From hand to hand it passed;

The muddy bottom disappeared and soon enough

The cavity was filled, for they worked fast.

Then to the walls they levelled out the rough.

The duke, the Count and Oliver now call

Upon the infantry to scale the wall.

18

The Nubians, impatient of delay,

Lured by the hope of booty, disregard

The heavy price which they might have to pay.

In ‘tortoises’ and ‘cats’ themselves they guard.

Equipped with battering-rams (a vast array),

They move towards the citadel, prepared

To break down towers and gates, to breach the walls –

And find the Moors on watch for what befalls.

19

Fire, metal missiles, roofs and merlons pour

In molten rain and like a tempest burst,

Shattering planks and beams assembled for

The catapults and siege-machines; at first

During the darkest of the hours before

The dawn, the baptized heads came off the worst;

But when the sun had left his rich abode,

Fortune turned hostile to the pagan brood.

20

Orlando gives the order to increase

The strength of the attack by sea and land.

The fleet which a mile off at anchor is

Now enters port and opens fire as planned.

Arrows and sling-stones fly without surcease,

And engines operate on every hand.

Ladders and spears meanwhile assembled are

With the full arsenal of naval war.

21

Orlando, Oliver and Brandimart

And he who flew so boldly through the skies

A fierce attack now launch upon that part

Which from the sea the farthest inland lies.

Each paladin commands a quarter part

Of the remaining troops, and with them hies

To beat down walls or gates; no matter where

They go, their valour shines beyond compare,

22

Which can be better seen than if they fought

Pell-mell; all those deserving of esteem,

All those by whom the bravest deeds are wrought,

Are obvious to many watching them.

On wheeled contraptions wooden towers are brought,

And elephants, trained for such stratagem,

Bring others on their backs, which reach so high,

The battlements far down below them lie.

23

The valiant Brandimarte came; he put

A ladder to the wall and up he went,

Encouraging his men to follow suit;

And many did so, bold and confident,

Thronging the rungs with many an eager foot;

And no one heeded if the ladder bent

Beneath the weight; the foe his sole concern,

Their leader clambers up and does not turn.

24

No skill in climbing Brandimarte lacks.

Now on the ramparts, brandishing his blade,

He slashes, slices, pierces, thrusts and hacks,

And amply shows the stuff of which he’s made;

But all at once the burdened ladder cracks

(Too much the unforeseeing climbers weighed)

And, save for Brandimarte, one and all

Head over heels into the gulley fall.

25

But Brandimarte’s courage does not fail.

He has no thought of making a retreat.

An easy target now, he does not quail,

Nor listen to the voices which entreat

Him to return (and how could they prevail?);

And though the ramparts measure ninety feet

From top to bottom (as I have heard tell),

He jumps below into the citadel.

26

As if he landed upon down or straw,

He hit the ground without the slightest jolt.

He cut, he ripped, he slashed all those he saw,

Just as one slashes, rips and cuts a bolt

Of cloth; the others hastily withdraw

And if he makes to follow them, they bolt;

While those outside who saw him leap within

Think nothing now can save the paladin.

27

Through all the camp a buzz of rumour flies.

From voice to voice the murmur swells and grows.

Rumour, once vague, repeated, gathers size,

Increasing danger everywhere it goes.

To Oliver, to Otto’s son, it hies,

And to Orlando, eager to disclose

The message of ill-fortune which it brings,

No rest affording to its rapid wings.

28

These warriors (Orlando most of all)

Love and hold Brandimarte in esteem.

They know that they must leave no interval

In rescuing a comrade such as him.

So, placing ladders up against the wall,

They climb and show themselves; so fierce and grim,

Of those three heads so angry is the glare,

The enemy, to see them, quake with fear.

29

As when at sea the stormy waters lash

A ship which too adventurous has been:

Against the prow, against the poop they dash,

Seething with fury, seeking a way in;

The pilot, pale, can only groan and gnash,

His wits adrift, his courage turned to spleen;

One wave engulfs his vessel with a roar

And where that enters, all the others pour;

30

So, when these three had stormed the bastion,

The breach they opened was so large and wide,

The others could then safely follow on.

A thousand ladders were affixed outside.

Meanwhile, the battering-rams now more than one

Way in, with a loud, rumbling crash, provide.

Thus many entrances at once are made

Through which to bring bold Brandimarte aid.

31

With the same rage as when the stately king

Of rivers banks and margins overtops

And, on the fields of Ocnus trespassing,

Rich plough-lands sweeps along and fruitful crops,

A flock complete with winter quartering,

The dogs, the shepherd, while in elm-tree tops

Fishes are seen to dart where formerly

Birds flying to and fro we used to see,

32

With that same rage the impetuous soldiery

Rushed through the spaces in the broken wall

With blazing torches, gleaming weaponry,

To kill those ill-led pagans once for all.

Violent hands were laid on property

And persons, bringing to a rapid fall

The city, rich with many spoils of war,

Which once was queen of all of Africa.

33

The dead lie everywhere; from countless wounds

A swamp has formed which more repellent is,

And darker, than the quagmire which surrounds

The Fury-ridden battlements of Dis.

From house to house a trail of fire compounds

Destruction, burning mosques and palaces.

From houses plundered of possessions, cries

And shrieks and thuds of beaten breasts arise.

34

Laden with booty, victors are seen leaving

Ill-omened doorways, silver figurines

Of household gods or vases in their thieving

Hands, or rich garments; pitiable scenes

Occur as children are dragged forth or grieving

Mothers raped; for here no mercy intervenes.

That day a thousand unjust deeds are done.

The Count, the duke, are powerless to stop one.

35

King Bucifar of Algaziers was slain

By one of valiant Oliver’s shrewd blows.

Seeing all hope and courage were in vain,

Release by his own hand Branzardo chose.

Astolfo struck three times : in triple pain

The life of Folvo flickered to its close.

King Agramante left these three behind

To guard Biserta and its treasures mind.

36

Meanwhile the king, who with Sobrino fled,

Had seen the conflagration on the shore.

Mourning Biserta, bitter tears he shed,

Then, drawing closer, he wept even more

To learn the truth: his city, people said,

Would never now be what it was before.

He even contemplated suicide

But, for Sobrino, put this thought aside.

37

Sobrino said, ‘What happier victory,

My liege, than the report of your demise

Could be imagined by your enemy,

Who would, unchallenged, then enjoy the prize

Of Africa in all security?

But your existence all such hope denies.

He knows he cannot long hold Africa

Unless departed from this life you are.

38

‘Your subjects by your death would be deprived

Of hope – the only asset left to them.

I trust that if you live, those who survived

You may yet from imprisonment redeem,

From misery withdrawn, their strength revived.

I know that if you die, you will condemn

Our land to servitude; live then to spare

Us that, if for your life you cease to care.

39

‘Your neighbour, Egypt’s Sultan, will not fail

To send you troops’ and money; he’ll not let

King Pepin’s son in Africa prevail.

And Norandino is your kinsman yet:

He’ll drive your enemies beyond the pale

And on your throne again you will be set.

Armenians, Turks and Persians, Arabs, Medes,

If you but ask them, will supply your needs.’

40

With similar advice the shrewd old man

Tries to restore his liege’s confidence

That all may not be lost, that soon he can

Recover Africa; and yet events

Such hope (it may be) from his bosom ban.

He knows how bitterly a king repents

Who, having lost his realm, must turn for aid

To foreigners; this error many made.

41

Good witnesses to that were Hannibal,

Jugurtha and many a king of old

And Ludovico il Moro, to the Gaul

(Another Ludovic!) by allies sold.

Your brother, Duke Alfonso, learnt from all

Such cases; he, my lord, is known to hold

That anyone who trusts in others more

Than in himself is mad beyond all cure.

