“Live for others!” That’s my motto

in life.’

During

luncheon — which was excellent, of course, as everything at Toad Hall always

was — the Toad simply let himself go. Disregarding the Rat, he proceeded to

play upon the inexperienced Mole as on a harp. Naturally a voluble animal, and

always mastered by his imagination, he painted the prospects of the trip and

the joys of the open life and the roadside in such glowing colours that the

Mole could hardly sit in his chair for excitement. Somehow, it soon seemed

taken for granted by all three of them that the trip was a settled thing; and

the Rat, though still unconvinced in his mind, allowed his good-nature to

over-ride his personal objections. He could not bear to disappoint his two

friends, who were already deep in schemes and anticipations, planning out each

day’s separate occupation for several weeks ahead.

When they were

quite ready, the now triumphant Toad led his companions to the paddock and set

them to capture the old grey horse, who, without having been consulted, and to

his own extreme annoyance, had been told off by Toad for the dustiest job in

this dusty expedition. He frankly preferred the paddock, and took a deal of

catching. Meantime Toad packed the lockers still tighter with necessaries, and

hung nosebags, nets of onions, bundles of hay, and baskets from the bottom of

the cart. At last the horse was caught and harnessed, and they set off, all

talking at once, each animal either trudging by the side of the cart or sitting

on the shaft, as the humour took him. It was a golden afternoon. The smell of

the dust they kicked up was rich and satisfying; out of thick orchards on

either side the road, birds called and whistled to them cheerily; good-natured

wayfarers, passing them, gave them ‘Good-day,’ or stopped to say nice things

about their beautiful cart; and rabbits, sitting at their front doors in the

hedgerows, held up their fore-paws, and said, ‘O my! O my! O my!’

Late in the

evening, tired and happy and miles from home, they drew up on a remote common

far from habitations, turned the horse loose to graze, and ate their simple

supper sitting on the grass by the side of the cart. Toad talked big about all

he was going to do in the days to come, while stars grew fuller and larger all

around them, and a yellow moon, appearing suddenly and silently from nowhere in

particular, came to keep them company and listen to their talk. At last they

turned in to their little bunks in the cart; and Toad, kicking out his legs, sleepily

said, ‘Well, good night, you fellows! This is the real life for a gentleman!

Talk about your old river!’

‘I don’t

talk about my river,’ replied the patient Rat. ‘You know I don’t, Toad.

But I think about it,’ he added pathetically, in a lower tone: ‘I think

about it — all the time!’

The Mole

reached out from under his blanket, felt for the Rat’s paw in the darkness, and

gave it a squeeze. ‘I’ll do whatever you like, Ratty,’ he whispered. ‘Shall we

run away to-morrow morning, quite early — very early — and go back to

our dear old hole on the river?’

‘No, no, we’ll

see it out,’ whispered back the Rat. ‘Thanks awfully, but I ought to stick by

Toad till this trip is ended. It wouldn’t be safe for him to be left to

himself. It won’t take very long. His fads never do. Good night!’

The end was

indeed nearer than even the Rat suspected.

After so much

open air and excitement the Toad slept very soundly, and no amount of shaking

could rouse him out of bed next morning. So the Mole and Rat turned to, quietly

and manfully, and while the Rat saw to the horse, and lit a fire, and cleaned

last night’s cups and platters, and got things ready for breakfast, the Mole

trudged off to the nearest village, a long way off, for milk and eggs and

various necessaries the Toad had, of course, forgotten to provide. The hard

work had all been done, and the two animals were resting, thoroughly exhausted,

by the time Toad appeared on the scene, fresh and gay, remarking what a

pleasant easy life it was they were all leading now, after the cares and

worries and fatigues of housekeeping at home.

They had a

pleasant ramble that day over grassy downs and along narrow by-lanes, and

camped as before, on a common, only this time the two guests took care that

Toad should do his fair share of work. In consequence, when the time came for

starting next morning, Toad was by no means so rapturous about the simplicity

of the primitive life, and indeed attempted to resume his place in his bunk,

whence he was hauled by force. Their way lay, as before, across country by

narrow lanes, and it was not till the afternoon that they came out on the

high-road, their first high-road; and there disaster, fleet and unforeseen,

sprang out on them — disaster momentous indeed to their expedition, but simply

overwhelming in its effect on the after-career of Toad.

They were

strolling along the high-road easily, the Mole by the horse’s head, talking to

him, since the horse had complained that he was being frightfully left out of

it, and nobody considered him in the least; the Toad and the Water Rat walking

behind the cart talking together — at least Toad was talking, and Rat was

saying at intervals, ‘Yes, precisely; and what did you say to him?’

— and thinking all the time of something very different, when far behind them

they heard a faint warning hum; like the drone of a distant bee. Glancing back,

they saw a small cloud of dust, with a dark centre of energy, advancing on them

at incredible speed, while from out the dust a faint ‘Poop-poop!’ wailed like

an uneasy animal in pain. Hardly regarding it, they turned to resume their

conversation, when in an instant (as it seemed) the peaceful scene was changed,

and with a blast of wind and a whirl of sound that made them jump for the

nearest ditch, It was on them! The ‘Poop-poop’ rang with a brazen shout in

their ears, they had a moment’s glimpse of an interior of glittering

plate-glass and rich morocco, and the magnificent motor-car, immense,

breath-snatching, passionate, with its pilot tense and hugging his wheel,

possessed all earth and air for the fraction of a second, flung an enveloping

cloud of dust that blinded and enwrapped them utterly, and then dwindled to a

speck in the far distance, changed back into a droning bee once more.

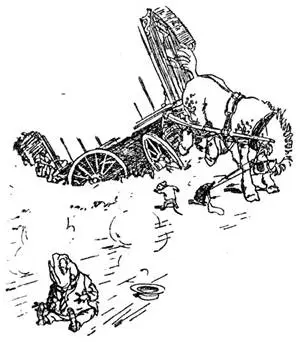

The old grey

horse, dreaming, as he plodded along, of his quiet paddock, in a new raw

situation such as this simply abandoned himself to his natural emotions.

Rearing, plunging, backing steadily, in spite of all the Mole’s efforts at his

head, and all the Mole’s lively language directed at his better feelings, he

drove the cart backwards towards the deep ditch at the side of the road. It wavered

an instant — then there was a heartrending crash — and the canary-coloured

cart, their pride and their joy, lay on its side in the ditch, an irredeemable

wreck.

The Rat danced

up and down in the road, simply transported with passion. ‘You villains!’ he

shouted, shaking both fists, ‘You scoundrels, you highwaymen, you — you —

roadhogs! — I’ll have the law of you! I’ll report you! I’ll take you through all

the Courts!’ His home-sickness had quite slipped away from him, and for the

moment he was the skipper of the canary-coloured vessel driven on a shoal by

the reckless jockeying of rival mariners, and he was trying to recollect all

the fine and biting things he used to say to masters of steam-launches when

their wash, as they drove too near the bank, used to flood his parlour-carpet

at home.

Toad sat

straight down in the middle of the dusty road, his legs stretched out before

him, and stared fixedly in the direction of the disappearing motor-car. He

breathed short, his face wore a placid satisfied expression, and at intervals

he faintly murmured ‘Poop-poop!’

The Mole was

busy trying to quiet the horse, which he succeeded in doing after a time. Then

he went to look at the cart, on its side in the ditch.

1 comment