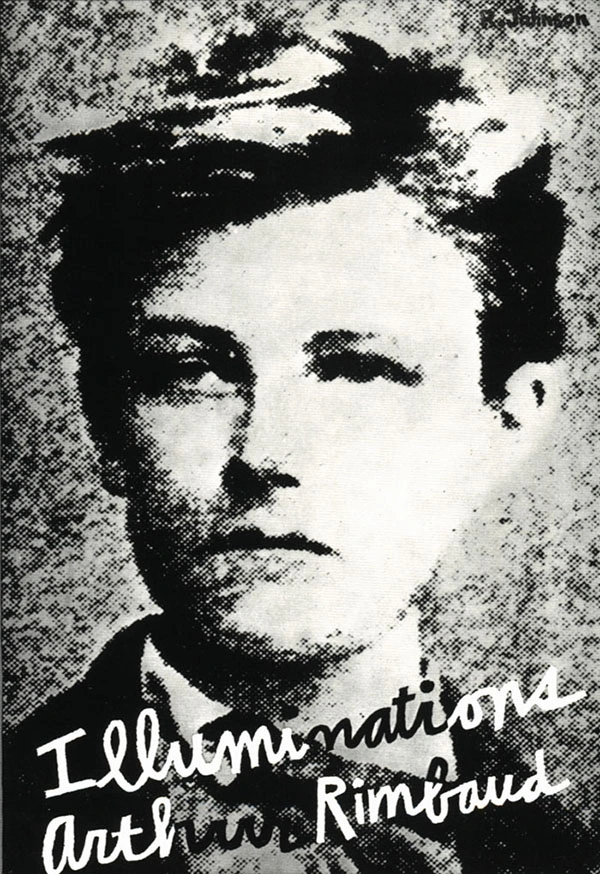

Illuminations

ILLUMINATIONS

RIMBAUD

ILLUMINATIONS

and

Other Prose Poems

TRANSLATED BY

LOUISE VARÈSE

REVISED EDITION

A NEW DIRECTIONS EBOOK

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

BY WAY OF A PREFACE (Les

Lettres du Voyant)

ILLUMINATIONS

(Illuminations)

AFTER THE DELUGE (Après le

Déluge)

CHILDHOOD (Enfance)

TALE (Conte)

SIDE SHOW (Parade)

ANTIQUE (Antique)

BEAUTEOUS BEING (Being

Beauteous)

LIVES (Vies)

DEPARTURE (Départ)

ROYALTY (Royauté)

TO A REASON (A une

Raison)

MORNING OF DRUNKENNESS (Matinée

d’lvresse)

PHRASES (Phrases)

WORKING PEOPLE (Ouvriers)

THE BRIDGES (Les Ponts)

CITY (Ville)

RUTS (Ornières)

CITIES (Villes)

VAGABONDS (Vagabonds)

CITIES (Villes)

VIGILS (Veillées)

MYSTIC (Mystique)

DAWN (Aube)

FLOWERS (Fleurs)

COMMON NOCTURNE (Nocturne

Vulgaire)

MARINE (Marine)

WINTER FÊTE (Fête

d’Hiver)

ANGUISH (Angoisse)

METROPOLITAN

(Métropolitain)

BARBARIAN (Barbare)

PROMONTORY (Promontoire)

SCENES (Scènes)

HISTORIC EVENING (Soir

Historique)

MOTION (Mouvement)

BOTTOM (Bottom)

H (H)

DEVOTIONS (Dévotion)

DEMOCRACY (Démocratie)

FAIRY (Fairy)

WAR (Guerre)

GENIE (Génie)

YOUTH (Jeunesse)

SALE (Solde)

OTHER PROSE

POEMS

THE DESERTS OF LOVE (Les Déserts de

l’Amour)

THREE GOSPEL MORALITIES (Trois

Méditations Johanniques)

Notes on Some Corrections and

Revisions

A Rimbaud Chronology

INTRODUCTION

BY LOUISE VARÈSE

ILLUMINATIONS

Since the original New Directions publication of

Illuminations (1946), Rimbaud’s manuscripts have been made available

to some French scholars. Two editions have resulted: Henri de Bouillane de

Lacoste’s Illuminations, Edition Critique (Mercure de France, 1949), and

the Pléiade edition, Rimbaud, Œuvres Complètes (Gallimard,

1946), edited by Rolland de Renéville and Jules Mouquet. Now, with the errors of

former editors corrected, we probably have the poems as Rimbaud left them. In revising

my translation I have consulted both the Pléiade and de Lacoste’s

Edition Critique.

The French text I originally used was that of Paterne Berrichon’s 1912 edition of

Œuvres de Rimbaud, in the 1924 printing (Mercure de France), which

was the standard edition for many years. It contains Paul Claudel’s famous

preface, a pious amen to Isabelle Rimbaud’s sanctification of her brother, in

which he calls Rimbaud “a mystic in the savage state.”

