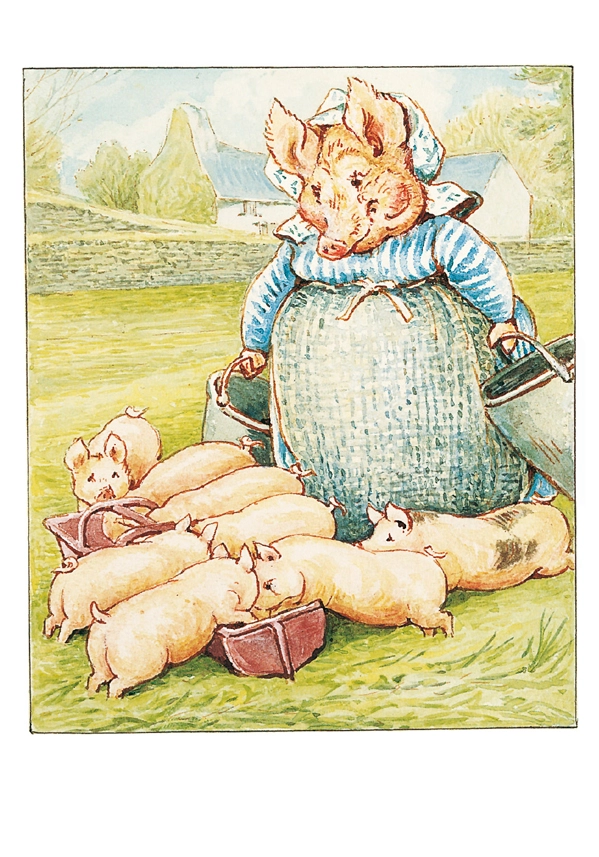

The Tale of Pigling Bland was published in 1913, the year Beatrix Potter married and settled down to farming life for good. But she had already been keeping pigs and she sketched them for this story, using her own farmyard as the setting. One little black pig was a household pet and features as the “perfectly lovely” Pig-wig who runs away with Pigling Bland.

www.peterrabbit.com

for cecily and charlie

a tale of the christmas pig

Once upon a

time there was an old pig called Aunt Pettitoes. She had eight of a family: four little girl

pigs, called Cross-patch, Suck-suck, Yock-yock and Spot; and four little boy pigs, called Alexander, Pigling Bland, Chin-chin and

Stumpy.

Stumpy had had an accident to his tail.

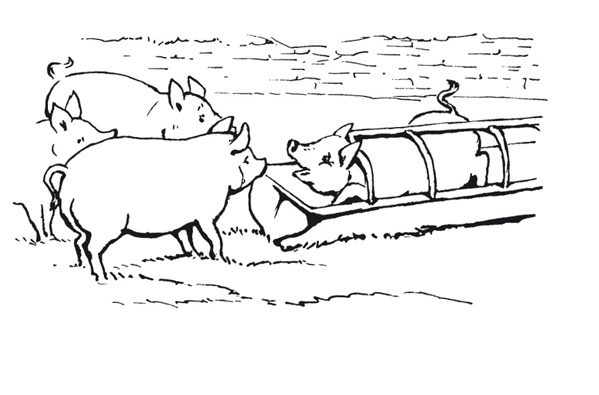

The eight little pigs had very fine appetites — “Yus, yus, yus! they eat and indeed

they do eat!” said Aunt Pettitoes, looking at her family with pride.

Suddenly there were fearful squeals; Alexander had squeezed inside the

hoops of the pig trough and stuck.

Aunt Pettitoes and I dragged him out by the hind legs.

Chin-chin was already in disgrace; it was washing day, and he had eaten a piece of

soap. And presently in a basket of clean clothes, we found another dirty little pig — “Tchut, tut, tut!

whichever is this?” grunted Aunt Pettitoes.

Now all the pig family are pink, or pink with black spots, but this pig child was

smutty black all over; when it had been popped into a tub, it proved to be Yock-yock.

I went into the garden; there I found Cross-patch and Suck-suck rooting up carrots. I

whipped them myself and led them out by the ears. Cross-patch tried to bite me.