42

Thus, when the Pope, enraged, made war on him,

Although the duke’s resources were but weak,

And slight were the defences he could scheme,

And though his would-be champion, to check

Invasion of his land (as it would seem)

Had fled from Italy, he would not seek

For aid, and for no promise, for no threat,

Would he his realm to alien hands commit.

43

Meanwhile King Agramante eastwards sailed,

Making far out into the open sea,

When from the land an angry storm assailed

The ship, lashing her side with savagery.

The pilot, sitting at the helm, bewailed

(As he looked up) the signs which he could see:

‘So violent a tempest looms,’ he said,

‘I fear the vessel now will make no head.

44

‘If you will follow my advice, my lords,

Until the fury of the storm is spent,

There is an island we should run towards,

Close by, to port.’ The king gave his consent,

And to the shelter which the beach affords

To many a hard-pressed seaman, they now went.

It lies between the shore of Africa

And where the furnaces of Vulcan are.

45

The little isle, of habitation bare,

With humble tamarisk and myrtle clad,

Offered the stag, the roebuck and the hare

A solitude remote, secure and glad,

Unknown except to fishermen; and there

They hung their nets on branches which they had

For this same purpose of their foliage stripped,

While fishes in the tranquil waters slept.

46

The fugitives discovered soon that Fate

Had forced another vessel to the isle,

Bearing Gradasso, whom we saw of late

At Arles (Baiardo he’d procured meanwhile).

Once on dry land, the warrior-kings with great

And mutual respect in regal style

Embraced, for they were friends, and comrades too:

Shared combat beneath Paris’ walls they knew.

47

With deep dismay the Sericanian heard

The Moor’s account of the catastrophe,

And to its depths his loyal soul was stirred.

He promised his support, in chivalry;

But to seek aid from Egypt, he averred,

Would be too dangerous. ‘The memory

Of Pompey should suffice’, he said, ‘to warn

All fugitives who to that quarter turn.

48

‘But since you say Astolfo, with the aid

Of Ethiops, the folk of Prester John,

This onslaught against Africa has made,

Burning your capital, and that the son

Of Milo, who till recently was mad,

Is with him too, I have now hit upon

The very plan, I think, whereby you may

Recoup your losses and your grief allay.

49

‘I will engage Orlando, for your sake,

In single combat; you need have no fear,

For no defence against me could he make

If solid iron or bronze his body were.

When he is dead, the Christian force will quake

Like lambs before a hungry wolf, I swear.

I know too how to drive the Nubians out.

I’ll do that in an instant – have no doubt.

50

‘I will command the other Nubians

This side the Nile, who other laws obey,

Arabs (both men and steeds), Macrobians,

A wealthy race, who’ll make a fine array,

Chaldeans also and Iranians,

And many more I hold beneath my sway,

To wage such war on Nubia that soon

From Africa – your land – they will be gone.’

51

King Agramante thought this second scheme

Of King Gradasso’s opportune and sound,

And he blessed Fortune, who had driven him

On this deserted island thus aground;

But his first proposition did not seem

Acceptable on any terms; he found

(Even to save Biserta) such a plan

His honour would irrevocably stain.

52

‘If Count Orlando challenged is to be,’

The king replied, ‘that combat is my due,

And I am ready; let God deal with me

As He thinks fit.’ ‘My plan let us pursue,’

Gradasso said, ‘and in conformity

With what you deem appropriate to you.

I have just thought of this : let us both fight

The Count, and let him bring another knight.’

53

‘If I am not left out, I’ll not complain,

And whether first or second, I don’t mind,’

The other said; ‘a comrade in such vein

As you in all the world I could not find.’

Sobrino cried, ‘And where do I remain?

If I seem old to you, let me remind

You that I have the more experience.

In danger, strength has need of common sense.’

54

Sobrino, though not young, is still robust,

And famous for his feats of arms; he says

That to his vigour they can safely trust –

He feels as strong as in his salad days.

Sobrino’s claim is recognized as just.

A messenger is sent with no delays

To Africa: the challenge of the three

Delivered to the Count by him shall be.

55

If he accepts, he and two knights shall make

For Lampedusa (a small island, this,

Set in the self-same sea); and they shall take

Their armour and all such necessities

For the encounter; the envoy does not slack

The speed of oars and sail until he sees

Biserta; there he finds the paladin

Awarding spoils and captives to his men.

56

The messenger the challenge of the three

Made known, causing Orlando such delight

That gifts with ample generosity

He showered on the envoy, left and right;

For in the meantime from his comrades he

Had learned that King Gradasso (by no right)

Was girt with Durindana, for which blade

A journey to the East he would have made;

57

For he believed Gradasso to be there,

Since he had heard the king had gone from France.

Now, in a place not far away, but near,

Fate offered him this unexpected chance.

Almonte’s horn, so resonant and clear,

And Brigliadoro, too, no less, he wants.

And both of these, Orlando has long known,

Are in the hands of King Troiano’s son.

58

He chose as comrades in this triple test

His brother Oliver and Brandimart.

He knew their expertise was of the best

And that they truly loved him from the heart.

Then of good destriers he went in quest,

Good weapons, armour good in every part,

Not for himself alone, but for all three.

(You will recall why this was necessary.)

59

Orlando (as I many times have said)

Scattered his arms in madness all around.

The other two their armour had to shed

When captives of the Sarzan they were bound.

Of the best weapons Agramante bled

His kingdom for the war; thus few are found

And even those few lack the qualities

Which worthy are of heroes such as these.

60

Such armour as there is, inferior,

Rusty and tarnished, Count Orlando takes

And with his comrades goes towards the shore

And plans for the ensuing combat makes.

When they have gone about three miles or more

The sea’s horizon with his gaze he rakes,

And spies a vessel with her sails full-spread

Which for the coast of Africa is sped.

61

No seamen are on board, no pilot steers;

Impelled by wind and Destiny alone,

Her canvas billowing, the vessel nears

The coast and to a beach is carried on.

But now the love I bear Ruggiero veers

Towards his story and I must be gone

To Arles, where with the valiant Clairmont knight

Unwillingly he fought a bitter fight.

62

The warriors their combat had suspended,

For, as I said, the truce, which had been sworn

By both the king and Emperor, was ended

And bitter conflict once again was born;

And which of the two monarchs had offended,

Holding his solemn pledges thus in scorn,

Ruggiero and Rinaldo strive to know

From those who pass before them to and fro.

63

Meanwhile a squire who served Ruggiero well,

A faithful lad, quick-witted and astute,

Who in the tumult, fierce and terrible,

Which now arose, his lord (who was on foot)

Had never lost from sight, but marked him still,

Brought him his horse and sword; but the pursuit

Of battle for Ruggiero holds no charms,

Though he remounts and with his blade rearms.

64

Then he departs, but first he promises

To keep the vow which earlier he swore,

That if he finds his Agramante is

The culprit he will never serve him more,

But leave him and his vile accomplices;

And he performs no further feats of war,

Seeking that day only to ascertain

Who broke the pact: his king, or Charlemagne?

65

He hears the same report on every hand:

King Agramante broke his promise first.

Ruggiero loves him (you must understand);

He sees the pagans broken and dispersed,

And to deny the help of his good brand

When Fortune’s wheel their fate has thus reversed

Would be a grievous error, he thinks now,

And he is less inclined to keep his vow.

66

Conflicting thoughts within his mind discourse:

Should he remain or follow Agramant?

Love of his lady rides him like a horse:

To Africa? The bit is adamant.

His head is twisted to another course.

By spurs and menaces of punishment,

He is reminded of the pledge he made

With Montalbano, which must be obeyed.

67

And from the other side he’s whipped and spurred

No less by the disquieting concern

That if he now deserts his stricken lord

A coward’s reputation he will earn.

Many will say that he should keep his word,

But many others that excuse will spurn,

And many more will say that he should break,

Not keep, an oath which it was wrong to make.

68

He meditated all that day and night.

The next day too he pondered, quite alone.

