Jarry himself seemed to have foreseen this impasse when he wrote on the last page of his manuscript of Faustroll, under the word ‘END’: ‘This book will not be published integrally until the author has acquired sufficient experience to savour all its beauties in full‘, and indeed it was not published until 1911, four years after his death. As Roger Shattuck has written: ‘At twenty-five Jarry suggested he was writing over everyone’s head, including his own; he had to “experience” death in order to catch up with himself.’1

This is not the place to attempt either an examination of the aims of this very complex writer, or an assessment of his impact on the development of twentieth-century French drama and literature,2 but two basic points require to be made: first, that Alfred Jarry was, of course, very much more than the sum of his Ubus, and that the Ubu plays achieve their full dimension within the context of Jarry’s writings on the theatre and, indeed, his whole œuvre, especially Faustroll;3 secondly, that the three Ubu plays are not to be taken as a simple sequence of tragi-comic farces woven around the monstrous central figure of Ubu. There is a basic affinity between Ubu Roi and Ubu Cocu, the first an adaptation by Jarry of an existing text in a continuing schoolboy saga, the second an original contribution to that same saga, and although Jarry later revised both these texts he never departed from the norms set by the small anonymous army of juvenile satirists of the Rennes lycée. Ubu Enchaîné, on the other hand, was the mature work of a twenty-six-year-old author, a detached and consciously contrived exposition of the pataphysical identity of opposites (freedom versus slavery, in this instance) that had already been expressed spontaneously in Ubu Cocu and was implicit in Ubu Roi. The year before writing Ubu Enchaîné Jarry had completed Faustroll, thus codifying his Science of Pataphysics. He was also in a position to draw upon his experience in the professional theatre to impose a certain dramatic discipline on the structure of his new play. The three Ubus do, nevertheless, constitute a real trinity, in which - if one may coin a pious metaphor - Ubu Roi may be considered the Father, Ubu Cocu the Son, and Ubu Enchaîné the Holy Ghost....

Finally, a word about these translations. Jarry’s use of language in the Ubu plays is as unusual as the events he recounts. The schoolboy jargon, the changes in pace and style between staccato repartee and mock-Shakespearean heroic declamation, the puns and obscure jokes all present their particular problems. And then there are the ingenious verbal inventions. The highly suggestive oaths (merdre, cornegidouille, cornephynance), insults (bouffresque, salopin, bourrique) and anatomical references (bouzine, giborgne, oneilles) which abound, particularly in the two earlier plays, derive directly from the accumulated repertory of slang of the Hébertique saga of Rennes, and challenge one to find suitable equivalents in English. How is one to duplicate the majestic, tongue-rolling sonority of the word merdre, given only our bleak, unheroic ‘shit’ to work on? The aerated hiss of ‘pschitt’ provides some labial satisfaction, but can only be considered the best of several inadequate alternatives. On the other hand, Cyril Connolly’s triumphant conversion of cornegidouille into hornstrumpot gave the English language a new expletive when in 1945 he first presented his version of Ubu Cocu in the pages of Horizon.

We have inserted into our joint translation of Ubu Roi those of the songs from the guignol version, Ubu sur la Butte, which could be easily carried over: each such excerpt is clearly indicated in the text, so that for purposes of stage production it will be a simple matter of choice as to whether or not the songs shall be incorporated. We did not complete the Ubu cycle by translating the whole of Ubu sur la Butte, since this two-act guignol reduction of Ubu Roi is mainly of literary interest today, even for those interested in the marionette theatre.

An indispensable companion for the student of Ubu who reads French is Maurice Saillet’s impeccably scholarly Tout Ubu (Le Livre de Poche, Paris, 1962), which contains not only all the Ubu plays, but also a ‘Chronologie du Père Ubu’, the two Almanachs du Père Ubu, and a number of important documents concerning the triumphs and vicissitudes of the Master of Phynances, whom Cyril Connolly was once inspired to dub, prophetically, the ‘Santa Claus of the Atomic Age’.

SIMON WATSON TAYLOR

Ubu Rex

(Ubu Roi)

Drama in five Acts

in prose

Restored in its entirety

as it was performed by

the marionettes of the Theâtre

des Phynances in 1888

Translated by Cyril Connolly and Simon Watson Taylor

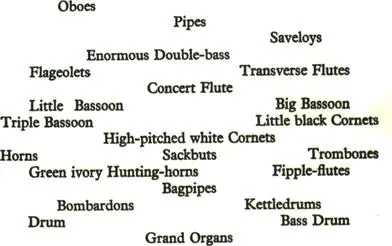

COMPOSITION OF THE ORCHESTRA4

This Book

is dedicated

to

MARCEL SCHWOB

Thereatte Lord Ubu shooke his peare-head, whence he

is by the Englysshe yclept Shakespeare, and you have from

him under thatte name many goodlie tragedies

in his own hande.

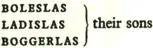

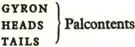

CHARACTERS

PA UBU

MA UBU

CAPTAIN MACNURE

KING WENCESLAS

QUEEN ROSAMUND

GENERAL LASKI

STANISLAS LESZCZYNSKI

JOHN SOBIESKI III

NICOLAS RENSKI

THE TSAR ALEXIS

CONSPIRATORS and SOLDIERS

PEOPLE

MICHAEL FEDOROVITCH

NOBLES

JUDGES

COUNSELLORS

FINANCIERS

LACKEYS OF THE PHYNANCES

PEASANTS

THE ENTIRE RUSSIAN ARMY

THE ENTIRE POLISH ARMY

MA UBU’S GUARDS

A CAPTAIN

THE BEAR

THE PHYNANCE CHARGER

THE DEBRAINING MACHINE

THE CREW

THE SEA-CAPTAIN

The play was originally presented by Lugné-Poe and the Théâtre de l’Œuvre at the Salle du Nouveau Théâtre on December 10th, 1896. The direction was by Lugné-Poe with décor by Paul Sérusier, masks by Alfred Jarry and music by Claude Terrasse.

The cast included Firmin Gémier as Père Ubu and Louise France as Mère Ubu.

Act One

SCENE ONE

PA UBU, MA UBU.

PA UBU. Pschitt!

MA UBU. Ooh what a nasty word. Pa Ubu, you’re a dirty old old man.

PA UBU. Watch out I don’t bash yer nut in, Ma Ubu!

MA UBU. It’s not me you should want to do in, Old Ubu. Oh, no! There’s someone else for the high jump.

PA UBU. By my green candle, I’m not with you.

MA UBU. How come, Old Ubu, you mean you’re content with your lot?

PA UBU. By my green candle, pschitt, Madam. Yes, by God, I’m perfectly satisfied. Who wouldn’t be? Captain of the Dragoons, aide de camp to King Wenceslas, decorated with the order of the Red Eagle of Poland, and ex-King of Aragon. You can’t go higher than that!

MA UBU. So what! After having been King of Aragon, you’re content to ride in reviews at the head of fifty bumpkins armed with billhooks when you could get your loaf measured for the crown of Poland ?

PA UBU. Huh? I don’t understand a word you’re saying, Mother.

MA UBU. How stupid can you get!

PA UBU.

1 comment