“Aunt Pettitoes, Aunt Pettitoes! you are a worthy person, but your family is not well

brought up. Every one of them has been in mischief except Spot and Pigling Bland.”

“Yus, yus!” sighed Aunt Pettitoes. “And they drink bucketfuls of milk; I shall have to

get another cow! Good little Spot shall stay at home to do the housework; but the others must go. Four

little boy pigs and four little girl pigs are too many altogether.

“Yus, yus, yus,” said Aunt Pettitoes, “there will be more to eat without them.”

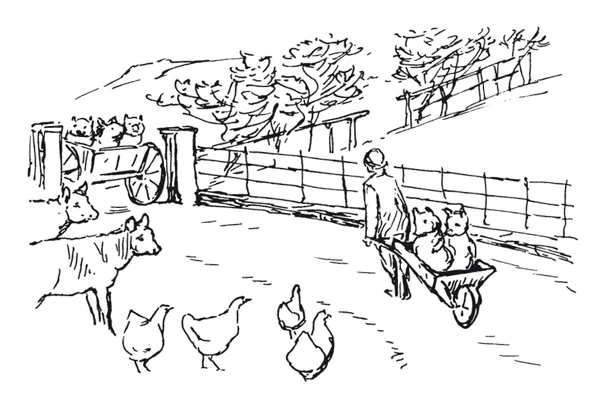

So Chin-chin and Suck-suck went away in a wheelbarrow, and Stumpy, Yock-yock and

Cross-patch rode away in a cart.

And the other two little boy pigs, Pigling Bland and Alexander, went to market.

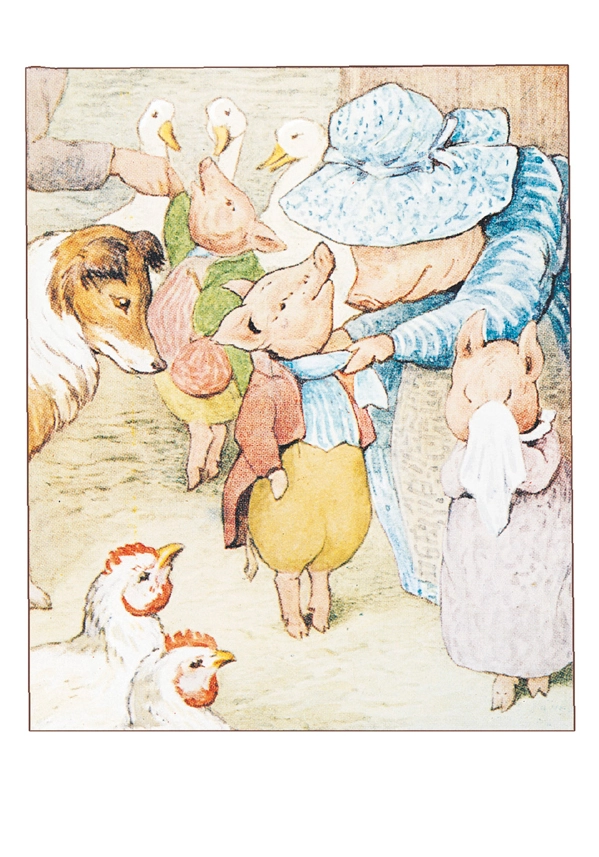

We brushed their coats, we curled their tails and washed their little

faces, and wished them good-bye in the yard.

Aunt Pettitoes wiped her eyes with a large pocket handkerchief, then she wiped Pigling

Bland’s nose and shed tears; then she wiped Alexander’s nose and shed tears; then she passed the

handkerchief to Spot. Aunt Pettitoes sighed and grunted, and addressed those little pigs as follows —

“Now Pigling Bland, son Pigling Bland, you must go to market. Take your brother

Alexander by the hand. Mind your Sunday clothes, and remember to blow your nose” —

(Aunt Pettitoes passed round the handkerchief again) — “beware of

traps, hen roosts, bacon and eggs; always walk upon your hind legs.” Pigling Bland, who was a sedate little

pig, looked solemnly at his mother, a tear trickled down his cheek.