Which of these two decisions would be right:

To stay, or follow where his lord had flown

And bring assistance to him in his plight?

At last the cause of Agramante won.

Love of his bride was strong, and of her beauty,

But stronger still his honour and his duty.

69

He rides to Arles, in hope that he will find

The fleet to take him back to Africa,

But not one vessel has been left behind,

The only Saracens all dead men are;

And Agramante to the flames consigned

The ships he did not salvage from the war.

Ruggiero, since his first decision fails,

Proceeds along the coast towards Marseilles.

70

He’ll seize some vessel (such is now his plan)

And make the pilot carry him across.

But there was the armada of the Dane,

With captured ships (in all a grievous loss

To the barbarians); and not one grain

Of millet in the water could you toss,

So crowded were the ships at anchor there,

Which crammed with conquerors and captives were.

71

Such pagan ships as were not burned that night,

Or sunk, save for those two or three which fled,

Dudone added to his fleet, by right,

And to Marseilles in convoy safely led.

And seven kings, acknowledging their plight,

To the inevitable bowed their head,

Their seven ships surrendered to the foe,

And silent stood, cast down and full of woe.

72

The Dane had disembarked some time before:

His aim had been to visit Charles that day.

Long lines of captives and a splendid store

Of spoils formed a spectacular array.

The prisoners were marshalled on the shore.

Around them, jubilant, as is the way

Of victors, Nubians on high proclaim,

And Echo’s voice resounds, Dudone’s name.

73

Ruggiero hoped, while riding from afar,

And to confirm this hope he pricked his steed,

This was the missing fleet of Africa;

But drawing near, he recognized instead

The king of Nasamona, prisoner,

With Baliverzo, Agricalte, led

In chains with Manilard and Farurant,

Who with Clarindo wept and Rimedont.

74

Ruggiero’s love was such, he grieved to see

How much they suffered in their wretchedness.

He knows it will be sheer futility

To plead with empty hands; to gain redress

He must use force. Couching his weapon, he

Attacks the guard: a hundred men, no less,

Are lying on the ground and not by chance,

Struck either by his sword or by his lance.

75

Dudone hears the uproar and looks round:

The spectacle of fleeing men he sees,

The havoc and the slaughter on the ground,

But has no notion who Ruggiero is.

Calling for shield and helmet, with one bound

He leaps upon the destrier with ease

(Though wearing armour), as befits a peer

And paladin who means to use his spear.

76

He shouts commands for all to clear the way

And of his spurs he makes his steed aware.

In prisoners who saw Ruggiero slay

A hundred more, the signs of hope appear.

Seeing Dudone come with no delay

Alone on horseback (all the others were

On foot), he judged him leader of that host:

To fight with him was what he wanted most.

77

Though in mid-course, the Dane, when he discerned

That his opponent was without a lance,

His own flung far away; for he’d have spurned

To benefit from such a circumstance.

Ruggiero by this courteous gesture learned

This was a noble paladin of France,

And to himself he said, ‘I know him by

Such chivalry; this he cannot deny.

78

‘I will entreat him to reveal his name,

If he is willing, ere we come to blows.’

And so he did, and he achieved his aim

And learned that he the son of Ugier was.

Dudone asks Ruggier to do the same

And in return he pays the debt he owes.

Each having told his name, each next proceeds

To challenges and then from words to deeds.

79

Dudone had that iron club which brought

Him lasting honour in a thousand fights,

And with it demonstrated as he fought

He was the scion of brave Danish knights.

The sword (no better sword was ever wrought),

Which opens every breastplate that it smites

And every helm, allowed the Dane to test

Ruggiero’s skill and valour at their best.

80

But in his deep concern to spare his bride

Whatever pain and suffering he could

(As out of love for her he always tried),

And, knowing if he shed Dudone’s blood,

This would offend her – on her mother’s side

(His knowledge of the House of France was good)

She was his cousin in the first degree,

Both of two sisters being the progeny –

81

He never used the point against his foe

And rarely used the edge; where the club fell

He stepped aside or warded off the blow.

Turpin believes (and I believe as well)

Ruggiero could have laid Dudone low

With a few strokes; but, he goes on to tell,

Although the Dane was many times exposed,

Only the flat of Balisard was used;

82

For he could use the flat of it just like

The edge, so sturdy was its tempering.

Repeatedly the blade descends to strike

The Dane in a strange game of ring-a-ding,

Producing stars Dudone does not like,

For he can scarcely to his saddle cling.

But you will all the more enjoy my chime

If I defer it to another time.

CANTO XLI

1

A perfume clinging to the lustrous hair

Or silky beard or dainty raiment of

A youth or maiden, exquisite and fair,

Which often wakens tearful thoughts of love,

Releasing a new sweetness on the air

Which lasts for many days, will clearly prove

By manifest, convincing evidence

Its pristine and unchanging excellence.

2

That heavenly liquid which Icarius

Rashly induced his harvesters to taste

(Which lured, they say, the Celtic tribes to cross

The Alps, heedless of hardships to be faced),

At the year’s end retains, matured, for us

The sweetness of the grapes when they were pressed.

Leaves on a tree in winter show how green

The foliage in spring-time must have been.

3

That famous House, whose glory long has shone,

Illustrious in deeds of chivalry,

Whose splendour, still increasing, yields to none,

Clearly proclaims this truth with certainty:

The line of the Estensi springs from one

Who in all ways by which a man can be

Uplifted rose to a celestial height

And like the sun irradiated light.

4

Ruggiero, who in every worthy deed

The honour of a valiant cavalier

And signs of magnanimity displayed

Which lately ever more apparent were,

Dissembled with Dudone, as I said.

Mercy it was which caused him to forbear;

How strong in truth he was he would not show,

Lest he should deal the Dane a mortal blow.

5

Dudone knew for certain how things stood.

Ruggiero had no wish to take his life:

He left so many chances unpursued,

As when Dudone wearied in the strife

Or failed to keep his guard; he understood

That this was an affair of honour. If

Ruggiero in the combat came off best,

He would not yield in chivalry at least.

6

‘In God’s name, sir,’ he said, ‘let us make peace,

For I have lost all hope of victory

I have no hope of winning, I confess

And I surrender to your courtesy.’

Ruggiero answered, ‘I desire no less

To call a halt, but this the pact shall be

You must consign to me these seven kings,

Freed from their bonds and from their sufferings.1

7

Ruggiero pointed to the seven, who

In fetters stood dejected, as I said.

With them to Africa he means to go,

And nothing their departure shall impede.

The paladin makes no objection to

Ruggiero’s terms: the seven kings are freed.

He lets them choose the vessel which seems best

And so for Africa they sail in haste.

8

The ship’s mast bears its canvas spreading white,

Each bellying to the treacherous wind in turn.

At first this fills the pilot with delight

As straight upon her course the ship is borne

The shore recedes and soon is lost to sight,

As though the sea were bounded by no bourne.

The wind, as darkness fell, its treachery

Made clear as day for all on board to see.

9

From blowing dead astern, it veers to cross

Their bows, then gusts head-on; and shifts again

To whirl the vessel round; at hopeless loss

The seamen try to sail her, but in vain.

From all four quarters towering breakers toss;

No curb the foaming seas can now restrain.

The travellers look on in awe and dread,

And with each threatening wave they think they’re dead.

10

Now from the poop, now from the prow, a blast

Impelled the vessel on, then in reverse;

Over her bulwarks yet another passed

The threat of shipwreck at each gust grew worse

The helmsman, sicklied with the pallid cas

Of terror, sighed, or shouted himself hoarse

Or signalled with his hand, time and again,

To swing or drop the yard but all in vain.

11

His shouts, his signals are of no avail:

The rain, the dark have blotted him from sight

And noises louder than his words assail

The air as voices of the crew unite

To mourn their fate in a concerted wail,

While crashing waves together join their might.

To port, to starboard, at the stem or stern,

Not one command could any man discern.

