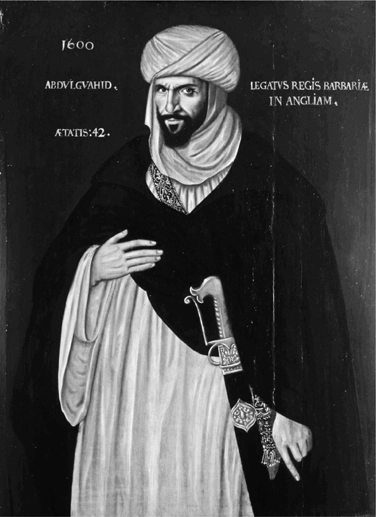

Shakespeare’s company played at court that Christmas, so he may have seen the Barbarian delegation in the flesh. The surviving portrait of the ambassador is perhaps the best image we have of what Shakespeare intended Othello to look like.

Peele’s play mingled historical matter with a more general sense of the barbarian, the other, the devilish—bad Muly Mahamet surrounds himself with demonic and underworld associations. Audiences would have come to The Moor of Venice with the expectation of something similar, but witnessed a remarkable inversion whereby a sophisticated Venetian is the one who comes to be associated with the devil and damnable actions. So evil is Iago’s behavior that at the end of the play, Othello not only calls him a “demi-devil” but half expects him to have the cloven foot of Lucifer.

1. A noble Moor: the Barbary ambassador painted in London, 1600.

Othello is initially referred to (by Rodorigo and Iago) not by his name, but as “him” and then “his Moorship” and then “the Moor.” Depriving someone of their name and referring to them solely in terms of their ethnic origin is a classic form of racism. In Shakespeare’s other Venetian play, something similar happens with “the Jew.” In early modern English, however, the primary usage of the term “Moor” was as a religious, not a racial, identification: Moor meant “Mohammedan,” that is to say Muslim. The word was frequently used as a general term for “not one of us,” non-Christian. To the play’s original audience, the opposite of “the Moor” would have been not “the white man” but “the Christian.”

One of the most striking things about the figure of Othello would accordingly have been that he is a committed Christian. The ground of the play is laid out in the first scene, when Iago trumpets his own military virtues, in contrast to Cassio’s “theoretical” knowledge of the art of war (Cassio comes from Florence, home of such theorists of war as Machiavelli):

And I — of whom his eyes had seen the proof

At Rhodes, at Cyprus and on others’ grounds,

Christened and heathen…

These lines give an immediate sense of confrontation between Christian and heathen dominions, with Rhodes and Cyprus as pressure points. Startlingly, though, the Moor is fighting for the Christians, not the heathens.

Again, consider Othello’s response to the drunken brawl in Cyprus:

Are we turned Turks, and to ourselves do that

Which heaven hath forbid the Ottomites?

For Christian shame, put by this barbarous brawl!

Such Christian language in the mouth of a Moor, a Muslim, is inherently a paradox. It suggests that Othello would have been assumed to be a convert. The “baptism” that Iago says he will cause Othello to renounce would have taken place not at birth but at conversion. The action of the play reconverts Othello from Christianity, through the machinations of Iago. In this sense, it is fitting that Iago appeals to a “Divinity of hell” and that Othello acknowledges at the end of the play that he is bound for damnation.

The notion of conversion was crucial in the Elizabethan perception of the relationship between European Christianity and the Ottoman empire. The phrase to “turn Turk” entered the common lexicon. Islam was as powerful an alien force to Europeans in the sixteenth century as communism was to Americans in the twentieth. To turn Turk was to go over to the other side. It could happen in a number of different ways: some travelers converted by a process of cultural assimilation, others who had been captured and enslaved did so in the belief that they would then be released. It is easy to forget how many English privateers became Ottoman slaves—on one occasion, two thousand wives petitioned King James and Parliament for help in ransoming their husbands from Muslim captivity.

If Shakespeare read all the way through Richard Knolles’ General History of the Turks, one of the books to which he seems to have turned during his preparation for the writing of Othello, he would have learned that once every three years the Turks levied a tax on the Christians living in the Balkans: it took the form of ten to twelve thousand children. They were deported and converted (circumcised), then trained up to become soldiers. They formed a highly feared cadre in the Turkish army known as the Janissaries—there is an elite guard of them in The Battle of Alcazar, while Bajazet’s army in Christopher Marlowe’s Tamburlaine the Great combines “circumcisèd Turks / And warlike bands of Christians renegade.” Othello is a Janissary in reverse: not a Christian turned Muslim fighting against Christians, but a Muslim turned Christian fighting against Muslims. Although the captain-general of the Venetian army was always a “stranger,” conversion in Othello’s direction, from Muslim to Christian, was much rarer than the opposite turn.

The second Elizabethan sense of the word “Moor” was specifically racial and geographical: it referred to a native or inhabitant of Mauretania, a region of north Africa corresponding to parts of present-day Morocco and Algeria. This association is invoked when Iago falsely tells Rodorigo toward the end of the play that Othello “goes into Mauritania and taketh away with him the fair Desdemona.” Ethnic Moors were members of a Muslim people of mixed Berber and Arab descent. In the eighth century they had conquered Spain. This may be the association suggested by Othello’s second weapon, his sword of Spain.

Given that the Spanish empire was England’s great enemy, there would have been a certain ambivalence about the Moors—they may have overthrown Christianity, but at least it was Spanish Catholic Christianity. Philip II’s worst fear was an uprising of the remaining Moors in Granada synchronized with a Turkish invasion, just as Elizabeth I’s worst fear was an uprising of the Irish synchronized with a Spanish invasion. As it was, the Turks took a different turn: in 1570, shortly after the end of the Morisco uprising and Philip’s ethnic cleansing of Granada, they attacked Cyprus.

The alliance of European Christians against the Ottomans was uneasy because of post-Reformation divisions in Europe itself. Independent lesser powers such as Venice and England found themselves negotiating for footholds in the Mediterranean theater. Hence the diplomatic maneuvering that brought the Barbary ambassadors to London—and hence also the blow to Venice caused by the loss of Cyprus in 1571. Shakespeare changes history. He sees off the Turk and implies instead that the real danger to the isle comes from the internal collapse of civil society.

1 comment