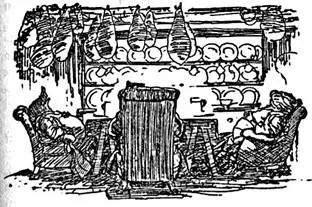

A couple of high-backed settles, facing each other on either side

of the fire, gave further sitting accommodations for the sociably disposed. In

the middle of the room stood a long table of plain boards placed on trestles,

with benches down each side. At one end of it, where an arm-chair stood pushed

back, were spread the remains of the Badger’s plain but ample supper. Rows of

spotless plates winked from the shelves of the dresser at the far end of the

room, and from the rafters overhead hung hams, bundles of dried herbs, nets of

onions, and baskets of eggs. It seemed a place where heroes could fitly feast

after victory, where weary harvesters could line up in scores along the table

and keep their Harvest Home with mirth and song, or where two or three friends

of simple tastes could sit about as they pleased and eat and smoke and talk in

comfort and contentment. The ruddy brick floor smiled up at the smoky ceiling;

the oaken settles, shiny with long wear, exchanged cheerful glances with each

other; plates on the dresser grinned at pots on the shelf, and the merry

firelight flickered and played over everything without distinction.

The kindly

Badger thrust them down on a settle to toast themselves at the fire, and bade

them remove their wet coats and boots. Then he fetched them dressing-gowns and

slippers, and himself bathed the Mole’s shin with warm water and mended the cut

with sticking-plaster till the whole thing was just as good as new, if not

better. In the embracing light and warmth, warm and dry at last, with weary

legs propped up in front of them, and a suggestive clink of plates being

arranged on the table behind, it seemed to the storm-driven animals, now in

safe anchorage, that the cold and trackless Wild Wood just left outside was

miles and miles away, and all that they had suffered in it a half-forgotten

dream.

When at last

they were thoroughly toasted, the Badger summoned them to the table, where he

had been busy laying a repast. They had felt pretty hungry before, but when

they actually saw at last the supper that was spread for them, really it seemed

only a question of what they should attack first where all was so attractive,

and whether the other things would obligingly wait for them till they had time

to give them attention. Conversation was impossible for a long time; and when

it was slowly resumed, it was that regrettable sort of conversation that

results from talking with your mouth full. The Badger did not mind that sort of

thing at all, nor did he take any notice of elbows on the table, or everybody

speaking at once. As he did not go into Society himself, he had got an idea

that these things belonged to the things that didn’t really matter. (We know of

course that he was wrong, and took too narrow a view; because they do matter

very much, though it would take too long to explain why.) He sat in his

arm-chair at the head of the table, and nodded gravely at intervals as the

animals told their story; and he did not seem surprised or shocked at anything,

and he never said, ‘I told you so,’ or, ‘Just what I always said,’ or remarked

that they ought to have done so-and-so, or ought not to have done something

else. The Mole began to feel very friendly towards him.

When supper

was really finished at last, and each animal felt that his skin was now as

tight as was decently safe, and that by this time he didn’t care a hang for

anybody or anything, they gathered round the glowing embers of the great wood

fire, and thought how jolly it was to be sitting up so late, and so

independent, and so full; and after they had chatted for a time about

things in general, the Badger said heartily, ‘Now then! tell us the news from

your part of the world. How’s old Toad going on?’

‘Oh, from bad

to worse,’ said the Rat gravely, while the Mole, cocked up on a settle and

basking in the firelight, his heels higher than his head, tried to look

properly mournful. ‘Another smash-up only last week, and a bad one. You see, he

will insist on driving himself, and he’s hopelessly incapable. If he’d only

employ a decent, steady, well-trained animal, pay him good wages, and leave

everything to him, he’d get on all right. But no; he’s convinced he’s a

heaven-born driver, and nobody can teach him anything; and all the rest

follows.’

‘How many has

he had?’ inquired the Badger gloomily.

‘Smashes, or

machines?’ asked the Rat. ‘Oh, well, after all, it’s the same thing — with

Toad. This is the seventh. As for the others — you know that coach-house of

his? Well, it’s piled up — literally piled up to the roof — with fragments of

motor-cars, none of them bigger than your hat! That accounts for the other six —

so far as they can be accounted for.’

‘He’s been in

hospital three times,’ put in the Mole; ‘and as for the fines he’s had to pay,

it’s simply awful to think of.’

‘Yes, and

that’s part of the trouble,’ continued the Rat. ‘Toad’s rich, we all know; but

he’s not a millionaire. And he’s a hopelessly bad driver, and quite regardless

of law and order. Killed or ruined — it’s got to be one of the two things,

sooner or later. Badger! we’re his friends — oughtn’t we to do something?’

The Badger

went through a bit of hard thinking. ‘Now look here!’ he said at last, rather

severely; ‘of course you know I can’t do anything now?’

His two

friends assented, quite understanding his point. No animal, according to the

rules of animal-etiquette, is ever expected to do anything strenuous, or

heroic, or even moderately active during the off-season of winter. All are

sleepy — some actually asleep. All are weather-bound, more or less; and all are

resting from arduous days and nights, during which every muscle in them has

been severely tested, and every energy kept at full stretch.

‘Very well

then!’ continued the Badger.

1 comment