12

The wind in fury screeches through the spars.

Flash after flash of lightning streaks the sky

Clap after clap of thunder rolls and roars.

All their accustomed skills the sailors try:

Some hurry to the helm, some to the oars;

While some the rigging loosen, others tie

Some bail the water out, repeatedly

The sea repouring back into the sea.

13

Boreas in a frenzy castigates

The raging storm which, shrieking louder still,

The sails against the mainmast flagellates.

The water rises up almost until

It laps the sky; the rowers at their seats

Grasp broken oars and at the tempest’s will

The vessel, unresisting, veers her prow,

Her bulwarks to the waves exposing now.

14

The starboard gunwale dips beneath the flood,

Threatening to turn the vessel upside-down,

And all on board commend their souls to God,

Now more than ever sure that they will drown.

The blows of Fortune with no interlude

Disaster with yet more disaster crown.

The ship in many parts is gaping wide,

And hostile water rushes through inside.

15

From every quarter now the tempest wreaks

An onslaught yet more dire and terrible.

Sometimes the sea mounts up as though it seeks

The highest circle where the Angels dwell;

Sometimes it lifts them to such lofty peaks

That looking down they see the depths of Hell.

They have no comfort now in hope or faith.

Before them looms, inevitable, Death.

16

All night across a turgid sea they speed,

Now here, now there, as drives the changing wind.

It should have dropped by day-break, but instead

It blows again, more dangerously inclined.

And now they see a naked rock ahead.

Towards it willy-nilly, howling blind,

The tempest, still reluctant to relent,

Carries them angrily, malevolent.

17

The helmsman, pale with terror, tries to force

The tiller round in a vain hope to steer

The ship along another, safer course;

But far away the mocking waters bear

The broken rudder, while with no remorse

The wind so fills the sails, no time is there

To lower them, or orders seek afresh;

At any moment now the ship will crash.

18

When it is seen that nothing can be done

To save the ship from her impending fate,

Then every man looks after number one.

Concerned for their own lives, they do not wait,

But scramble down into the boat; and soon

So burdened it becomes beneath their weight,

It threatens to surrender to the wave

And drown all those whom it was meant to save.

19

Seeing the captain, bos’n and all hands

Desert the vessel without more ado,

Ruggiero, in his tunic as he stands,

Unarmed, decides at once to join them too;

But when he does he quickly understands

The boat will sink beneath the overflow.

As still more people clamber for a place,

It plummets to the depths without a trace.

20

The little lifeboat disappears from sight

With all who left the vessel to her fate

The piteous shrieks they utter in their plight

As help from highest Heaven they entreat,

Are not for long continued, for with spit

The angry sea pours over them in spate,

Choking the larynges from whence emerge

The plaintive cries, soon silenced by the surge,

21

Some sink below, never to reappear,

Some break the surface, bobbing on the waves.

A head, an arm, a leg shoeless and bare,

Are glimpsed as hopefully some swimmer braves

The flood. Ruggiero will not yield to fear;

His body from the sea’s embrace he heaves.

He sees the naked rock not far away,

Where all assumed the ship must crash that day.

22

With arms and legs Ruggiero means to strive

Towards that dry, though rocky, piece of land.

Blowing the waters back, which would deprive

Him of his breath, he battles for the strand.

Meanwhile the raging wind and tempest drive

The empty vessel, left with not a hand

On board, of all whose evil destiny

Led them to seek salvation in the sea.

23

How fallible are the beliefs of men!

The vessel did not perish but sailed on.

Her captain and her crew no hope had seen.

They let her drift, abandoned and alone.

The wind, it seems, its tactics altered then.

Seeing the exodus of everyone,

It steered the ship towards a clear fairway,

Well out to sea where safer waters lay.

24

Though unresponsive to the pilot’s hand,

Once she was free of him she sailed a route

Direct to Africa and came to land

Beyond Biserta, two or three miles out,

On the Egyptian side, and in the sand

She grounded; there Orlando, who set out

With his companions, as I said before,

Was walking and conversing on the shore.

25

He wonders what can be the state of her:

Has she a crew? a cargo? He must know.

With Brandimarte then and Oliver

He takes a skiff and to the ship they go.

She’s empty of all hands; only the destrier

Frontino they discover down below

(He is the only living thing on board),

And find Ruggiero’s armour and his sword.

26

Ruggiero had departed at such speed,

To buckle on his sword there was no time.

The Count knew Balisarda well – indeed

This weapon had belonged to him one time.

I know that the whole story you have read:

How Falerina lost it at the time

Orlando laid her lovely garden waste,

And how Brunello stole it from him next,

27

And to Ruggiero’s keeping gave it then

Near the Carena mountains; just how good

Its tempering, how sharp its edge, had been

From previous experience he could

Well testify on oath (the Count, I mean);

And fervently he offered thanks to God,

For he believed (and later often said)

This was God’s gift for the great task ahead.

28

And a great task it was, for he would fight

With Sericana’s ruler, who he knew

Was a ferociously courageous knight,

Who had Baiard and Durindana too.

He did not prize Ruggiero’s armour quite

As much as those who had good reason to;

He judged it good, but most of all because

So finely-wrought and beautiful it was.

29

Since armour he had little need to wear

(For he could not be wounded, being enchanted),

He gave Ruggiero’s arms to Oliver.

The sword he girded on, for this he wanted.

To Brandimart he gave the destrier.

And so to the companions there was granted

(As he desired, and was his bounden duty)

An equal share and portion of the booty.

30

Each for the day of battle sumptuously

In a new surcoat strove to be attired.

The tower of Babel in embroidery,

Struck by a thunderbolt, the Count required.

A hound his brother’s emblem was to be,

Argent, couchant, unleashed, and he desired

The motto, ‘Till he come’; surcoat all gold

He ordered, as became a knight so bold.

31

By Brandimarte, on that battle morn,

Both for his honour and his father’s sake,

No brightly-coloured garment would be worn;

But a dark surcoat he resolved to take,

Which skilful Fiordiligi would adorn

With bordering as fair as she could make.

When she had done, with many a costly gem

The sombre surcoat glittered at the hem.

32

So fine a surcoat and caparison

His lady makes, in beauty they exceed

The less distinguished armour he has on,

Nobly adorning both the knight and steed;

But from the day this labour was begun

Until it was completed, and indeed

Long afterwards, on Fiordiligi’s face

Of joy, of happiness, there was no trace.

33

A constant dread and torment fill her heart

Lest she may widowed be of her dear knight.

In countless battles he has taken part,

And countless perils faced, yet no such fright,

No terror such as this, nor piercing smart,

So froze her blood, nor turned her deathly white.

Such apprehension, being new to her,

Makes her heart tremble with a double fear.

34

As soon as their equipment they prepare,

The cavaliers hoist sail and put to sea.

Astolfo and Sansonetto, who now share

Command, stay with the army faithfully.

Sweet Fiordiligi’s heart is rent with fear;

Filling high Heaven with many a vow and plea,

She strains her eyes to gaze with all her might

Till out at sea the sails are lost to sight.

35

The duke and Sansonetto were constrained

(Since to cajoling words she paid no heed)

To carry her, resisting, from the strand.

They left her in the palace on her bed,

Distraught and trembling; meanwhile the brave band

Of three by a propitious wind are sped

Directly to the island where a test

Of prowess will conclude the war at last.

36

Orlando stepped ashore, with Oliver

And Brandimart, and on the eastern side

They placed their tent, arriving earlier

Than Agramant, who later occupied

The other end (in this the Christians were

More skilled in strategy). The six decide,

Since it is late and night is drawing on,

Their combat till the morning to postpone.

37

On either side, until the early light,

Armed guards are posted who stand vigilant.

At evening Brandimarte, the black knight,

With the permission of his commandant

(Which he had first requested, as was right),

Approached the foe, to speak with Agramant:

Once they were friends, for with the pagan host

Under their flag from Africa he crossed.