The history of the peregrinations of the manuscript of Illuminations, like

everything to do with Rimbaud, is still a matter of dispute among the specialists. Most

of our information comes from Verlaine, who certainly knew more about Rimbaud than any

one else, but whose native deviousness and inability to say anything simply and clearly

make most of his statements subject to interpretation, and the interpretations have

confused the confusion. It seems at least more than probable that in 1875 Rimbaud gave

the manuscript to Verlaine when, after being released from prison, he pursued his former

“companion in hell” to Stuttgart in a futile attempt to renew their

friendship. It is also more likely than not that it was the same manuscript which

Verlaine (mentioning simply “prose poems”) says, in a letter written

shortly after his visit to Stuttgart, that he had immediately sent, at Rimbaud’s

request, to Germain Nouveau in Brussels. How the poems later came into the possession of

Charles de Sivry, Verlaine’s brother-in-law, is still a mystery. After that they

passed through several hands before being published for the first time in five issues of

a Symbolist periodical, La Vogue, in 1886. That same year La Vogue

brought them out in book form. Then Félix Fénéon, who had been

entrusted with preparing the manuscript for publication, returned it to the publisher,

Gustave Kahn. Instead of sending it to Verlaine, who had long been claiming it, Kahn,

after holding it for some time, at last, unfortunately, let it be dispersed, giving or

selling it here and there. Today, with the exception of the autographs of

Democracie, Devotion and Genie, which have been lost or are still

in hiding, the manuscript is divided among several collectors, the bulk of it

(thirty-four poems) being in the Lucien-Graux collection.

As for the original order of the poems, Bouillane de Lacoste, after exchanging many

letters with Félix Fénéon on the subject, came to the conclusion

that, except where two or three poems are written on the same page, there is no way of

determining the order assigned them by Rimbaud. After half a century it is hardly

surprising that there were lacunae in Fénéon’s memories. He

describes the manuscript as “a sheaf of loose, unnumbered sheets” of ruled

paper, like the paper in schoolboy copybooks (now they are handsomely bound in red

morocco!). He cannot remember if the present pagination is his or not, or whether the

poems in the periodical La Vogue were brought out in the order they were in

when he received the manuscript. But since the manuscript had been handled by many

persons after Rimbaud parted with it in Stuttgart, even that order may not have been

his. For this edition I have adopted the same order as the Pléiade which, for the

first thirty-seven poems, is the same as that in which they first appeared. These are

followed by five which were not discovered until later and were published by Vanier in

1895. Considering the unrelated nature of the poems (do I hear voices raised in

protest?) the whole question seems rather academic and unimportant. This order is at

least preferable to that of Berrichon which I followed before. Berrichon, not having

seen the manuscript, could not respect even the sequence of the poems written on the

same page, which the present order preserves.

It is again through Verlaine and Verlaine alone that we know Rimbaud’s title. The

word “Illuminations” does appear once in the manuscript at the end of

Promontoire between parentheses, but not, the experts say, in

Rimbaud’s handwriting. Although the work has always been called Les

Illuminations by successive editors and critics (with the exception of de

Lacoste), the first time Verlaine mentions it, in a letter to his brother-in-law,

Charles de Sivry, in 1878, he calls it simply Illuminations: “Have

re-read Illuminations (painted plates)….” Writing at a later

period he explains that “the word is English and means gravures

coloriées, colored plates.” That, he says, was the subtitle

Rimbaud intended to give his work. To many exegetes it is a kind of sacrilege to suggest

that the title could mean anything so simple as colored prints. Verlaine did not

understand Rimbaud anyway, they say, and they could even point out that Rimbaud said so

himself. In Une Saison en Enfer (Delire I ), he has the Foolish Virgin

(Verlaine) lament: “I was sure of never entering his world.… Sometimes

chagrined and sad I said to him, I understand you. He would shrug his shoulders.”

On the other hand gravures coloriées inevitably recalls Rimbaud’s

enluminures coloriées, the brightly colored cheap popular prints or

“images d’Epinal” of the period, which he lists in

Alchemie du Verbe among the things that delighted him at the time when he

“held in derision the celebrities of modern painting and poetry.” But

“colored plates,” or prints, would be a most misleading subtitle if, as

some critics suggest, Illuminations means enluminures in the sense of

medieval illuminated parchments, which were hand colored and not gravures. Or

if, as the saint-seer-angel-God cults must perforce believe, Rim-baud intended

Illuminations to be taken in the figurative sense, philosophic or

religious—the sudden enlightenment of the mind or spirit, either by abstract

wisdom or God (the same in both French and English)—he did not tell the Foolish

Virgin.

1 comment