He seemed at first reluctant to undertake the task, and of course the Air Ministry did not like having their Supply Branch separated from them. There were other resistances to his appointment. I felt sure, however, that our life depended upon the flow of new aircraft; I needed his vital and vibrant energy, and I persisted in my view.

* * * * *

In deference to prevailing opinions expressed in Parliament and the press it was necessary that the War Cabinet should be small. I therefore began by having only five members, of whom one only, the Foreign Secretary, had a Department. These were naturally the leading party politicians of the day. For the convenient conduct of business, it was necessary that the Chancellor of the Exchequer and the leader of the Liberal Party should usually be present, and as time passed the number of “constant attenders” grew. But all the responsibility was laid upon the five War Cabinet Ministers. They were the only ones who had the right to have their heads cut off on Tower Hill if we did not win. The rest could suffer for departmental shortcomings, but not on account of the policy of the State. Apart from the War Cabinet, no one could say “I cannot take the responsibility for this or that.” The burden of policy was borne at a higher level. This saved many people a lot of worry in the days which were immediately to fall upon us.

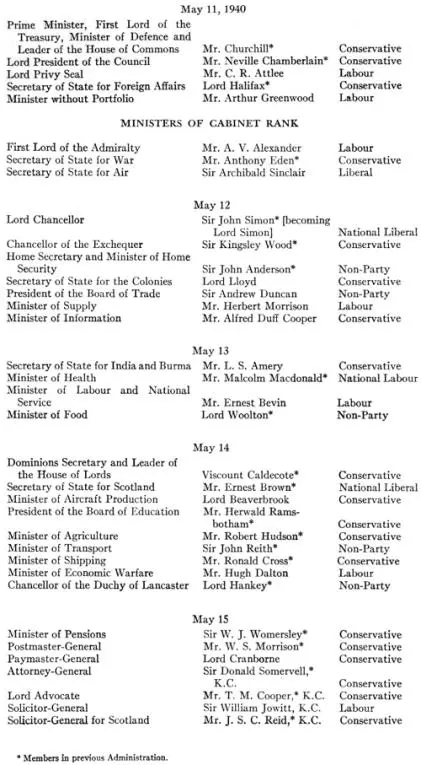

Here are the stages by which the National Coalition Government was built up day by day in the course of the great battle.

THE WAR CABINET

In my long political experience I had held most of the great offices of State, but I readily admit that the post which had now fallen to me was the one I liked the best. Power, for the sake of lording it over fellow-creatures or adding to personal pomp, is rightly judged base. But power in a national crisis, when a man believes he knows what orders should be given, is a blessing. In any sphere of action there can be no comparison between the positions of number one and number two, three, or four. The duties and the problems of all persons other than number one are quite different and in many ways more difficult. It is always a misfortune when number two or three has to initiate a dominant plan or policy. He has to consider not only the merits of the policy, but the mind of his chief; not only what to advise, but what it is proper for him in his station to advise; not only what to do, but how to get it agreed, and how to get it done. Moreover, number two or three will have to reckon with numbers four, five, and six, or maybe some bright outsider, number twenty. Ambition, not so much for vulgar ends, but for fame, glints in every mind. There are always several points of view which may be right, and many which are plausible. I was ruined for the time being in 1915 over the Dardanelles, and a supreme enterprise was cast away, through my trying to carry out a major and cardinal operation of war from a subordinate position. Men are ill-advised to try such ventures. This lesson had sunk into my nature.

At the top there are great simplifications. An accepted leader has only to be sure of what it is best to do, or at least to have made up his mind about it. The loyalties which centre upon number one are enormous. If he trips, he must be sustained. If he makes mistakes, they must be covered. If he sleeps, he must not be wantonly disturbed. If he is no good, he must be pole-axed. But this last extreme process cannot be carried out every day; and certainly not in the days just after he has been chosen.

* * * * *

The fundamental changes in the machinery of war direction were more real than apparent.

1 comment