38

When greetings were exchanged and hand clasped hand,

The Christian knight enjoined the pagan king

With many a cogent reason, as a friend,

To take the necessary steps to bring

The combat without bloodshed to an end:

His former cities (to this parleying

Orlando had agreed) he would yet own,

If he would but believe in Mary’s Son.

39

‘Because I loved you deeply and still do,

I give you this advice, my lord,’ said he;

‘I followed it myself, which proves to you

How prudent I consider it to be.

That Christ is God I recognized was true.

A dupe henceforth Mahomet seemed to me.

Salvation’s path I long for you to tread,

And to this truth may all I love be led!

40

‘Your good consists in this in this alone.

No other counsel is of any use

And least of all to fight with Milo’s son.

Greater will be the peril if you lose

Than an benefit which might be won

By victory, or spoil which you might choose.

For if you win, what do you hope to gain?

Whereas defeat will bring you loss and pain.

41

‘What if you kill Orlando here, what then?

Or us, who come resolved to win or die?

Your lost dominions you will not regain;

The state of things will not be changed thereby.

You cannot hope that if we three are slain

Charles will lack men on whom he can rely

To guard the frontiers and to garrison

The outposts and the towers, every one.’

42

Thus the knight spoke, and would have added more,

But he was interrupted by the king,

Whose countenance a proud expression wore,

Whose angry voice was harsh and menacing:

‘For such temerity there is no cure.

None to the madness remedy can bring

Of meddling busybodies who (like you),

Without being asked, tell others what to do.

43

‘That the advice you give me springs from love

Which once you felt for me and still profess

Now that I find you the companion of

Orlando, seems unlikely, I confess.

Rather, that dragon which is wont to rove

In search of souls now holds you in duress

And you desire, as far as I can tell,

To pull the whole world down with you to Hell.

44

‘Whether I lose or win, whether I can

Regain my kingdom, or shall banished be,

The mind of God has settled, which no man

Not I, not you, not Milo’s son, can see.

Whatever is the outcome of His plan,

No craven cowardice will coerce me

To an unkingly act If death were sure,

I’d die ere I my faith and blood forswore.

45

‘And now you may return. if you display

No better prowess in tomorrow’s fight

Than as an orator you showed today,

The help the Count will find in you is slight.’

Fury impels King Agramant to say

These final words inspired by sleen and spite.

Then each returned and rested till the sun

Rose from the sea and morning had begun.

46

The dawn was silvering the sky when al

The combatants had armed and quickly leapt

Upon their steeds. There was no interval

And no dela. Few words were said. Adept

The couched their lances. But, my lord, I shall

Be much at fault if I too long have kept

Ruggiero in the sea and he should drown

While of these others talking I go on.

47

Ruggiero strikes out boldly with each limb

And battles with the overwhelming waves.

The wind and tempest menacing and grim

(But not his troubled conscience), the youth braves.

He fears that Christ is now baptizing him,

Not in that water, clean and pure, which saves,

Which he was slow to seek (by his own fault),

But in this flood so bitter and so salt.

48

And all the many promises he made

To Bradamante now come flooding back,

The pact sworn with Rinaldo and betrayed –

Of all such memories there was no lack.

Four times, ten times, in penitence he said,

If God would overlook these sins so black,

If ever he set foot on land again,

He would become a Christian there and then.

49

Never again would he use sword or lance

Against the Faithful to support the Moor,

But he would straight away return to France

And render service to the Emperor.

No longer would he lead his love a dance

But as a husband honour her, he swore.

O miracle! When he has promised this

His strength and his agility increase.

50

His strength redoubled, and with heart undaunted,

Ruggiero struck the waves and pulled them past

As hard upon each other’s trail they flaunted.

One flung him up, another downward cast.

Now he descended, now again he mounted,

With great distress and labour, till at last

He landed; where the hill most gently verged

Towards the water, dripping he emerged.

51

And all the others who abandoned ship

Are left behind, unequal to the wave.

Alone upon the solitary steep,

Ruggiero, whom it pleases God to save,

Has clambered forth. Though rescued from the deep,

He has another danger now to brave:

Marooned upon this barren rock, he’ll die

Of hunger and privation by and by.

52

Yet with indomitable spirit, ready

To endure what fate the heavens had in store,

Among harsh stones, his progress bold and steady,

He climbed towards the summit; but before

A hundred steps he’d numbered by his tread, he

Saw a man bowed down in years, who bore

The signs of abstinence; his dress, his air,

A hermit worthy of respect declare.

53

When he was close at hand he cried ‘Saul! Saul!

Why do you persecute me?’, in the words

Our Saviour used when he appeared to Paul

Who lay beneath the blow which heavenwards

Would raise him; ‘you have come on a long haul,

Cheating the boatman of his just rewards;

But God has a long arm and reaches you

Just when you think He is least likely to.’

54

The holy hermit had a dream that night

Which God had sent to show how by His aid

Ruggiero would be rescued from his plight

And reach the rock; a vision he then had

Of the past life and future of the knight,

And of his death, how he would be betrayed.

His progeny, his grandsons, God revealed:

All the descendants which his line would yield.

55

The hermit first continued to rebuke

Ruggiero (but consoled him in the end)

For not submitting to the gentle yoke

When Christ had called him to Him as a friend;

That what he spurned in freedom, he now took

With little grace, only prepared to bend

His neck, when he was threatened with a lash

Which, as he feared, upon his back would crash.

56

Then he consoled him: Heaven is not denied

By Christ to any soul who soon or late

In true repentance on His name has cried.

The story he proceeded to relate

About the vineyard labourers who plied

Unequally but equal payment met.

With zeal and love, his steps sedate and slow,

He schools the knight as to his cell they go.

57

Above the hermit’s cell, carved in the stone,

There is a little church which faces east,

Convenient and fair to look upon.

Below, down to the sea, the gaze may rest

On evergreens, a refuge from the sun,

And date-palms offering a fruitful feast.

They are kept verdant by a limpid rill

Which murmurs as it trickles down the hill.

58

And close on forty years it now must be

Since Christ had sent the hermit here to dwell

Where nothing would distract the solitary

From holy contemplation in his cell.

Pure water, fruit or berries from a tree

Sustained his life and kept him strong and well;

Few men were healthier or happier.

He had now entered on his eightieth year.

59

Inside the cell the old man lit a fire

And heaped the table with a choice of fruit;

And when Ruggiero’s clothes and hair were drier

He helped himself and started to recruit.

The hermit led him higher yet and higher

In knowledge of our Faith and in pursuit

Of truth; in the pure water of the spring

Next day the knight received his christening.

60

As to the place, Ruggiero was content

To stay, the more so as the man of God

Had told him formerly of his intent

To send him back in a few days where God

Intended he should be; meanwhile, anent

Such matters as the Kingdom-come of God

They spoke, or of Ruggiero’s own affairs,

Of his posterity and of his heirs.

61

For God, Who knows and sees all things, had shown

The hermit what the future held in store:

That when he was baptized, from that day on

Ruggiero would live seven years, not more

For Pinabello’s death (the deed, though done

By Bradamante, at Ruggiero’s door

Was laid), for Bertolagi’s too, he’d meet

His death in ambush, by Maganzans set.

62

So secret will the treachery remain,

No news of it will spread, nor ever could,

For in the very spot where he is slain

He will be buried by the evil brood.

His wife and sister, that heroic twain,

Will therefore late avenge that turpitude.

His faithful wife, his offspring in her womb,

Will seek him out at last and find his tomb.

63

Between the Brenta and the Àdige,

Below the mountains which so greatly pleased

The Trojan Antenor that willingly

Those sulphur springs by which the sick are eased,

Those fertile fields and smiling meadows, he

Exchanged for Ida, and for the Xanthus ceased

To sigh, for Lake Ascania – her heir

Near Phrygian Este in the woods she’ll bear.