Aunt Pettitoes turned to the other — “Now son Alexander take the hand” — “Wee, wee,

wee!” giggled Alexander — “take the hand of your brother Pigling Bland, you must go to market. Mind —” “Wee,

wee, wee!” interrupted Alexander again. “You put me out,” said Aunt Pettitoes —

“Observe sign-posts and milestones; do not gobble herring bones —” “And remember,” said I

impressively, “if you once cross the county boundary you cannot come back.

Alexander,

you are not attending. Here are two licences permitting two

pigs to go to market in Lancashire. Attend, Alexander. I have had no end of trouble in getting these papers

from the policeman.”

Pigling Bland listened gravely; Alexander was

hopelessly volatile.

I pinned the papers, for safety, inside their waistcoat pockets;

Aunt Pettitoes gave to each a little bundle, and eight conversation peppermints with

appropriate moral sentiments in screws of paper. Then they started.

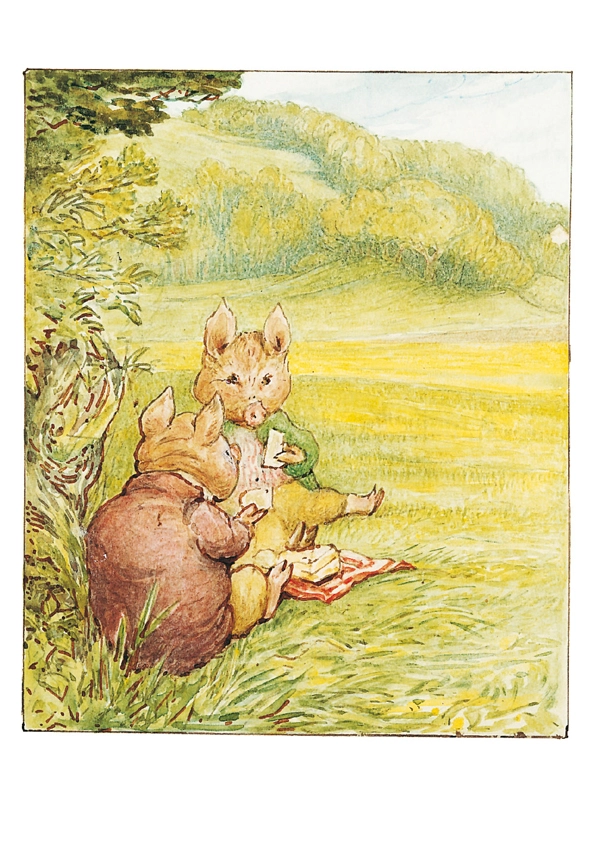

Pigling Bland and Alexander trotted along steadily for a mile; at least Pigling Bland

did. Alexander made the road half as long again by skipping from side to side. He danced about and pinched

his brother, singing —

“This pig went to market, this pig stayed at home,

This pig had a bit of meat —”

“Let’s see what they have given us for dinner,

Pigling?”

Pigling Bland and Alexander sat down and untied their bundles. Alexander gobbled up

his dinner in no time; he had already eaten all his own peppermints — “Give me one of yours, please,

Pigling?”

“But I wish to preserve them for emergencies,” said Pigling

Bland doubtfully. Alexander went into squeals of laughter. Then he pricked Pigling with the pin that had

fastened his pig paper; and when Pigling slapped him he dropped the pin, and tried to take Pigling’s pin,

and the papers got mixed up. Pigling Bland reproved Alexander.

But presently they made it up again, and trotted away together, singing —

“Tom, Tom, the piper’s son,

stole a pig and away he ran!

But all the tune that he could play,

was ‘Over the hills and far away!’”

“What’s that, young sirs? Stole a pig? Where are your licences?” said the policeman.

They had nearly run against him round a corner. Pigling Bland pulled out his paper; Alexander, after

fumbling, handed over something scrumply —

“To 2½oz.

1 comment