64

In beauty and in valour he will grow,

This new Ruggiero, Bradamante’s joy.

His Trojan origins these Trojans know

Who choose him as the founder of new Troy.

To the defence of Charlemagne he’ll go

Against the Longobards while yet a boy,

And Charles will justly in reward donate

This lovely region as a marquisate.

65

The Emperor will say in Latin: ‘Este

Hic domini’; the gift being thus bestowed,

The name of the fair city will be Este

(Auspicious omen!) and thenceforth exclude

The first two letters of the form Ateste.

And to the anchorite God also showed

The future vengeance, terrible and dire,

Which would be taken for Ruggiero’s sire;

66

For in a vision to his faithful wife

He’d show himself a little before day.

Telling her who it was who took his life,

He’d show the place in which his body lay.

Then with her sister, born and bred for strife,

With fire and flame Pontiero she’d destroy.

And the Maganzans no less cause for tears

Would have when young Ruggiero came of years.

67

Many an Azzo and Obizzo passed

Before Ruggiero’s vision as they spoke,

And many an Albert, till they came at last

To the sublime descendants of these folk,

To Ercole, Alfonso, unsurpassed,

And him to whom I dedicate my book,

And Isabel. Not everything was told:

Silence, the hermit sometimes judged, was gold.

68

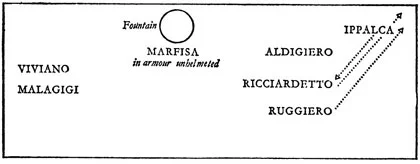

Orlando, Brandimart and Oliver

Meanwhile with lowered lances ride to meet

That Mars of Saracens (thus I prefer

To call Gradasso and the name is fit)

And the two other combatants, who spur

Their destriers, so spirited and fleet.

At more than walking pace they cover ground:

The shore, the sea re-echoes to the sound.

69

At the encounter of three versus three,

In fragments to the sky flew every lance.

The mighty crash was seen to swell the sea,

The mighty crash was even heard in France.

Orlando and Gradasso seem to be

Well-matched, save that Gradasso (not by chance)

Rode on Baiard, which an advantage gave

And made him seem more valorous and brave.

70

Baiardo jolts against the lesser horse,

Taking Orlando also by surprise,

And sends it reeling with the sudden force

From port to starboard, till at last it lies

Full length upon the ground; with hand and spurs

Three or four times in vain Orlando tries

To make it stand; then, grasping sword and shield,

He hastens back on foot to face the field.

71

The king of Africa and Oliver

Had clashed in an equality of blows.

Sobrin was lifted from his destrier

By Brandimarte’s lance, yet no one knows

Which is to blame, the horse or cavalier.

He rarely falls, but this time down he goes

And finds himself – a horseman so renowned –

To his discomfiture, upon the ground.

72

But Brandimarte leaves him where he lies

And turns against the Sericanian;

Seeing Orlando is unhorsed likewise,

He speeds to bring him all the aid he can.

The king and Oliver in the same guise

Proceed, in parity as they began.

Their lances broken on each other’s shields,

A naked blade each brandishes and wields.

73

Seeing Gradasso also disinclined

To press home his advantage (the black knight

Was giving him no chance to change his mind,

But pressed and harried him with all his might),

Orlando turned, and was surprised to find

Sobrino too on foot, with none to fight;

The Count advanced, so menacing and grim,

The heavens trembled at the sight of him.

74

Against the onslaught of so great a man

Sobrino braced himself, alert and tense.

Just as a helmsman in a hurricane

Straight to the raging flood the prow presents,

Holding his course as steady as he can

(Though as the waves mount up his preference

Would be dry land), Sobrino tries to guard

Against the crash of Falerina’s sword.

75

So finely tempered Balisarda is

That plates of armour poor protection are;

And in the hands of such a knight as this,

A knight in all the world unique or rare,

It cuts the shield; nor can it fail or miss,

Despite the rim of steel beyond compare.

It cuts the shield from crown to base all through,

It cuts the shoulder underneath it too.

76

It cut Sobrino’s shoulder; no avail

Against the blade was anything he wore,

No double armour plate, no coat of mail.

The gaping wound was deep and wide and sore.

All his attempts to strike Orlando fail.

The Mover of the heavens granted sure

Defence to Milo’s son from injury:

His body cannot penetrated be.

77

Orlando now redoubles his attack,

Resolved to sever his opponent’s head.

Sobrino knows that valour and draws back

(His shield being useless now, as I have said),

But not in time, for with a mighty crack

The weapon strikes him on the brow. The blade

Descended flat, but smashed the helmet in,

Dazing the wits and senses of Sobrin.

78

He fell beneath the impact of the blow.

For a long time he did not rise again.

The paladin, who sees him thus brought low,

Thinks he is dead and lets him there remain.

His purpose now is with all speed to go

To Brandimarte’s help, lest he be slain.

In steed, arms, sword, perhaps in prowess too,

Gradasso is the stronger of the two.

79

But Brandimarte on Ruggiero’s horse

Acquits himself so well and is so brave,

The other knight, despite his greater force,

Not much of an advantage seems to have.

If, like Gradasso, he had had recourse

To a fine hauberk, strong enough to save

Him from all thrusts, he would have had no need

To step from side to side, as now he did.

80

No horse is more responsive to commands.

When Durindana falls, Frontino leaps

Now here, now there, so well he understands,

And every time a well-judged distance keeps.

The other duel inconclusive stands.

Here neither warrior advantage reaps.

Locked in a parity of strength and skill,

They fight a battle dire and terrible.

81

The son of Milo, who had left his foe

Sobrino on the ground, resolved (I said)

To Brandimarte’s help at once to go.

As he advanced on foot with hurried tread

And was about to strike the king a blow,

He noticed wandering at large the steed

Sobrino had vacated; by the Count

No time was lost in capturing the mount.

82

He seized the horse and, leaping unopposed

Into the saddle, in one hand he held

His sword on high; the other hand was closed

Upon the ornamented reins; he yelled

Gradasso’s name, who, unconcerned, proposed

For all three Christians, when all three were felled,

To make the darkness of the night descend

Before the light of day was at an end.

83

Turning towards the Count from Brandimart,

He aims his weapon straight at the camail.

It pierces everything, the flesh apart:

All efforts to pierce that are doomed to fail.

Then down comes Balisard : no magic art

Against her strokes can anywhere avail.

From helm to shield, from hauberk down to cuish,

She slices all she touches in one swish.

84

In face, in breast, in thigh Gradasso bore

The marks of Balisarda’s swift descent.

His blood has not been shed since first he wore

Those arms, yet by this weapon they are rent,

And not by Durindana (all the more

He’s irked and puzzled by this strange event).

From closer to, or had the length been such,

It would have split him down from head to crutch.

85

The proof is plain: he can no longer trust

His magic arms as he was wont to do.

More thought and greater wariness he must

Employ, and parry more than hitherto.

Since now the Count relieves him of that joust,

Bold Brandimarte stands between the two

Encounters, watching how they both proceed

And ready to assist if there is need.

86

And when the combat to this stage had passed,

Sobrino, who for long had prostrate lain,

Rose to his feet, come to himself at last.

His face and arm were causing him much pain.

He raised his eyes and round about him cast.

He saw his lord fighting with might and main.

With rapid strides, to help him he drew near him,

Moving so quietly that none could hear him.

87

Approaching Oliver, who nothing sees

But Agramant, intent upon the fight,

Sobrino strikes his horse behind the knees,

Which straight away collapses with the knight.

So unforeseen this evil action is

That Oliver, who fails to stay upright,

His left foot from the stirrup cannot free

And lies beneath the horse in jeopardy.

88

A sideways stroke Sobrino tries to deal

To cut his head off – this does not occur:

He is prevented by the shining steel

Which Vulcan tempered and which Hector wore.

Then Brandimarte rushes to reveal

How great a love for Oliver he bore.

He strikes Sobrino down; not long he lies.

The fierce old warrior is quick to rise.

89

He turns to Oliver again, to send

His spirit speeding to the world above;

Or, at the least, the king does not intend

That from beneath that burden he shall move.

But Oliver, despite it, could defend

Himself with his right arm; so well he strove,

Striking and lunging at him with such strength,

He kept Sobrino distant at sword’s length.

90

By warding off Sobrino in this style,

Though still beneath the horse, he hoped and planned

Soon to be extricated from its pile.

The king’s life-blood was crimsoning the sand;

He must accept defeat in a short while.

He was so weak that he could scarcely stand.

Though Oliver had tried repeatedly

To rise, inert the charger seemed to be.

91

The black knight, having turned to Agramant,

Tempestuous assault had now begun,

First at the side of him, and next in front,

His charger whirling as a lathe is spun.

Well-mounted is the son of Monodant,

No less well-mounted is Troiano’s son.

Ruggiero gave him Brigliador to ride

When he had humbled Mandricardo’s pride.

92

The armour which he wears, well-tried and sound,

Confers advantage on the king indeed,

For Brandimart had seized what arms he found

And put them on in haste to meet his need;

But he’ll be donning armour more renowned

(His courage reassures him) with all speed,

Although the king has dealt him such a blow,

, From his right shoulder blood begins to flow;

93

And though Gradasso ave him when the fought

A wound upon the thigh which is no joke.

Watching his moment, Brandimarte caught

King Agramante off his guard and broke

His buckler, wounding his left arm, then sought

And slashed his sword-hand with a glancing stroke.

But this is child’s-play in comparison

With what between the other two went on.

94

Gradasso has disarmed the Count almost.

His helmet at the crown and sides is split.

His shield upon the meadow has been tossed.

His hauberk and his coat of mail are slit

(Though every thrust upon his flesh is lost).

And yet Gradasso had the worst of it:

On face and throat and breast he bears still more

Of Balisarda’s markings than before.

95

Gradasso in his desperation sees,

Though he is drenched in his own blood, that by

So many blows unharmed Orlando is

And that from head to foot he stays quite dry.

His mighty weapon now behold him seize

In both his hands and lift it up on high.

Meaning to split Orlando’s trunk in two,

He brings it down just where he aimed to do.

96

But such a blow is wasted on the Count.

No blood had stained the shining virgin blade,

As if it came down flat or had been blunt.

Yet by its impact stunned, Orlando swayed,

And stars below on earth began to count,

And long it was before he saw them fade.

He dropped the reins – he would have dropped his brand,

But it was chained securely to his hand.

97

The heavy crash had terrified the steed

Which on its back the Count Orlando bore.

Giving a demonstration of its speed,

It raised a cloud of dust along the shore.

The Count, who by the blow seemed atrophied,

Could not control the charger as before.

Gradasso followed hard upon his track:

Of speed Baiardo likewise had no lack.

98

But looking round, he saw King Agramant

Facing the last extremity of man.

In his left hand the son of Monodant

Has grasped the helmet of the African.

He has undone the leather straps in front;

The dagger which he holds reveals his plan.

To Agramante no defence is left

Since even of his sword he is bereft.

99

Gradasso turns; he lets Orlando go;

He rides to bring King Agramante aid.

Incautious Brandimarte does not know;

His eyes, his thoughts, have not an instant strayed

From his intent to give the final blow

And in the pagan’s throat to plunge the blade.

Gradasso has arrived: with all his might,

Both hands upon his sword, he strikes the knight.

100

Father of Heaven, to a martyr’s throne

With Thy Elect, admit this soul, I pray,

Who through life’s stormy voyages has gone

And in the harbour furls his sails today!

Ah Durindana, what a deed was done!

Your cruelty, could no compassion stay?

The truest friend he ever had, or will,

Before Orlando’s very eyes you kill ?

101

His helmet, circled by an iron rim

Two fingers thick, the coif beneath, of steel,

No longer offered a defence to him

Against the blow Gradasso’s sword could deal.

It split them both apart; the world grew dim,

And from his charger Brandimarte fell,

And with the blood which from his head now drained

In widening crimson streaks the sand was veined.

102

Orlando, coming to himself again,

Looks back; and there his Brandimarte lies.

Gradasso’s air of triumph makes it plain

That he is dead; and in him now arise

(I know not which is stronger) rage and pain.

Having no time for weeping, he denies

His grief, and thus his rage the faster flows;

But now at last this canto I must close.

CANTO XLII

1

What curb is there so harsh, what iron bond,

What chain of adamant (if such there be)

To which the force of anger will respond

By keeping to a lawful boundary,

If one to whom your heart by love is joined,

And firmly riveted by constancy,

Is seen to be dishonoured, or to meet

With harm by violence or by deceit?

2

If to a cruel or inhuman deed

Such impetus may drive it on, the soul,

Thus overmastered, an excuse can plead,

Since reason has surrendered its control.

Achilles, when he saw Patroclus bleed,

Dragged Hector’s body round the Trojan wall.

The killing of the killer did not sate him:

He had thus to destroy and desecrate him.

3

Invincible Alfonso, by such fire

Your troops were kindled when the heavy stone

Fell on your brow with injury so dire

That all believed your soul on high had flown.

Then no defences from such blazing ire

Could save your foes, who perished, every one.

No rampart, wall or ditch was of avail,

And not a man was left to tell the tale.

4

The grief it caused your men to see you fall

Moved them to frenzy and to cruelties.

Had you been on your feet, perhaps the toll

Would have been less and the content to seize

And to restore to you the citadel

Of Bastia in fewer hours than days

Which needed were to take it, earlier,

By men of Còrdova and Grànada.

5

Perhaps the avenging Deity permitted

That you should be laid low in that event,

That an excess of cruelty committed

Should meet, as it deserved, with punishment:

When Vestidello in good faith submitted,

Weary and wounded all his spirit spent

Unarmed among the men-at-arms of Spain

(Who mostly served Mahomet) he was slain.

6

But now, to bring this matter to an end,

I tell you that no other wrath is like

The wrath you feel when you see one offend

Your liege lord, kinsman, comrade, or the like;

So it was right that for so dear a friend

A sudden wrath Orlando’s heart should strike

When dead upon the ground he saw him lie,

Felled by the blow Gradasso slew him by.

7

As a Numidian shepherd who has seen

A hateful snake slide off across the sand

When it has left its deadly poison in

His child, will grasp his cudgel in his hand

With rage so now that sword, more sharp and keen

Than any other, Falerina’s brand,

Orlando grasps and turns to do his worst:

His angry gaze meets Agramante first.

8

Bleeding, with half a shield, his helm unstrapped,

Swordless and with more wounds than could be said,

From Brandimarte’s clutch he had escaped,

As from the talons of a hawk, half dead,

A falcon frees itself, for spite uncapped,

Or for some foolish whim unwisely sped.

Orlando reached him: and exactly where

The head and body join, he struck him, there.

9

The neck, being undefended, like a reed

Was severed cleanly with a single slash.

That regal torso, following the head,

Ended its Libyan kingship with a crash,

And to the Acheron its spirit fled,

Where Charon hoisted it aboard. A flash –

And Balisarda, active once again,

Has sought, and found, the Sericanian.

10

When King Gradasso on that fateful shore

Has seen the headless torso fall – dread sight –

A thing occurred, unknown to him before:

His heart within him quailed, his face grew white.

Now, when Orlando down upon him bore,

He seemed to know and almost to invite

His doom, for no defence he made, and no

Attempt to intercept the mortal blow.

11

Gradasso on the right-hand side was cleft

Beneath the lowest rib; the blade went through

His belly and emerged upon the left,

Where it protruded by a palm or two,

Empurpled with his blood from tip to haft.

Thus the best warrior the world e’er knew

Brought to his death a mighty lord than whom

None was more powerful in Pagandom.

12

Small joy Orlando feels at his success

As, leaping with impatience from his steed,

His countenance distorted with distress,

His eyes suffused with tears, he makes all speed

Towards his Brandimart, for whom redress

Has come too late; he sees how he has bled.

He sees the helm as by an axe, split wide:

Frail bark as much protection would provide.

13

Orlando took the helmet from his face

And found that from his forehead to his nose

Gradasso’s sword had left its deadly trace;

Yet breath enough remained in his last throes

To ask for God’s forgiveness and for grace

Before his life descended to its close,

And to exhort the Count to find relief

In patient resignation for his grief.

14

These words he uttered just before the end:

‘Remember me, Orlando, when you pray’;

And he continued, ‘To you I commend

My Fiordi…’ but the ‘ligi’ could not say.

On high, angelic voices sweetly blend

With the celestial instruments which play,

As from the mortal veil his soul, set free,

Is wafted heavenwards in melody.

15

Orlando should feel naught but happiness

At so devout an end; he can believe,

He knows, that Brandimart is now in bliss;

He saw the heavens open to receive

His soul; but human will is weak in this.

At such a loss he cannot help but grieve,

At such a loss the tears pour down his face,

A loss no brother even could replace.

16

Sobrino’s face and side were drenched with gore.

Some time ago he’d fallen helplessly

Upon his back; continuing to pour,

His veins by now must almost empty be.

And Oliver is lying as before,

Pinned by his charger; and whatever he

Contrives, his foot, half-crushed beneath the weight,

And out of joint, he cannot extricate.

17

And if Orlando had not rescued him

(His countenance still sorrowful and wet

With tears), he never could have freed his limb.

The pain is such, he cannot stand, or set

One foot before the other; in this grim

Predicament, while numb and lifeless yet

His whole leg seemed, without Orlando’s aid

No single step could Oliver have made.

18

Small joy Orlando took in victory.

The death of Brandimarte was too high

A price to pay, too harsh a penalty;

And Oliver’s condition made him sigh.

Sobrino’s senses intermittently

Revived and sank, for Erebus was nigh.

So copiously from his wounds he bled,

His life was hanging by the merest thread.

19

Orlando had him carried to a tent

To have his bleeding gashes stitched with care

And spoke some words of kind encouragement,

As if two relatives, not foes, they were.

He felt no rancour after the event.

Humane his actions and benign his air.

Claiming the arms and horses of the dead,

The servants might take all the rest, he said.

20

Here Frederick Fulgoso casts some doubt

Upon my tale and wonders if it’s true.

When with his fleet he journeyed round about

The coast of Barbary, this isle he knew:

He landed and explored it all throughout.

He found it mountainous and, in his view,

On all that rough and rocky piece of land

No-one, no single foot, could level stand.

21

And on that crag (he says) six cavaliers,

The flower of the world though they might be,

Could not have run and jousted with their spears.

To this objection which he puts to me

I answer: at that time (so it appears)

There was a space for tilting, near the sea;

But it was covered when a pinnacle

Of massive rock, dislodged by earthquake, fell.

22

So, bright Fulgosan splendour, brilliant gleam,

Serene refulgence which for ever glows,

If in the presence, it may be, of him

To whom your land its peace and safety owes,

You have declared that I untruthful seem,

Let us our difference in friendship close:

Do not be slow in telling him that I

Perhaps as elsewhere in this do not lie.

23

Orlando, gazing out to sea meanwhile,

Noticed a little craft, its sails full-spread,

Making, it seemed to him, straight for the isle

As with all haste before the wind it sped.

But who it was approaching in this style

I will not tell you now; let us, instead,

Return to France, where they have chased away

The Moors, and see if they are sad or gay.

24

And let us see how fares that constant Maid

Who sees her only joy depart again.

I speak of Bradamant, who is dismayed

When she discovers that the vow is var

Which a few days ago Ruggiero made

In earshot of the troops of Charlemagne

And Agramant; and if in this he fails,

Her heart, bereft of hope, within her quails.

25

Then, newly giving vent to her distress,

Repeating her by now familiar wails,

Calling Ruggiero cruel, pitiless,

To the full blast of woe she spreads her sails

And in an anguished voice with bitterness

Against high Heaven itself she rants and rails,

Calling it weak, unjust and impotent,

Since perjury receives no punishment.

26

She turned against Melissa in her grief,

The grotto and the oracle she cursed,

To which she has accorded such belief,

She’ll perish in the sea of love immersed.

She turned next to Marfisa for relief;

Her mounting frenzy rising to its worst,

She cried and shrieked and endless clamour made

And on her kindness threw herself for aid.

27

Marfisa shrugs; what little she can say

To comfort her,she says; she has no doubt

Ruggiero will return to her straightway

And claim her as his bride; if he does not,

Marfisa will not let him get away

(She gives her solemn word) with such a blot

On his escutcheon (which is hers as well) :

Fulfilment of his vows she will compel.

28

And thus she helps the Maid to check her grief

Which, being vented, is less bitter now.

So, having seen and heard her gain relief,

Her love reviling for his broken vow,

Let’s find her brother and discover if

He better fares, although I don’t see how:

In every nerve he is aflame with love –

It is Rinaldo I am speaking of,

29

Rinaldo who so loved, as you recall,

Angelica the beautiful; and yet,

Although her beauty held him now in thrall,

He had been drawn by magic in Love’s net.

The other knights a peaceful interval

Enjoy, after the Saracens’ defeat.

Of all the victors, he alone remains

A captive, bound in sorrow by Love’s chains.

30

A hundred men for news of her he sent.

He too had searched; when no one could succeed,

To Malagigi in the end he went,

Who many times had helped him in his need;

And he confessed to his enamourment,

Standing with downcast brow and blushing red.

He begged him finally to tell him where

He’d find his love, Angelica the fair.

31

Amazement at such love, so strange and new,

Went spinning round in Malagigi’s head.

Rinaldo could have had the girl, he knew,

Had he so wished, a hundred times in bed;

And he himself did all that he could do,

And all that he could find to say, he said.

He threatened and cajoled but nothing moved him.

He did not want her then, although she loved him.

32

And what is more, if he had yielded then

She’d promised to set Malagigi free.

But now what has the sorcerer to gain?

Why should he listen to Rinaldo’s plea?

What of the suffering, what of the pain

Which he endured while in captivity?

In that dark dungeon he might well have died

Because Rinaldo his request denied.

33

But as Rinaldo’s pleas for aid still more

Insistent and importunate appear,

His cousin Malagigi they assure

The love which they betoken is no mere

Caprice; and all the injuries of yore

As in the ocean sink and disappear.

He does not let Rinaldo plead in vain

But now resolves to help him in his pain.

34

Setting a certain time for his return,

He gave Rinaldo hope, and went his way

The fate of fair Angelica to learn:

Was she in France, or was she far away?

Such matters conjured demons could discern.

He reached his secret cave without delay

(To no one else was it accessible)

And summoned droves of spirits by a spell.

35

He chooses one who in affairs of love

Is well informed; he asks, ‘How can it be

Rinaldo’s heart, once hard, which naught could move,

Is now so soft?’ He learns the mystery

Of the two fountains, how the water of

The one enkindles passion; contrary

Effect the other has; no cure is known,

But each is cancelled by the other one.

36

The waters which the heart from loving bar

Rinaldo drank, and harsh and cold became.

No pleadings of the fair Angelica

Availed; but then at last the moment came

When he was led by an unlucky star

To drink the waters which the heart inflame.

His passion now for her is desperate

Whom beyond measure he was wont to hate.

37

An evil star, a cruel fate indeed!

The fever from the icy stream he sips

Just when the fair Angelica is led

To touch the loveless water with her lips.

All soft emotion from her heart is shed;

Henceforth her flesh for him with horror creeps

As for a snake; and he as much loves her

As he abhorred and scorned her earlier.

38